Getting the stories told

Chicago genealogist Tony Burroughs posted on Facebook this past week that he had signed a Change.org petition to urge that Camp Douglas be placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

“Being a genealogist and historian and knowing the history of Camp Douglas, the Civil War in Chicago and the role of African Americans in the Civil War,” he wrote, “I must sign this petition. I understand the value in getting national recognition. It is an honor to sign.”1

Boy oh boy is The Legal Genealogist ever in on that one.

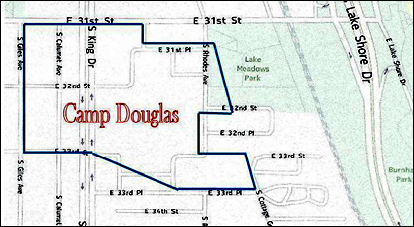

Camp Douglas, for those who aren’t familiar with it, was a military camp in the Chicago area during the Civil War. Originally used as a training camp for Union soldiers, by early 1862 it had been converted to a prison camp to house Confederate prisoners of war.2

Camp Douglas, for those who aren’t familiar with it, was a military camp in the Chicago area during the Civil War. Originally used as a training camp for Union soldiers, by early 1862 it had been converted to a prison camp to house Confederate prisoners of war.2

The story of Camp Douglas needs to be told. First, its story as the training center for tens of thousands of Union soldiers from Illinois, including some of the first African American Union soldiers. Then, its story as the prison camp for as many as 30,000 Confederate soldiers who went through its gates into that prison camp3 … and for the somewhere between 17 and 23 percent of them who died there.4

There are two key criteria for whether a place gets incliuded on the National Register of Historic Places:

• Property associated with events, activities, or developments that were important in the past.

• Property that has the potential to yield information through archaeological investigation about our past.5

Camp Douglas qualifies on both counts.

So I urge you to join Tony and me in supporting the Change.org petition urging that Camp Douglas be placed on the National Register of Historic Places. If you’d like more information, I urge you to check out the website of the Camp Douglas Restoration Foundation.

And, in doing so, I will tell you: for me, this is personal.

I’ve told this story before,6 so forgive me if this is a repeat for you. But — like the story of Camp Douglas itself — these are the kinds of stories that need to be told … and told … and told again…

The story, for my family, is the story of one who was just a boy when he first went off to war. Just 18 years old when he enlisted as a private in Company G of the 25th Regiment of North Carolina State Troops.

He signed up on 20 July 1861 at Asheville,7 not far from his Clay County home,8 and appears on the company rosters through February of 1862.9

Then on 10 March 1862, Sidney Sherman Davenport was discharged at Grahamville, South Carolina.10

The reason given in his discharge papers, dated that 10th of March, was physical disability, but what kind of disability wasn’t stated. In the papers, there’s a wonderfully detailed description:

Sidney S. Davenport a private of Captain W. Grady’s Company (“G”) of the 25 Regiment of NC Vols, born in Cherokee Co in the State of No Car-, aged 18 years, 5 feet, 11 inches high, sallow complexion, Dark eyes, Dark hair, and by occupation a Farmer …11

Sidney was my first cousin four times removed and my second cousin five times removed — our Baker and Davenport lines intertwine more than once. His mother, Dorothy (Baker) Davenport was my third great grand-aunt, younger sister of my third great grandfather Martin Baker. She was born 11 August 1799 in Burke County to David Baker (whose mother was a Davenport) and his second wife Dorothy Wiseman (another Davenport descendant).12

Dorothy married her cousin David Davenport (both a first cousin once removed and a second cousin) sometime around 1817, and records support a conclusion that they had 14 children — 11 sons and three daughters.13

Sidney was the youngest, and you know it must have gladdened his mother’s heart when that youngest boy was sent home from the war that March of 1862. She had to know she couldn’t protect all of her sons with war raging in the land… but she had to have thought, at that moment, that perhaps she could keep that one home.

It was not to be.

Four months to the day after he was mustered out of the 25th North Carolina Regiment for physical disability, Sidney Sherman Davenport joined his older brother Charles and other men from Clay and nearby counties in forming the 62nd North Carolina Infantry Regiment. His rank was recorded as second sergeant, his age as 20.14

And he was off to war once more.

