Strategy for targeted testing

Time and again, The Legal Genealogist hears the lament: “I don’t have any male in my line to do a YDNA test!” Or, “I don’t have the right person in that line to do an mtDNA test!”

In some cases — many fewer than you might think — those statements may actually be true.

We know, of course, that YDNA is the kind of DNA that only males have and that is passed down from father to son to grandson and so on, largely unchanged through the generations.1 And it’s possible that there really may not be a single living male in the direct paternal line you need (or you might not be able to find one) to do that YDNA test.

And we know that mitochondrial DNA — mtDNA — is the kind of DNA that we all have but that is inherited solely from our mothers, who got theirs from their mothers (our grandmothers) who got theirs from their mothers (our great grandmothers) and so on.2 And it’s possible there too that the person whose mtDNA haplogroup we’d dearly love to identify may not have left a single descendant in that direct maternal line.

But in the vast majority of cases it’s a matter of choosing a different candidate for our testing.

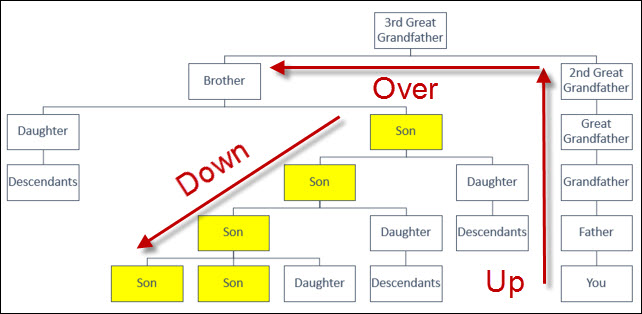

Of looking up, over, and down for the right person to test.

Even when it means looking up and up and up, then over, and then down and down and down for that right person.

Let’s say you really really want to know if your paternal line descends from Niall of the Nine Hostages3; you want that cool badge on your DNA results that says he’s in your paternal line.4 But you’re the one and only child of your father, and you’re female. And he was the one and only child of your grandfather. And he was the one and only child of your great grandfather. So you have no brothers, no cousins, no uncles to test.

You need to look up, over, and down.

Keep going up the generations of your family tree in that line until you find one that didn’t result in a lonely only. Somewhere back in time, and — given human reproductive patterns — likely not that many generations in the past — you’re likely to find a male who had male siblings. Stop there and go over to the siblings — every one of the males you can find. And then come back down their family trees looking for that one living son of a son of a son who’s willing to take a DNA test for you.

So in this illustration, you — as the female with no brothers, no living father, no uncles, no male cousins — you’d go up your line past your lonely-only grandfather and past your lonely-only great grandfather back to your second great grandfather… who had a brother.

Go over to that man, who’d share that YDNA you’re looking for: both he and your second great grandfather would have inherited their YDNA from your common ancestor, your third great grandfather.

Then come down his line to every living male among his descendants. Those folks in the last generation are fourth cousins — and have the same YDNA your father had.

The same thing works for mtDNA except that you’d be looking for the female-line descendants of daughters of a common female ancestor, rather than the male-line descendants of a common male ancestor.

The beauty of both YDNA and mtDNA is that they tend to be so stable — changing so little from generation to generation — that we can keep going up the generations as far as we can trace the records to find that one male or one female who had descendants that will produce the test candidate we need. If we can find that test candidate we can be matched with him or her even if many generations stand between us and our most recent common ancestor.

That’s much less likely to be true with the more common autosomal DNA tests, where our chances of matching drop off quickly: even at the third cousin level, one out of every 10 pairs of third cousins won’t have enough DNA in common to match; at the fourth cousin level, about half won’t have enough in common to match; and at the fifth cousin level, nine out of 10 may not have enough in common to match.5

But for both YDNA and that direct paternal line and mtDNA and that direct maternal line, the odds are that you’ll run out of records to find the test candidate long before you run out of DNA to match.

So don’t give up too fast on the idea of getting an answer to a research question with YDNA or mtDNA.

And don’t ever give up until you look up, over, and down.

