Those other land acts

The puzzlement of The Legal Genealogist over the migration of an ancestor from Alabama to Arkansas between 1850 and 1860 led to some research being done by readers, and some suggestions being offered.

And one in particular needs some more attention.

The blog post was published Saturday, and told the story of the apparent move of my fourth great grandfather Boston Shew from Cherokee County, Alabama, to Izard County, Arkansas.1

The blog post was published Saturday, and told the story of the apparent move of my fourth great grandfather Boston Shew from Cherokee County, Alabama, to Izard County, Arkansas.1

And, of course, one question we always have with a move like that is: why? What was the pull of the new area to entice settlers to come there?

In that time period, land — and the availability of land — was certainly a big reason for people to move. And Boston Shew certainly did get a land grant in Arkansas.2

But there was still plenty of land available in Alabama, and dozens and dozens of land grants were issued during the decade of 1850-1860 not just in Alabama but in the county Boston left — and where he left behind some of his adult children (including my third great grandparents).3

So it probably wasn’t land in this case, or at least not land alone.

But in looking at the possibilities, reader Brian Swann noted that there was a development in land around that time that anyone considering the push and pull of ancestral migration ought to consider.

It was the original “Drain the Swamp” effort. The Swamp Acts of 1849-1850.

And the swamp referenced in the acts was literal: the notion was that swamp land would be donated by the federal government to some of the states, including Louisiana, Florida, Arkansas, Indiana and Michigan, and the states could then drain the land, convert it to agricultural use and sell it — paying for the levees and other efforts with the proceeds of the land.4

These lands that were given by the federal government to the states under these statutes were great for cultivation — particularly for cotton — but the issue of flooding was huge. Local authorities argued that reclaiming the land through levees and other flood control efforts would benefit the nation. Congress didn’t finance the flood control efforts directly, but did so indirectly by handing over the lands to the states to sell to finance the levees and other efforts that would protect the lands from flooding.5

So there were other land acts beyond the ones we usually think of — like the Homestead Act — that might have impacted an ancestor and gotten him to go from one place to another.

Which raises the question: how do you know if the Swamp Land Act influenced an ancestor to move to Arkansas?

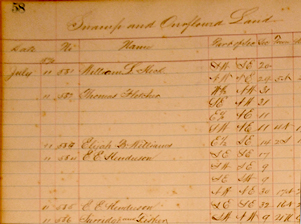

A great resource to look for is the records of the Arkansas Commissioner of State Lands:

• “Patent Books-The patent books are organized in date order from August 1855 through March 2001.”

• “Entry Books-The entry books are organized by Township & Range and can be the most confusing when doing research. …”

• “Governor’s Patents Book B (1855-1860)-Governor’s patents are arranged in date order beginning in August 1855-January 1860. This book serves as a cross reference for the patent and entry books. Governor’s Book A is on loan to the Arkansas History Commission.”

• “Plat Book (North & East)-Unfortunately this is the only existing book of plat maps that accompany swampland patents.”

• “Swamplands Sold-The sales books are listed in sale number order beginning in 1868 coinciding with the creation of the Commissioner of State Lands and Immigration Office.”6

So was Boston drawn by this statute? I don’t think so: his land appears to have been outside of the swamp zone and an ordinary cash sale from the federal government, not swamp land donated by the feds to the state and then drained and sold by the state.

But it’s sure something to keep in mind whenever the question comes up: why did an ancestor move?

Look to the laws… and the land.

SOURCES

- See Judy G. Russell, “An Arkansas mystery,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 18 Mar 2017 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 20 Mar 2017). ↩

- Boston Shew (Izard County, Arkansas), land patent no. 18264, 1 October 1860; “Land

Patent Search,” digital images, General Land Office Records

(http://www.glorecords.blm.gov/PatentSearch/ : accessed 20 Mar 2017). ↩ - See “Land

Patent Search,” digital images, General Land Office Records

(http://www.glorecords.blm.gov/PatentSearch/ : accessed 20 Mar 2017); a search for all patents in Cherokee County between January 1850 and December 1859 resulted in well in excess of 100 grants, including grants to two of Boston’s sons. See Daniel Shew (Cherokee County, Alabama), land patent no. 17317, 1 January 1859; Simon Shew (Cherokee County, Alabama), land patent no. 17318, 1 January 1859. ↩ - See e.g. “An Act to aid the State of Louisiana in draining the Swamp Lands therein,” 9 Stat. 352 (2 Mar 1849); “An Act to enable the State of Arkansas and other States to reclaim the ‘Swamp Lands’ within their limits,” 9 Stat. 519 (28 Sep 1850). ↩

- See Mary C. Suter, “Swamp Land Act of 1850,” Encyclopedia of Arkansas (http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/ : accessed 20 Mar 2017). ↩

- “Swamp Lands (1850),” Historical Documents, Maps & More, Arkansas Commissioner of State Lands (http://history.cosl.org/ : accessed 20 Mar 2017). ↩

Swamp land sales are usually under the Secretary of State for the state of interest. I know Alabama, Arkansas, California, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, Oregon, and Wisconsin were involved.

There were many interesting scandals associated with swamp land sales. Lots of records are there for our research.