The unit history is mostly unremarkable for more than a year. The men were sent to Johnson City, Tennessee, for training, joined the Army of Kentucky at the end of October 1862, and then sent to guard the railroads until early 1863.15

It must have been a source of some comment within Company B, where Sidney was sergeant over his much older brother Charles. Charles was 16 years older than his baby brother; he was married, and had eight children in his household on the 1860 census.16 Sidney wasn’t much older than Charles’ oldest son. But it must also have been a comfort for Sidney to have his older brother near.

And then came disaster. In August 1863 the 62nd North Carolina was one of the units sent to the defense of the Cumberland Gap in Tennessee. There, they were overwhelmed and on 10 September 1863 taken prisoner when they and the other Confederate troops at the Gap were surrendered by Brig. Gen. John W. Frazier.17

Some 442 soldiers from the 62nd North Carolina — among them both the Davenport brothers — were transferred to what became known as Eighty Acres of Hell — Camp Douglas, the Union prison camp at Chicago, Illinois.18

Charles didn’t make it two months past his arrival at Camp Douglas. His name appears on a list of prisoners forwarded to Camp Douglas from Louisville, Kentucky, dated 24 September 1863. His name is also on an undated roll taken at Camp Douglas in 1863. And it is on the list of those who died between the first and 15th of November 1863.19

Charles died 11 November 1863, of “billious fever” — a generic term used at the time for any illness with fever, vomiting and diarrhea.20 He was buried in grave number 825 at the City Cemetery in Chicago.21

Sidney’s name is also on that September 1863 list of transferred prisoners from Louisville. And records show that he was received at Camp Douglas on 26 September 1863.22

It’s impossible even to imagine how this 20- or 21-year-old boy felt when his older brother died at that prison camp. The conditions there were horrific: twice, public health officials said the camp should be shut down. A year before Sidney found himself at the camp, the president of the U.S. Sanitary Commission — a non-governmental charity — said conditions were so bad that “nothing but fire” could cleanse the camp.23

When the transferred troops arrived in September 1863, more than 4,000 prisoners were at Camp Douglas. By October, there were more than 6,000. There wasn’t enough food, water, clothing or shelter. There wasn’t medicine or medical care to begin to care for all the sick. They were overcrowded, food supplied by subcontractors was poor quality, discipline was harsh.24

But Sidney held on.

He held on through the winter of 1863-64. Through the confiscation of warm coats. Through the blizzard of January 1, 1864 with its -18F temperatures. Through the food shortages that had men eating anything they could find including, reportedly, even rats. Through the overcrowding, the filth, the vermin, the disease.25

He held on through the spring of 1864. Through the summer. Into the fall.26

Maybe he even started believing he would make it home.

It was not to be. On 14 October 1864, Sidney Sherman Davenport died at Camp Douglas. The cause was listed as inflammation of the lungs. He was just 22 years old when he was buried in grave 81, block 2, of the City Cemetery in Chicago.27

All told, David and Dorothy (Baker) Davenport sent six sons into the Confederate Army (Charles, Abner, Josiah, Robert, John and Sidney). Half of them never made it home. When and where Abner died and where he was buried, that remains to be determined.

But Sidney and Charles lie together today with 194 others from the 62nd North Carolina — and with thousands of other Confederates who died at Camp Douglas and whose bodies were later moved to a single mass grave. A pillar stands on Confederate Mound in Oak Woods Cemetery above the grave and the names of those known to have died are inscribed there.

Davenport, C.E., Co. B, 62nd N.C.

Davenport, S.S., Sgt., Co. B, 62nd N.C.28

Rest in peace, cousins. And let us all remember them… and the place where they died.

SOURCES

- Status Update, Tony Burroughs, posted 17 Aug 2016, Facebook.com (https://www.facebook.com/ : accessed 19 Dec 2016). ↩

- See Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Camp Douglas (Chicago),” rev. 20 July 2016. ↩

- “Why Camp Douglas,” Camp Douglas Restoration Foundation (http://www.campdouglas.org/ : accessed 19 Aug 2016). ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Camp Douglas (Chicago),” rev. 20 July 2016. ↩

- “Support Camp Douglas on the National Register of Historic Places,” Camp Douglas Restoration Foundation (http://www.campdouglas.org/ : accessed 19 Aug 2016). ↩

- Judy G. Russell, “Death in Chicago,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 13 Oct 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 19 Aug 2016). ↩

