To the families of the victims…

The Legal Genealogist‘s first cousin once removed just couldn’t understand the whole notion of genealogy when it came up in a conversation years ago.

He could not for the life of him wrap his head around the idea of wanting to get to know distant family members … or what he thought of as ancient family history.

I remember trying to explain to this man who had walked my mother — his first cousin — down the aisle at her wedding to my father. “Some people collect coins,” I remember telling him. “Others collect stamps. Me? I collect relatives.”

Everyone laughed.

Then his face grew very serious. “What do you do,” he asked, “when you find one that … well … you’d rather not have?”

“Throw him back,” I said. And I remember smiling — not really believing I would ever find such a one.

Until I did.

A fifth cousin. One I never met. One I never wanted to meet. A fifth cousin whose acts were so abhorrent and so incomprehensible to me that — as hard as I have tried — I simply can’t come to terms with having him anywhere in my family tree, even at the far distant remove of fifth cousin.

Fifth cousins means we share a pair of fourth great grandparents. William Killen and his wife — name unknown — were both alive in 1830;1 neither can be found in 1840. The different children of theirs that we descend from were born in the 1790s.2

That’s a long time ago. And there’s been a lot of water under the bridge separating my branch of the family from my fifth cousin’s branch of the family. Until I really got into genealogy, I’d never even heard the name.

But the evidence still says that Edgar Ray Killen of Philadelphia, Neshoba County, Mississippi, was my fifth cousin.

Now… I don’t need to “throw him back.”

Life took care of that for me, a year ago yesterday, when he died in Parchman, Mississippi.3

Parchman.

Where the Mississippi State Penitentiary is located.

And where Edgar Ray Killen died, at the age of 92, after having spent only the last 12-plus years of his life in prison for a crime that is just unthinkable.

Edgar Ray Killen, you see, was a Baptist preacher — and a founding member of the Ku Klux Klan in the Philadelphia area. He was the Klan’s chief recruiter in that area. And one night in June of 1964, he sent a bunch of Klansmen out with a Neshoba County deputy sheriff to waylay three young civil rights workers who had come to Mississippi during the Freedom Summer drive to register Southern black voters.4

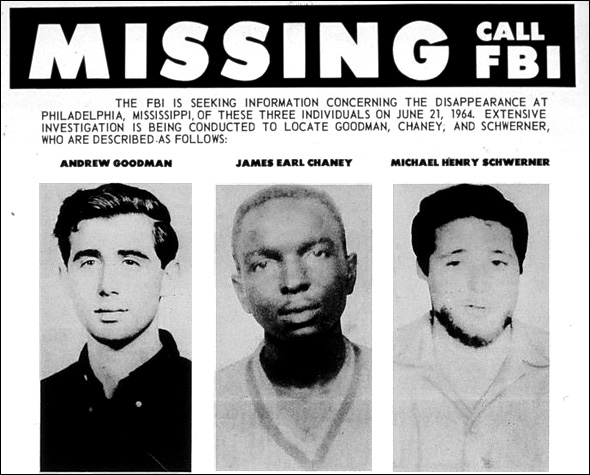

Those three young men disappeared that June night. Their bodies were found weeks later buried under an earthen dam. Their names were Andrew Goodman, James Earl Chaney, and Michael Henry Schwerner. Goodman was just 20 years old when he died; Chaney was 21; Schwerner was 24. Their deaths were investigated by the FBI under the case name MIBURN — Mississippi Burning,5 a name that inspired the 1988 movie “Mississippi Burning” — and pushed forward the cause of civil rights in the United States.

Killen wasn’t with the Klansmen when the young men died. Other Klansmen said he’d arranged to go to a local funeral home to attend a wake in order to set up an alibi. When he originally stood trial in federal court in 1967, one member of the jury held out and caused a mistrial — she said later she could never vote to convict a preacher. He wasn’t brought to justice until 2005, when the State of Mississippi finally indicted him for murder.6

Because Killen hadn’t been at the scene, the jury returned a verdict of manslaughter rather than murder. But the trial judge sentenced him to the maximum 20 years in prison for each of the three deaths with the sentences to run consecutively — a total of 60 years in prison for a man then 80 years old.7 It was clear he would die in prison, and die in prison he did, one year ago yesterday.