SOURCES

- ISOGG Wiki (http://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Y chromosome DNA tests,” rev. 4 Dec 2016. ↩

- Ibid., “Mitochondrial DNA tests,” rev. 1 Aug 2017. ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Niall of the Nine Hostages,” rev. 26 Dec 2017. ↩

- See “What does the Niall of the Nine Hostages badge on my personal page mean?,” The Family Tree DNA Learning Center (https://www.familytreedna.com/learn/ : accessed 6 Jan 2018). ↩

- Ibid., “See What is the probability that my relative and I share enough DNA for Family Finder to detect?.” ↩

Sometimes you are not the correct person in your family to test to reach your desired target ancestor. I have gone to a female first cousin to get my paternal grandmother’s haplogroup. I have gone to a

male 3rd cousin — once removed to get a surrogate who could reveal the male haplogroup of my 2nd great-grandfather and verify a long paper trail back to 1600. BUT examine potential surrogates with an atDNA test. We spent several hundred dollars on yDNA tests using a surrogate who was alleged to be my wife’s 1st cousin — once removed. In recent years after atDNA testing became available. This alleged surrogate turned out not to be closely related to other members of my wife’s family.

The possibility of a misattributed parentage situation always exists, of course, which is why we should also test everyone that we can, with every test we can afford!

I have that situation but am fortunate that I have a brother and he’s been tested. He is the only son of an only son of an only son etc. Sadly, though even 10 years out from testing his YDNA and doing autosomal testing, uploading to Gedmatch and MyHeritage etc., still not a single match with the same surname. And, only 10 matches total on YDNA that are too far removed to do anything with. Carol Rolnick says my case is unique and difficult. Boy, is she right. But, I’ll keep looking.

Your recommendation is excellent and should work for most people.

Thanks Judy.

If it was easy, it wouldn’t be so much fun, now, would it… 🙂 The only matches my brothers have on YDNA are to each other…

Oddly enough, my husband and I were just discussing this last night and what I would have to do to find someone to test for yDNA. We came up with exactly what you propose. My father’s only brother had only daughters. His father had one brother who never married. His father, my ggrandfather had three brothers. One died at 16 at Antietam, and one disappears after being called to a church in SC, but the younger brother did have two sons and I am in touch with at least one of those son’s female descendant, whom I hope can lead me to a son or grandson that I can persuade to take the test with me paying for it. If no candidate there, I will investigate the progeny of the second son, and if no luck, go back yet anther generation to the gggrandfather, who had at least 2 brothers. How I wish I had been aware of yDNA testing prior to 1993 when my Dad died. Thanks for the great blog posting. I have printed it out with the picture so I can remember how to do it. You have articulated much more clearly something I was stumbling around to find.

Good for you for sticking with this! Keep at it! That YDNA candidate is out there somewhere…

In your note 4, you refer to the Niall badge. however this is not a useful reference as the badge may indicate being M222 but it certainly does not indicate being a descendant of Niall of the Nine Hostages. FTDNA should have removed this badge years ago as the research which resulted in its creation, is out of date and superceded with SNP evidence.

I certainly agree that being M222 doesn’t mean being a descendant of Niall… but if the possibility of getting that badge is enough to help me convince a cousin to test. I’ll go for it…

Hi Judy

You are spot on as usual.

One question …. how do you go about persuading folks who you might have targeted, to actually do a DNA test — especially a Y-DNA Test.

I’m happy to sponsor (or part-sponsor) several blokes who I have identified as potentially distant cousins (same surname and similar places of origin).

I guess with my kinsmen we’re all Scotch-Irish (Gaelic-descended) men of one line or another, but being men …..!

May be I should set up a “family group” with some pre-purchased kits, and then offer selected fellows an opportunity to test at a “give-away price” or as a group freebie!

Any suggestions and tips would be most appreciated!

Warm regards

Dave

This worked for me and my male cousin, both of us descendants of sisters and of our ancestor’s first wife. Not finding any male descendants of the first wife, we switched to the seconf wife and located a descendant willing to test (at our exoense, of course!). Through the years he has gotten 6 good matches, 2 of them 67-marker matches with a Genetic Distance of 1, one of them just this week! This is bringing us closer to our goal of narrowing down who our ancesto’s father might have been, but, just as encouraging, we are sure that we are researching his correct line.

Excellent! Good luck to you!