- Sidney S. Davenport, Pvt., Co. G, 25th North Carolina Infantry; Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of North Carolina, microfilm publication M270, roll 315 of 580 rolls (Washington, D.C. : National Archives and Records Service, 1960); digital images, Fold3 (http://www.Fold3.com : accessed 12 Oct 2012), Sidney S. Davenport file, p. 2. ↩

- See 1860 U.S. census, Cherokee County, North Carolina, Shooting Creek, population schedule, p. 168 (penned), dwelling/family 1098, Sidney Debenport in David Debenport household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 10 Apr 2007); citing National Archive microfilm publication M653, roll 892. Shooting Creek was part of the new Clay County formed in 1861. ↩

- Compiled Service Record, Sidney S. Davenport, Co. G, 25th North Carolina Infantry, Fold3 file pp. 2-6. ↩

- Ibid., p. 7. ↩

- Ibid., p. 10. ↩

- Josiah and Julia (McGimsey) Baker Family Bible Records 1749-1912, The New Testament of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ (New York : American Bible Society, 1867), “Births”; privately held by Louise (Baker) Ferguson, Bakersville, NC; photographed for JG Russell, Feb 2003. Mrs. Ferguson, a great granddaughter of Josiah and Julia, inherited the Bible; the earliest entries are believed to be in the handwriting of Josiah or Julia Baker. ↩

- See 1860 U.S. census, Cherokee Co., N.C., Shooting Creek, pop. sched., p. 168 (penned), dwell./fam. 1098, David Debenport household. Also 1850 U.S. census, Cherokee County, North Carolina, population schedule, p. 25 (back) (stamped), dwelling/family 324, David Davenport household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 21 Mar 2007); citing National Archive microfilm publication M432, roll 625. Also 1840 U.S. census, Cherokee County, North Carolina, p. 239 (stamped), David Davenport household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 9 Dec 2002); citing National Archive microfilm publication M704, roll 357. ↩

- Sidney S. Davenport, Sgt., Co. B, 62nd North Carolina Infantry; Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of North Carolina, microfilm publication M270, roll 551 of 580 rolls (Washington, D.C. : National Archives and Records Service, 1960); digital images, Fold3 (http://www.Fold3.com : accessed 12 Oct 2012), Sidney S. Davenport file. ↩

- Marshall Styles, “POW Deaths, 62nd NC Inf Reg, CSA,” USGenWeb (http://files.usgwarchives.net/nc : accessed 12 Oct 2012. ↩

- 1860 U.S. census, Towns County, Georgia, Hiwassee, population schedule, p. 43 (penned), dwelling/family 295, Charles Davenport household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 12 Apr 2007); citing National Archive microfilm publication M653, roll 138. ↩

- Styles, “POW Deaths, 62nd NC Inf Reg, CSA.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Chas E. Davenport, Pvt., Co. B, 62nd North Carolina Infantry; Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of North Carolina, microfilm publication M270, roll 551 of 580 rolls (Washington, D.C. : National Archives and Records Service, 1960); digital images, Fold3 (http://www.Fold3.com : accessed 12 Oct 2012), Chas E. Davenport file. ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “bilious fever,” rev. 13 June 2014. ↩

- Fold3 Chas E. Davenport file, p. 7. ↩

- Sidney S. Davenport, Sgt., Co. B, 62nd North Carolina Infantry; Fold3 file pp. 10-11. ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Camp Douglas (Chicago),” rev. 20 July 2016. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Sidney S. Davenport, Sgt., Co. B, 62nd North Carolina Infantry; Fold3 file pp. 10-11. ↩

- Ibid., p.13. ↩

- Camp Douglas memorial, photographed 2008 by Angela Groenhout (digital copy in possession of jgrussell). ↩

My connection to Camp Douglas is that my second great grandfather, Samuel Sewall Greeley, a Chicago civil engineer, submitted a design for a water and sewer system for the camp. See the blog post here.

I also have a connection to Camp Douglas. My great grandfather, John Thomas Barker, and his brother, William, both served in the 29th Georgia Infantry and were taken prisoners at the Battle of Franklin in December 1864. They were both sent to Camp Douglas. When they were released, they walked home to Georgia.

My grandfather had promised a dying soldier – a Mr. Gray – to take the news of his death to his fiancée – Miss Linia Blake. Not surprising, it wasn’t too long before Miss Blake became Mrs. Barker.

