The language of the law. Part Latin, part Anglo-Saxon, all confusing.

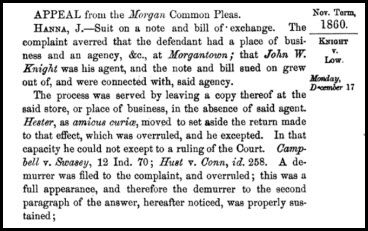

In November of 1860, the Indiana Supreme Court was called on to review a case from the Morgan County Court of Common Pleas.

(You’d never guess, of course, that The Legal Genealogist is heading out to Indiana this weekend, to speak Saturday at the Willard Library in Evansville, now would you? Come on out and join us…)

It seems that the plaintiff in the civil suit said he had a note and a bill of exchange (a written order from A. to B., directing B. to pay to C. a certain sum of money therein named1), that the defendant had a place of business and an agency at Morgantown, that one John Knight was the defendant’s agent, and that “the note and bill grew out of, and were connected with, said agency.”2

It seems that the plaintiff in the civil suit said he had a note and a bill of exchange (a written order from A. to B., directing B. to pay to C. a certain sum of money therein named1), that the defendant had a place of business and an agency at Morgantown, that one John Knight was the defendant’s agent, and that “the note and bill grew out of, and were connected with, said agency.”2

In other words, it was something the agent did or didn’t do that got him sued.

The complaint itself was served on — delivered to — the defendant “by leaving a copy thereof at the said store, or place of business, in the absence of said agent” — and the fact that the agent wasn’t there at the time became one of the two issues in the case.3

First, the defendant answered by saying he wasn’t indebted to the plaintiff. But, second, the defendant said the way the complaint was served didn’t comport with the legal rules. And it was the lawyer for the defendant — one J. S. Hester — who raised that last point.

So the plaintiff came back with a demurrer to the answer. That’s a formal way of saying the answer wasn’t a valid defense. By definition, it’s an “allegation that, even if the facts as stated in the pleading to which objection is taken be true, yet their legal consequences are not such as to put the demurring party to the necessity of answering them or proceeding further with the cause” or an “objection made by one party to his opponent’s pleading, alleging that he ought not to answer it, for some defect in law in the pleading. It admits the facts, and refers the law arising thereon to the court.”4

The trial court agreed with the plaintiff, and judgment was entered against the defendant.

And that’s when the case got really weird.

Because the defendant appealed saying he really didn’t owe the money.

But it was the lawyer — Hester — who said the appeals court should reverse the case because of the issue with serving the complaint.

And, the opinion made clear, on that issue, the Court wasn’t buying it one bit. Because, it explained, on that issue, Hester was acting as amicus curiae.

Say what?

What in the world is that?

It’s a term that shows up time and again in court records that we look at as genealogists, so… here goes.

The dictionary definition of amicus curiae is:

A friend of the court. A by-stander (usually a counsellor) who interposes and volunteers information upon some matter of law in regard to which the judge is doubtful or mistaken, or upon a matter of which the court may take judicial cognizance.

When a judge is doubtful or mistaken in matter of law, a by-stander may inform the court thereof as amicus curiae. Counsel in court frequently act in this capacity when they happen to be in possession of a case which the judge has not seen, or does not at the moment remember.

It is also applied to persons who have no right to appear in a suit, but are allowed to introduce evidence to protect their own interests.5

In other words, it’s somebody who isn’t going to be personally affected by the outcome but who’s invited by the court — or invites himself — to provide information bearing on the decision. Call him (or her) a friendly intervenor.

You’ll see an amicus many times in cases where the issue is one of broad public interest. A civil rights organization may ask to appear as an amicus in a case involving voting rights, for example. Or a business organization may ask to appear as an amicus in a case involving taxes on a business. The group has an interest in the way the case is decided, yes, but it’s not somebody who’s going to be personally affected by the outcome.

And because it’s somebody who isn’t going to be personally affected by the outcome, the amicus isn’t allowed to do all the things that a party — somebody who is going to be personally affected by the outcome — can do.

Most particularly, it’s somebody who isn’t allowed to appeal on the point if the court disagrees with him.

Which is why the Indiana Supreme Court didn’t buy Hester’s argument. Because Hester wasn’t going to be personally affected by the outcome, and didn’t have the right to appeal the issue of whether or not his client had been properly served with the papers in the lawsuit. If that issue was going to be raised, it had to be raised by the client, not by the lawyer.

Gotta love the language of the law…

SOURCES

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 135, “bill of exchange.” ↩

- Knight v. Low, 15 Ind. 374 (1860). ↩

- Ibid., 15 Ind. at 375. ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 353, “demurrer.” See also Judy G. Russell, “The demurrer,” The Legal Genealogist, posted date (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 17 Aug 2016). ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 67, “amicus curiae.” ↩