Rewards for runaways

There was a great discussion on Facebook last week of advertisements for the return of runaways.

In this case, not ads the initial poster was used to seeing — not ads for the return of runaway slaves.

No, these were ads for the return of runaway servants.1

Genealogist Renate Yarborough-Sanders concentrates on African-American research; she notes that “We all know about runaway slave ads, and many of us use them in our research.” But, she said, “here’s something I haven’t seen or thought about before — an ad for a runaway apprentice.”

Genealogist Renate Yarborough-Sanders concentrates on African-American research; she notes that “We all know about runaway slave ads, and many of us use them in our research.” But, she said, “here’s something I haven’t seen or thought about before — an ad for a runaway apprentice.”

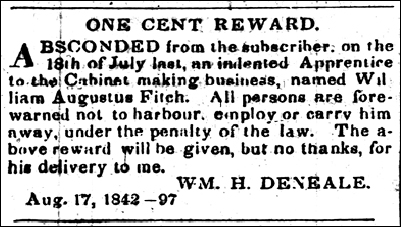

And one ad she had come across is the one you see here: an ad posted in the North State Whig, in Washington, North Carolina, on Wednesday, the 17th of August 1842. William H. Deneale had an “indented Apprentice to the Cabinet making business, named William Augustus Fitch,” who had “absconded.” Deneale offered a one-cent reward, and added: “The above reward will be given, but no thanks, for his delivery to me.”2

And that prompted a question from reader Roberta Estes: “What does the ‘with no thanks’ part mean?”3 Especially when, as Renate noted, “It probably cost more than that to place the ads!”4

Ooooooh… a question for The Legal Genealogist.

Because, of course, the answer lies in the law.

Let’s start with some definitions. Indented Apprentices were servants who entered into legally binding contracts, called indentures, with a master. They were usually youngsters, in their early teen years, and were “usually bound for a term of years, by deed indented or indentures, to serve their masters, and be maintained and instructed by them … This is usually done to persons of trade, in order to learn their art and mystery…”5

So William Deneale in this ad was the carpenter in town, and he’d taken on young Fitch to learn the trade. And Fitch had absconded — run away — made off like a thief in the night.6

Now… it’s pretty clear that if he’s only offering one penny for this young man’s return, and “no thanks” … William Deneale really doesn’t want William Augustus Fitch back at all.

And, in fact, at least one study of advertisements by masters of apprentices opines that, in some cases, the masters “accepted the event and did not want to deal with the likely problems should the apprentice be dragged back to work” and, in others, the masters welcomed it: “For them, having the apprentice steal away one night actually saved the trouble of discharging them. As is true today, employers generally find it easier for the worker to quit on their own behalf than to go through the difficulties of firing them.” Indeed, the study concludes, the ads “offer a wealth of evidence to confirm the argument that a number of masters accepted or even welcomed the departure of apprentices.”7

So why advertise at all?

Because without it masters like Deneale could legally be obligated for damages that apprentices like Fitch caused to others and things that they bought and charged to their masters.

The law generally presumed that a servant was acting on behalf of the master, and therefore the master was answerable for the acts of the servant: “the master may be frequently a loser by the trust reposed in his servant, but never can be a gainer : he may frequently be answerable for his servant’s misbehaviour, but never can shelter himself from punishment by laying the blame on his agent. The reason of this is still uniform and the same ; that the wrong done by the servant is looked upon in law as the wrong of the master himself…”8

Advertising didn’t, and couldn’t, break or end the indenture — that legal contract between master and servant — by itself. But it put the community on notice that the servant wasn’t acting on the master’s behalf, and provided protection for the master if someone else tried to sue for damages caused or debts incurred by the servant.

And, of course, the best part of these ads is… they’re records. Records we can use to add to our family history… records that surely add color and depth to the story.

I mean, seriously… who wouldn’t want proof that “an apprentice boy, by name William Wilson … was 17 years of age last July, and is a stout, well grown lad…”?9 At a time and in a place where proof of age and anything remotely resembling a physical description is hard to find, these ads — and others like them — are pure gold.

SOURCES

- Renate Yarborough-Sanders, status update, posted 7 January 2017, Facebook.com (https://www.facebook.com/ : accessed 10 Jan 2017). ↩

- “One Cent Reward,” North State Whig, Washington, N.C., 17 August 1842, p. 3, col. 1; digital images, Newspapers.com (http://www.newspapers.com : accessed 10 Jan 2017). ↩

- Roberta Estes, comment on Facebook status of Renate Yarborough-Sanders, posted 8 January 2017, Facebook.com (https://www.facebook.com/ : accessed 10 Jan 2017). ↩

- Renate Yarborough-Sanders, ibid., posted 8 January 2017. ↩

- “Of Master and Servant,” William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, Book the First: The Rights of Persons (Oxford, England : Clarendon Press, 1765), 414; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 10 Jan 2017). ↩

- “Abscond; to depart secretly and hide oneself,” Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (http://www.m-w.com : accessed 10 Jan 2017). ↩

- William F. Sullivan, Jr., “‘Born to be Hanged:’ What Runaway Apprentice Advertisements Reveal about Connecticut’s Master Craftsmen in the Early Republic,” 46 Connecticut History 46 (Spring 2007): 1-15; html version, Runaway Connecticut (http://runawayct.org/ : accessed 10 Jan 2017). ↩

- Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, Book the First: The Rights of Persons, 419-420. ↩

- “Ranaway,” Raleigh (N.C.) Register, 30 November 1824, p. 4, col. 3; digital images, Newspapers.com (http://www.newspapers.com : accessed 10 Jan 2017). ↩

Here is an ad I found when I did research at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. French Neutrals were Acadians who had been deported and exiled from their lands in Nova Scotia (Originally Acadia).