Thanks for passing along the Camp Douglas info. I also want to see it preserved.

OH. MY. GOD. The near-exact same story occurs in my son’s paternal line.

I wrote “Annie WALLEN and the Cumberland Gap: Too Far From Family, Too Close to Home”:

https://digginupgraves.wordpress.com/2015/03/06/annie-wallen-and-the-cumberland-gap-too-far-from-family-too-close-to-home-52-ancestors-2015-9/

And from not far away in NC, either… so sad…

That’s such a sad story about your Davenport cousins, Judy. I recently read some notes written by some Civil War soldiers; and if I remember correctly, one man wrote home that eating rat meat tasted like eating squirrel. I think I also read that some wrote about picking off lice and cooking them. We can’t begin to understand what these brave young men endured.

Yesterday, I received a note from a new-found cousin on Ancestry whose great-grandfather, Wilford Hall, served in the Iowa 8th Infantry during the Civil War. He wrote “His commander was named Geddes. He liked him so much that when my grandfather was born they named him Wadsworth Geddes Hall…hooked that on me as a middle name that I hated most of my life, until I found out the old commander was an okay guy.”

He continued, ” While serving in the Union Army they about starved and ate green corn to survive. They got terribly sick and Wilford’s disability payment was for ‘diarrhea’. He got those payments for nearly a half decade.”

By all accounts, diarrhea was a big killer during the Civil War; and it’s difficult to imagine anything more awful than the terrible living conditions of a camp full men suffering with the vomiting/diarrhea that killed your cousin. May they all rest in peace.

Conditions in all the camps were truly appalling… north and south. Can’t imagine living (and dying) like that.

Hi Judy

Camp Douglas is also where Union regiments that were surrendered to the Confederates at Harpers Ferry were taken including my gggrandfather, Ziba Shippee. I have Ziba’s compiled military record and his entire pension record ($160 from NARA but well worth the expense!). The conditions the Union soldiers were subjected to were as bad as what the Confederates suffered, believe it or not. He and many of the Union soldier’s were housed in old stables at the Illinois State Fair grounds near Camp Douglas because the Camp itself was so full. From what I can tell from Ziba’s records, because of the cold, rainy weather they suffered through in the stables, he became miserably ill and was taken to a hospital. The rest of his life, not only did he suffer from his wounds received at Harper’s Ferry but from the illness (“fever”) he suffered. He was not only physically disable but he was left nearly deaf and blind and suffered from intestinal issues the rest of his life. What the men endured is beyond comprehension and amazes me that any of them lived. It is important that this Camp be made a historical landmark to honor the men who suffered here.

I also recommend reading “To Die in Chicago” if one can find a copy. I was able to get a used copy through Amazon a few years ago and it tells the heartbreaking stories of the men.

My great great grandfather, AAron Spencer Hobbs, was at Camp Douglas when he died. He is buried in the single mass grave in City Cemetary.

Very sad, Bev.

Aaron Spencer Hobbs was my great great great great grandfather.

What about the third Davenport named on that stone, W.H. From Tennessee? Any chance he is somehow related to the other two?

It’s certainly possible — but I don’t have any information about him. He’s not — thank heavens!! — the William who was the brother of Sidney and Charles.

I have a great great Uncle who was an Irish immigrant who died at Camp Douglas. He wasn’t even a citizen! He was at Cumberland Gap when his unit was taken as POW’s. He was buried in the mass grave in City Cemetery also. Such a sad story.

The whole Camp Douglas story is a sad story.

Maybe I missed something in the original posting but why is this being done via a change.org petition and not via the published process for nominations for the National Historic Registry? To get on the national registry, you apply through the appropriate state and it goes up the process to the National Park Service and the National Registry. The Illinois process is outlined here: http://www.illinois.gov/ihpa/Preserve/Pages/Places.aspx

My apologies if I missed that it had been turned down through those channels or something forcing the work-around. Definitely a worthwhile place to have on the National Historic Registry.

The website of the Camp Douglas Restoration Foundation indicates it is in the process of preparing a formal application but is using this process to help it gather public support. This isn’t the usual kind of property that gets included, so it’s looking to broaden awareness and a base of support.

A very fine article. This story deserves to be more widely read, and I have shared it to several Facebook pages and groups, including Camp Douglas Memorial #516, the Chicago Camp of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Bravo!