Telling the deeds apart

Reader Francine Crowley is having some trouble figuring out what kind of deed a particular document is based on the language in the deed.

“Where could I find more information that will help me determine what type of deed I am looking at based on verbiage it contains?,” she asked, thinking of course of quitclaim, warranty, and grant.

So… let’s first define terms here.

A deed is a “sealed instrument, containing a contract or covenant, delivered by the party to be bound thereby, and accepted by the party to whom the contract or covenant runs.”1

A deed is a “sealed instrument, containing a contract or covenant, delivered by the party to be bound thereby, and accepted by the party to whom the contract or covenant runs.”1

Yeah, right. Sure it is.

It’s a lot more useful to look at its “ordinary modern meaning”: “a written agreement, signed, sealed, and delivered, by which one person conveys land, tenements, or hereditaments to another.”2

In plain English, a deed is the written document by which one person usually transfers ownership of land to someone else.

But there are three basic types of deeds, and that’s what Francine is struggling with.

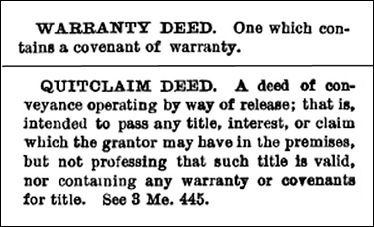

The one we see most often in ordinary land transactions we come across in genealogy is a warranty deed. That’s defined, simply, as a deed “which contains a covenant of warranty.”3 And that, in turn, is a “real covenant by the grantor of lands, for himself and his heirs, to warrant and defend the title and possession of the estate granted, to the grantee and his heirs…”4

The usual language you’ll see in a warranty deed is some language where the seller says, in legal terms, that he really does own this property, free and clear, and will defend the buyer’s right to it if it’s ever challenged down the road.

These representations are called covenants of title and they’re usually set out specifically in the deed.5

Now there will be times when the deed is simply labeled as a warranty deed or general warranty deed, and that label by itself carries with it the promise that the seller actually owns the title to the land he’s selling, free and clear, and will defend it against any claims by anybody else.

But the warranty deed isn’t the only kind of deed you’ll see. Today’s modern residential real estate sales often use what’s called a grant deed, or deed of grant. That’s a “deed to real estate containing an implied promise that the person transferring the property actually has good title and that the property is not encumbered in any way, except as described in the deed.”6

The key difference between a warranty deed and a grant deed is that the warranty deed includes the promise to defend the buyer’s title to the land if it’s ever challenged down the road, while the grant deed doesn’t have that promise. In both cases, though, the seller is representing that he does have good title to the property. In the grant deed, any encumbrance (any debt against the land or any claim anyone else might have to it) is spelled out in the deed itself.

And, occasionally you’ll also see what’s called a quitclaim deed. That’s a deed “operating by way of release; that is, intended to pass any title, interest, or claim which the grantor may have in the premises, but not professing that such title is valid, nor containing any warranty or covenants for title.”7

Notice the key difference for a quitclaim: it doesn’t have those promises. It simply says, “whatever I have, I give or sell to you.” This is the kind of deed that’s often used in family land transfers, the kind you’ll see, for example, when an estate is settled and all the younger kids are giving up their rights to the oldest brother.

Sometimes — and in fact usually — a quitclaim says it’s a quitclaim. If it doesn’t, then the seller will usually use the term quitclaim in saying what he’s doing with the land (“sell, grant, quitclaim…”).

But the real giveaway that a deed is a quitclaim and not a warranty deed or a grant deed is what isn’t there: you won’t find those covenants; you won’t find that promise to defend the buyer’s title down the road.

So… if the deed says it’s a warranty deed or if it contains a promise to defend the title against any challenges down the road, it’s a warranty deed. If it says the seller has good title but it doesn’t have that promise to defend, it’s likely a grant deed. And if it doesn’t have any promises at all, and simply transfers whatever the seller has, it’s likely a quitclaim.

And the difference genealogically? The warranty or grant deed is more likely to have been used between strangers (ordinary buyers and sellers) and the quitclaim more likely to have been used within a family. That’s not 100%, of course. Lots of family members bought and sold land among themselves by warranty deed. But a quitclaim may suggest some relationship among the people involved; it’s at least worth considering the possibility.

SOURCES

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 343, “deed.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 1235, “warranty deed.” ↩

- Ibid., “warranty.” ↩

- See Judy G. Russell, “Covenants of title,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 17 Dec 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 10 July 2016). ↩

- Wex, Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex : accessed 10 July 2016), “grant deed.” ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law,986, “quitclaim deed.” ↩

Thank you for giving so generously of your time again Judy! This helps tremendously

You’re most welcome — thanks for the great question!

Another use of quit claim, maybe? I’ve found a quit claim being used when a widow gives up her dower right to land so that her deceased husband’s heirs can sell the land they’ve inherited to a non-family member. She gets paid for that, of course.

Same thing, Pat: that’s a family-related transfer, and it’s a transfer of whatever right she has (and a dower right is less than an ownership right, so she can’t make the title promises).

Except the quit claim is to the buyer, a stranger.

Right. But she likely wouldn’t have done it except to allow the family (presumably hers, as well as her late husband’s) to clear the title.

The term “deed” is still used occasionally in a non-real estate sense. For example, if I am going to give some valuable personal papers to a university archive, they will probably want me to supply them with a deed-of-gift clearly establishing in writing that I am conveying ownership (and specifying any restrictions on usage that I want the archive to enforce on my behalf, such as no public access without my estate’s until x number of years after I die.)

I Meant to write, “… such as no public access without my estate’s consent until …”

Ah, great descriptions of warranty, quitclaim and modern grant-type deeds. Thank you.

As you know, other covenants / agreements may also be filed as deeds. Powers of attorney, either general (say, to resolve one’s interest in one or more estates) or specific (to sell a parcel of land, the grantee of the sale not necessarily specified). A promise to convey real or personal property for a consideration not necessarily specified, with a penalty for non-performance of the conveyance (say, a parcel of land in exchange for a son’s 8 months’ future work for the father, or a parcel to be conveyed once the grantor himself received title to it, such as land being purchased in right of settlement, or promised by a third party). These may be called Title Bonds or Bonds for Deed.

Careful attention to wording of instruments is necessary. Mortgages may be filed in a regular Deeds series rather than in records books dedicated to recording mortgages.

Thanks again for the clarifications.

Mechanic’s liens are a good source of data for old houses in the states that record them in deed books.

Thank you for this information. In addition can you explain how a deed of Trust works?

We’ve not found evidence of one ancestor’s 1841 death in Ohio, aside from a flurry of Quitclaim deeds from siblings all around the midwest to the one son who ended up with the family farm. They seemed to denote his death. And farther back around 1800 in East Haddam CT, it was common for a lender to file a quitclaim deed relinquishing any burden on a property after a note had been paid off, even though there was no transfer of ownership.

Great explanation, as always, Judy. I had to learn these terms when I sorted out my parents’ estates. Wish I had had your post then 🙂

Jade makes a great point – at the courthouse up here in Cripple Creek, Colorado, they have a wide variety of instruments that were filed with the County Clerk and Recorder. They are generically referred to as “deeds”. Sometimes they are sorted into separate books and sometimes they are mixed in with the real property deeds.

I have often heard “quitclaim” mispronounced as “quickclaim” among lay people (lay=not informed properly of legal terms relating to real property). As in, “He gave me a quickclaim deed to that property. It’s all mine!” You might run across family members describing how they or an ancestor received title to a piece of property using that word.

Come to think of it, it is sort a “quickie deed”.