Pepperell’s purposeful oddity

Those who research in Massachusetts records are used to seeing it.

Prior to a marriage in that colony and Commonwealth, the parties had to give advance public notice of their intention to marry either in their churches or by posting it in some public place over a period of some days.

In some jurisdictions, these were called banns, sometimes spelled bans, and the technical definition of “bans of matrimony” was: “A public announcement of an intended marriage, required by the English law to be made in a church or chapel, during service, on three consecutive Sundays before the marriage is celebrated. The object is to afford an opportunity for any person to interpose an objection if he knows of any impediment or other just cause why the marriage should not take place.”1

In some jurisdictions, these were called banns, sometimes spelled bans, and the technical definition of “bans of matrimony” was: “A public announcement of an intended marriage, required by the English law to be made in a church or chapel, during service, on three consecutive Sundays before the marriage is celebrated. The object is to afford an opportunity for any person to interpose an objection if he knows of any impediment or other just cause why the marriage should not take place.”1

That was certainly the practice followed in early Massachusetts. The law as far back as 1692 provided that a justice of the peace or minister there could solemnize a marriage “being likewise first published by asking their banns at three several publick meetings in both the towns where such parties respectively dwell, or by posting up their names and intention at some publick place in each of the said towns, fairly written, there to stand by the space of fourteen days, and producing certificate of such publishment under the hand of the town clerk or constable of such towns respectively.”2

This continued to be the law there after the Revolution and the adoption of the first state Constitution:

And be it further enacted by the authority aforesaid, That all persons desiring to be joined in marriage shall have such their intentions published at three public religious meetings, on different days, at three days’ distance exclusively at least from each other, in the town or district, wherein they respectively dwell, or shall have their intentions of marriage posted up by the Clerk of such town or district, by the space of fourteen days, in some public place, within the same town or district, fairly written, and shall also produce to the Justice or Minister, who shall be desired to marry them, a certificate of such publishment, under the hand of the Clerk of such town or district respectively…3

So, all over the town records of Massachusetts, all through published family histories, you see reference after reference to the intention, or intent, to marry.

Except not always.

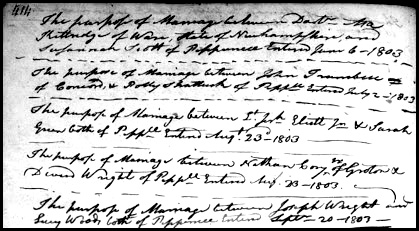

And that had reader Kate Eakman just a little puzzled. She was researching in the records of the Town of Pepperell, County of Middlesex, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, in the early 1800s, and record after record after record carefully noted the “purpose of marriage” between the couples named, rather than the “intention of marriage” recorded elsewhere.4

And so, she asks, “Am I correct that this is a registration of an intent to marry, or am I way off base here?”

The Legal Genealogist respectfully submits that Kate is absolutely correct: this is an intent to marry, and further respectfully submits that the technical legal term for this particular usage in this volume at this time is “a clerk’s quirk.”

The law at the time hadn’t changed. The terminology of the statute in Massachusetts still spoke of an “intention” to marry. But from the early 1800s all through the 1830s, in this one town, the clerks used the terminology “purpose of marriage” instead.5

Eventually, the language changed even in Pepperell: in that same volume of records, some years later, in a different handwriting, you will see “intentions of marriage” recorded, one after the other.6

In these records, where there are records of a purpose of marriage, there are no records of an intention of marriage — and the reverse is also true.

So the two are the same… and (dare we say it) the purpose and intention of the records are identical.

SOURCES

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 120, “bans of matrimony.” ↩

- “AN ACT for the Orderly Consummating of Marriages,” Chapter 25, Laws of 1692-93, in Acts and Resolves passed by the General Court of Massachusetts (Boston: Secretary of the Commonwealth, 1839-); digital images, Massachusetts State Library, DSpace (http://archives.lib.state.ma.us/discover : accessed 19 June 2016). ↩

- “An Act for the orderly Solemnization of Marriages,” 12 June 1786, in The Perpetual Laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, from … 1780 to … 1800…, 3 vols. (Boston: I. Thomas & E.T. Andrews, 1801), I: 321; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 19 June 2016). ↩

- See, e.g., Town of Pepperell, Births, Marriages, Deaths, Intentions, Book B: 414-415; digital images, “Massachusetts, Town Clerk, Vital and Town Records, 1626-2001,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 19 June 2016). ↩

- See ibid., Book B: 414-469. ↩

- See ibid., Book B: 368-370. ↩

I see purpose of marriage quite a bit in the town records. I’ve been fortunate in the case of most of my ancestors (but not in all cases), I have both the purpose, and a few pages later, the actual marriage record in the same volume. Further more, sometimes I find the same record in a different volume with a different clerk handwriting.

The terms are clearly interchangeable.

Hi Judy,

I wrote to you about 6 months ago with regards to a British court case regarding a baronetcy. DNA testing had discovered that a previous baronet was illegitimate and that the title should have belonged to a different man. The court case was about whether the DNA was admissable to change the line of the title and whether consent was properly obtained.

The judgement is now out: https://www.jcpc.uk/cases/docs/jcpc-2015-0079-judgment.pdf

Best Wishes

Gareth Nelson

Thank you Kate and Judy! My great grandparents lived in Pittsfield, Mass, but married in Columbia Co, NY, just across the border. I had thought that maybe NY or Columbia Co. were Gretna Greens but now I think I know why they chose to marry across the border. Gr Grampa was of French Canadian descent and Gr Gramma was Irish and they married in 1890–not a popular time to be Irish. They probably wanted to avoid family intervention. Sadly, 22 years later when Gr Gramma died, the two remaining children (my gramma, 14, and her sister, 11) were placed in Brightside Orphanage on Christmas Eve rather than be taken in and cared for by either side of the family.