Those wonderful California records

It was the eighth of August 1889, and Alice Wright, wife of Silas Wright, a resident of the County of Orange, State of California, came into the office of the County Recorder at three minutes past 11 a.m.

There and then, to the Deputy Recorder J.H. Adams, she listed her property: ten cows; 12 heifers; 11 steers; and two horses.1

On the 29th of August, Fannie Wells, wife of Oscar Wells, of the town of San Juan Capistrano in Orange County State of California, listed hers: a two-horse spring wagon; one bay horse named Barney; an organ; a set of carpenter tools; a set od double harness and a sulkey plow; and one Stowe sewing machine.2

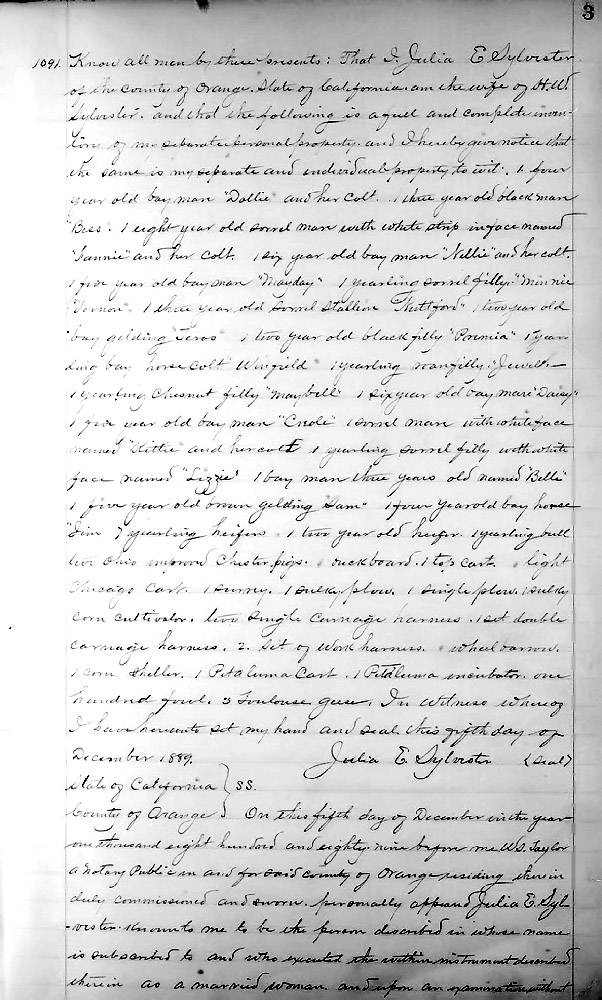

On the fifth of December, it was Julia E. Sylvester’s turn. She was the wife of H.W. Sylvester of the County of Orange, State of California, and she claimed as her property 23 horses; seven heifers; one bull; two pigs; 100 fowl; three geese; and a variety of carts, harness and similar items.3

On the fifth of December, it was Julia E. Sylvester’s turn. She was the wife of H.W. Sylvester of the County of Orange, State of California, and she claimed as her property 23 horses; seven heifers; one bull; two pigs; 100 fowl; three geese; and a variety of carts, harness and similar items.3

On the 11th of December, Miriam M. Fosdick joined the crowd, claiming land, a house, a baking oven and all the personal property in those improvements on a tract in Orange County. Her husband, Clarence W. Fosdick, signed off on that one.4

Now an awful lot of this doesn’t look much like the typical property you’d expect a married woman to own in 1889. So… what in the world was going on in those months in 1889 in Orange County, California?

Yes, The Legal Genealogist is poking around in the records and laws again, preparing for this Saturday’s Genealogy Bash of the Orange County California Genealogical Society at the Huntington Beach Central Library. (And yes, online registration is still open. Come on down!)

And these records of married women are truly gems.

The records exist because of California law and, in fact, because of its entire legal history. I’ve written about this before,5 but it’s worth taking a quick look again.

