….let me go

Reader Barbara Schenck is working on a Missouri estate file and came across a couple of documents that have her perplexed.

The case began early in 1843 in Polk County, Missouri, when one James K. Mallicoat died without leaving a will. His widow Nancy applied to be the administrator of the estate. In the May term of court, her bond as administrator was approved.1

Within a year, her sureties — the securities on her bond as administrator — were bailing out on her, asking the court to be released from their liability on her bond. In November of 1843, Henry King was relieved,2 and in May 1844 John Hunt and Jonathan Rice were excused.3

So, Barbara asks, “what’s going on? Why are all these guys bailing out?” And of course “Is there a record I’m not finding so far that explains what’s going on?”

The first thing to understand in trying to parse through a case like this is exactly what the sureties or securities were all about.

Anybody who was allowed by the court in a probate case to handle the money or assets of another person — and that included the estate administrator in cases without a will, or the executor in cases with a will, or the guardian of a minor — had to promise to do the job right and for the benefit of the persons who ultimately were going to receive the money or assets.

So this person is generally regarded in the language of the law as a fiduciary: “The term is derived from the Roman law, and means (as a noun) a person holding the character of a trustee, or a character analogous to that of a trustee, in respect to the trust and confidence involved in it and the scrupulous good faith and candor which it requires. Thus, a person is a fiduciary who is invested with rights and powers to be exercised for the benefit of another person.”4

But the court wasn’t about to simply take the person’s word for it that the job would be done right and the assets managed for the benefit of those who were ultimately going to receive the money or assets. That promise to do things right was ordinarily bound up with a penalty if the job wasn’t done right: an amount of money or property that the court could take to try to make things right.

That’s what the bond is all about: it’s the written promise to do the job right and putting up security or surety for the financial penalty if it wasn’t done right. Posting the bond didn’t mean actually handing over money or assets; it just meant showing that the person had enough money or assets to cover the amount of the bond if it ever became necessary for the court to go after it.

And, in most cases, the person appointed or named didn’t have enough assets personally to cover the amount of the bond by himself or herself. That’s where the other people involved in the transaction come into play.

Known as sureties or securities, you can think of these folks as co-signers: they’re on the hook every bit as much as the person who’s serving as administrator or executor or guardian if that person doesn’t do the job right. The term surety in the law means “one who at the request of another, … becomes responsible for the performance by the latter of some act in favor of a third person.”5 The suretyship itself is the agreement “whereby one person engages to be answerable for the debt, default, or miscarriage of another.”6 And they’re sometimes called securities since that’s the “name … sometimes given to one who becomes surety or guarantor for another.” 7

In other words, if Nancy didn’t do a good job, if the court ever had to go after her because she wasted the assets of the estate, the folks who signed onto the bond with her would be as responsible as she was.

In this particular case, Nancy was on the hook for a very large amount of money: in June, 1843, the court found her to be indebted to the estate to the tune of more than $2,300 in notes, accounts and a bill of sale — a small fortune in 1843.8 That’s about twice the amount of any other estate record in the same volume.

Now it’s not at all clear just how well Nancy was doing handling that much of an estate. The court record is, as Barbara notes, chock full of cases where creditors of the estate had to go to court to collect, and each of these cases carried court costs being assessed against the estate as well as the amount of the debt recovered.

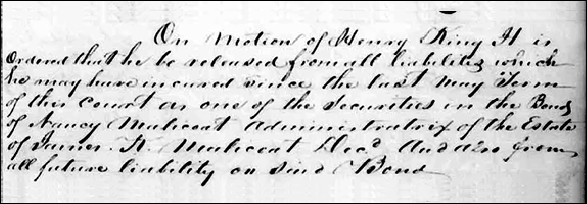

There are, for example, two of those cases recorded in November 1843 — not huge sums, but mounting up: $10 plus damages plus costs; $12.75 plus damages plus costs.9 And you have to think that it’s not simply a coincidence that it’s right after those two cases that the first application to be relieved as Nancy’s surety is recorded: “On motion of Henry King, It is Ordered that he be released from all liabilities which he may have incurred Since the last May Term of this Court as one of the Securities in the Bond of Nancy Malicoat Administratrix of the Estate of James K. Malicoat Decd And also from all future liability on said Bond”.10

The same was true in 1844: another raft of these small unpaid claims with costs and damages being assessed.11 And it was right after those claims that the second two securities were released, and that Nancy was ordered to find others to co-sign her bond.12

In other words, Nancy may not have been doing the best job handling the money for this estate.

And if she didn’t, and was found liable to the estate, guess who was also on the hook?

Her sureties, the securities, those co-signers who had promised that she would do a good job.

So it’s not at all uncommon for securities or sureties who aren’t entirely sure that the principal is doing the job right to ask to be relieved, to get off the hook, to protect their own assets from claims.

That’s not a sure thing of course: the court didn’t try to take Nancy out of running the estate, and it may simply have been that the claims that went to court were ones she legitimately felt were questionable and she wasn’t going to pay them without the court saying so.

And there is of course another possible explanation for why the sureties may have wanted to be relieved: the men who’d originally put up their assets to stand surety may have needed to free up those assets for other reasons. They couldn’t use them again, as security for other debts, and may not even have been able to sell their own property as long as they were obligated on the bond.

So there’s no one-stop-shopping for records to explain this case — to get a full picture of what was happening, a researcher will have to read through the court minutes right to the end of the probate case to see what happened with this estate and in the regular court minutes to see if there was a reason why these particular men might have wanted to free up their assets for other things.

But at least understanding what the bond was, what the securities were all about, the relative value of this estate, and the apparent issues Nancy was having running it, will give a researcher a starting place.

Hey… nobody ever promised this stuff would be easy…

SOURCES

- Polk County, Missouri, Probate Record Book A: 175, 4 May 1843; digital images, “Probate records, 1835-1906,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 10 June 2018), imaged at Missouri State Archives, Jefferson City. ↩

- Ibid., A: 196, 6 November 1843. ↩

- Ibid., Probate Record Book A: 238, 7 May 1844. ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 490, “fiduciary.” ↩

- Ibid., 1142, “surety.” ↩

- Ibid., “suretyship.” ↩

- Ibid., 1073, “security.” ↩

- Polk County, Missouri, Probate Record Book A: 178, 20 June 1843. ↩

- Ibid., Probate Record Book A: 193, 6 Nov 1843. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., Probate Record Book A: 231, $22; Probate Record Book A: 237, $43. ↩

- Ibid., Probate Record Book A: 238, 7 May 1844. ↩

Thank you, Judy, for the providing further understanding of surety and securities for me in the Mallicoat case. Don’t worry, I’ll be reading the pages!

One of those other reasons might have been that they wanted to move out of the area. This reminds me of something I read this morning in some NC Probate files. In the will of Jonathan King of Buncombe Co NC originally written in 1853, he had appointed sons Noah & Caleb as executors of his will. He adds a codicil in 1859 with a few changes…one of which is removing Noah as executor as he has moved out of the state. This makes me wish Noah was my ancestor but my Kings are in TN at this point and have been for at least 2 or 3 generations.

Right, and needing to free the property to sell it to move would be the issue.