May 12, 1768

The Pennsylvania Gazette

FOUR DOLLARS Reward.

RUN away from Richard Clayton, Cordwainer, living in Marcus Hook, Chester county, on the 30th day of April last, an apprentice lad, named JOHN TENDEU, about 18 years of age, 5 feet 5 inches high; he is one of the French Neutrals , and speaks on that dialect, has black hair, is of a dark complexion, and a lover of strong liquor. Had on, when he went away, a grey half worn jacket, an under black and white twilled ditto, blue cloth trowsers, half worn black worsted stockings, shoes almost new, &c. Whoever takes up said apprentice, and secures him in any goal, so that his master may have him again, shall receive the above reward, and reasonable charges, paid by me

RICHARD CLAYTON.

N.B. All masters of vessels are forbid to carry him off at their peril.

That guy definitely wanted his apprentice back!! “Four dollars and reasonable charges” was a lot of money in 1768.

This is fascinating — wonder if it’s applicable in England as well.

There was a recent episode of Who Do You Think You Are when an apprentice absconded at age 15, 5 years into his apprenticeship as a shoemaker, and joined the Royal Marines.

When discovered (presumably because his master sought him out?), he was prosecuted for “Being An Apprentice, For Enlisting and Defrauding His Majesty of 11 Guineas.” He was sentenced to 12 months hard labour. So nobody benefited: the master lost his apprentice, the Marines lost their recruit and the apprentice went to prison.

Yes, the same rules would have applied in England: Blackstone was writing about the English common law, which we here in the US generally incorporated into our laws.

Wow, Judy! Great post, and (believe it or not) I’m most impressed by your citations! Boy, have I got a lot to improve upon in that department!

So, the focus on the word, “indented” really stands out for me, here. I wonder (and I know you’ll tell me) if that is the reason I’d not seen these ads for runaway apprentices before? As I mentioned in the Facebook comments, I’ve spent a lot of time working with apprentice records, because one branch of my family was apprenticed, extensively, in Tyrrell County, NC. I don’t recall if the word indenture was used in the language of the bonds, or not. I’ll have to go back and take a look. (I am pretty sure, though, that at least some of the originals do begin with, “This indenture”.) What I do know, though, is that in the case of all of the apprenticeships I’ve had reason to study, they involved free people of color and/or their base-born children, and were incurred because of NC law. Perhaps, in those cases, runaways were less prevalent. I’ll definitely be revisiting some resourcesto gain a better understanding of the variations in the apprenticeship system!

Thanks for your additional research and for sharing your knowledge and legal expertise with all of us.

Renate

There were essentially TWO system of indentures, Renate: one a voluntary system (these youngsters learning a trade) and the other largely involuntary (youngsters who were bound out because they purportedly didn’t have parents who could care for them). I say “purportedly” there because, as you know, in NC and other states, free children of color were often taken from their parents — involuntarily and often over the parents’ objection — and bound out, particularly in the years just after the Civil War. It was, in essence, a way to keep the children in servitude even if the parents were technically free.

In North Carolina, anyway, there were at least three systems. The involuntary apprenticeship of the children of freedmen, post-Civil War, was a very different creature from the involuntary apprenticeship of free children of color in the antebellum era, which applied to orphaned or “base-born” children. Moreover, based on my studies of indentures in several eastern NC counties (Wayne most closely), there was no real expectation that children were to be taught a trade. In the overwhelming majority of cases, the “trade” designated was farming for boys and sewing for girls. In other words, these children were primarily used as farmhands (often, I found in research for my masters thesis, by relatively young farmers who lacked capital for slaves.)

I’d be very interested to know what your research showed was the difference antebellum and post-Civil War, Lisa — other than, of course, the fact that North Carolina defined all children of former slaves as base born children in order to bind them out immediately after the war.

I liked your explanation of the Master wanting to absolve himself of any harm done by the missing apprentice. I may be confusing the terms Indentured apprentice with indentured servant. I thought I had seen some contracts between a master craftsman and an apprentice’s father where the Master was expecting to benefit from having the apprentice at his beck and call. I got the impression that the apprentice was treated as cheap labor and learning the craft was secondary. I can see where sometimes the Master would hold an apprentice to the original contract and other times, good riddance.

An indentured servant, without more, have have simply been working off a debt (such as the cost of passage from old world to new). An indentured apprentice carries with it a suggestion that this is a youth being trained. Yes, during the years of the apprenticeship, the master was entitled to the youth’s work, but the notion was to get the kid trained in a craft for adulthood. In some cases, a parent would even pay to have the child accepted as an apprentice.

Indentureship problems. I loved this one! Another thing I have found over and over. The “master” abused the indentured child (normally a child) and made life miserable for him. If the master could drive off the child, he would go to the County and say “hey, I know I was supposed to provide this boy with a horse, a new suit of clothing at the end of his indentureship, but he just got up and run away on me. So, I should not have to live up to the contract.” It happened many times and the county usually saw right through it. But, it legally protected him if he went to the officials.

Yes, the legal obligation to pay what were called freedom dues was part of what the master was trying to get out from under.

This is so helpful! I recently ran across a similar advertisement, however in this case, my ancestor was offering “one woodchuck reward”. Probably about the same value as a cent maybe! Thank you so much for your explanation and for making this much less confusing!