And that legal history begins with Spain and then Mexico and their control over California, since Spanish law recognized separate property of husband and wife individually and community property owned by the two jointly. That’s a whole lot different from the English common law, which pretty much gave all ownership and control over property to the husband.

When Mexico gave up its claims to California in the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, to end the Mexican War, it extracted a promise that the United States would guarantee the property rights of former Mexican citizens.6

When California put together its first State Constitution in 1849, it wrote those protections in:

All property, both real and personal, of the wife, owned or claimed by marriage, and that acquired afterwards by gift, devise, or descent, shall be her separate property; and laws shall be passed more clearly defining the rights of the wife, in relation as well to her separate property as to that held in common with her husband. Laws shall also be passed providing for the registration of the wife’s separate property.7

And it followed up by statute on 17 April 1850, also protecting the right of separate property, and — as long as the wife filed a full and complete inventory of (her) separate property — “all property belonging to her, included in the inventory, shall be exempt from seizure or execution for the debts of her husband.”8

That’s a pretty powerful incentive to go in and register your property: to keep the men’s debts from impacting the women’s property.

So now we know why the women were going in to record their property.

But 1889 is a looooooong time after that law was enacted in 1850. So… why then?

It’s because, in 1889, something happened that changed things. It’s what my friend, colleague and mentor Thomas W. Jones, Ph.D., calls a triggering event: it triggers the need for action.

And what particularly triggered these records?

It was the creation of a new county.

On the fourth day of June 1889, a referendum was held for or against the creation of a new county from Los Angeles County. The act to authorize the vote had passed 11 March 1889; the vote in favor was 2,509 to 500. And, with that vote, Orange County was born.9

So the reason why the women of Orange County were recording their property in 1889 was that Orange County didn’t exist before 1889.

Just another example of how knowing the law helps us understand the records.

SOURCES

- Orange County, California, Married Women’s Separate Property Book 1: 1-2 (1889); Orange County Clerk-Recorder’s Office, Santa Ana; digital images, “Married women separate property, 1889-1925,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 25 Feb 2018). ↩

- Ibid., Married Women’s Separate Property Book 1: 2. ↩

- Ibid., Married Women’s Separate Property Book 1: 3-4. ↩

- Ibid., Married Women’s Separate Property Book 1: 4-6. ↩

- See e.g. Judy G. Russell, “Revisiting the women and early California law,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 20 Sep 2017 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 25 Feb 2018). ↩

- Article VIII, “Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo; February 2, 1848;” html version, Yale Law School, Avalon Project (http://avalon.law.yale.edu : accessed 25 Feb 2018). ↩

- Constitution of California, 1849, Article XI, § 14, in Constitution of the State of California (Sacramento: State Printing Office, 1915), 234; digital images, Internet Archive (http://www.archive.org : accessed 25 Feb 2018). ↩

- “An Act defining the rights of husband and wife,” 17 April 1850, especially §§ 3-5, in Theodore H. Hittell, The General Laws of the State of California: from 1850 to 1864, Inclusive (San Francisco : Bancroft & Co., 1872), I: 516; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 25 Feb 2018). ↩

- See Phil Brigandi, “The Birth of Orange County,” Orange County Historical Society (http://www.orangecountyhistory.org/ : accessed 25 Feb 2018). See also “California: Individual County Chronologies–Orange,” Atlas of Historical County Boundaries, The Newberry Library (http://publications.newberry.org/ahcbp/index.html : accessed 25 Feb 2018). ↩

I’m so bummed I didn’t realize you were going to be speaking in HB this weekend! If I had, we definitely would _not_ have planned to be in the mountains this weekend. 🙂

You could always change your plans… 🙂

Believe me, I’m tempted to! But I’ve got to spend a weekend with living family from time to time. 😀

At the demise of a husband in 1916 and the property was then the separate property of the wife, were there any legal records required to register the property with the county? Was probate required if there was no will?