So… what do you do when genealogy leads you to a relative like this one? When you find one that … well … you’d rather not have?

When you know that this fifth cousin died miserable and alone in prison, rather than spending his twilight years at home, but you also know that that doesn’t begin to make up for the fact that his actions directly contributed to the deaths of three young men who were doing no more than exercising their rights as Americans — and encouraging others to do the same? When you know that nothing can make up for the fact that those young men died a horrific death — while he lived, free and clear and an outspoken unrepentant racist, for 41 years to the day after the crime before the law finally caught up to him?8

I don’t know how others will choose to deal with it. I only know how I will choose to deal with it, here on this day after the first anniversary of the death of Edgar Ray Killen.

I can’t make it right. I can’t make it up to the families of those young men. But there is one thing I can do that, I can hope, may prove to be some small comfort to the members of those families.

I can let them hear something from a member of Edgar Ray Killen’s family. Something, I suspect, they’ve not heard once in the going-on-45 years since the Freedom Summer of 1964. Something that, perhaps, they particularly need to hear now in this troubled time in which we live.

To the families of the victims, Andrew Goodman, James Earl Chaney, and Michael Henry Schwerner, from this member of the family of this perpetrator, Edgar Ray Killen:

I am so very sorry for what my family did to yours.

May you know that their lives were not in vain.

May their good deeds be remembered.

May their memories be a blessing.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “A long overdue apology,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 12 Jan 2019 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed (date)).

SOURCES

- 1830 U.S. census, Rankin County, Mississippi, p. 167 (stamped), William Killen household; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 11 Jan 2019); citing National Archive microfilm publication M19, roll 71. ↩

- I descend from daughter Wilmoth (Killen) Gentry, born about 1794. See e.g. 1850 U.S. census, Neshoba County, Mississippi, population schedule, p. 119(A) (stamped), dwelling 74, family 79, Wilmoth Gentry; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 11 Jan 2019); citing National Archive microfilm publication M432, roll 378. This cousin descends from son Henry, born around 1792. See e.g. ibid., p. 149(B) (stamped), dwelling 477, family 499, Henry Killen. ↩

- See Richard Goldstein, “Edgar Ray Killen, Convicted in ’64 Killings of Rights Workers, Dies at 92,” New York Times, online edition, posted 12 Jan 2018 (https://www.nytimes.com/ : accessed 11 Jan 2019). ↩

- See Brett Barrouquere, “The last days of a Klansman: Edgar Ray Killen remained a defiant racist in prison until the end,” Hatewatch, posted 21 Mar 2018, SPLC.org (https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/ : accessed 11 Jan 2019). ↩

- See “Mississippi Burning”, History: Famous Cases & Criminals, FBI.gov (https://www.fbi.gov/ : accessed 11 Jan 2019). ↩

- Jerry Mitchell, “Klansman who orchestrated Mississippi Burning killings dies in prison,” Jackson (MS) Clarion-Ledger, online edition, posted 12 Jan 2018 (https://www.clarionledger.com/ : accessed 11 Jan 2019). ↩

- Jerry Mitchell, “No mercy for Killen: Ex-Klansman gets maximum prison term of 60 years,” Jackson (MS) Clarion-Ledger, 25 June 2005, p.1, cols. 1-8; digital images, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com/ : accessed 11 Jan 2019). ↩

- See Marwa Eltagouri and Manuel Roig-Franzia, “Here’s what happened the day a former KKK leader was finally convicted of killing 3 civil rights workers,” Washington Post, online edition, posted 12 Jan 2018 (https://www.washingtonpost.com/ : accessed 11 Jan 2019). ↩

Thank you for sharing this story, Judy — as painful as it must be to all parties! It is only when we who are living today face squarely the injustices that have been inflicted by our ancestors and kin, can we hope to ever heal our nation.

Would that we could all step up to the plate, accept our common responsibility, and acknowledge that what was done was wrong — even evil. Then as you say perhaps we can begin to heal.

This is a beautifully written post, Judy. I hope it brought you some peace as you wrestled with the knowledge of your family member’s actions. Even more, I hope the family members of the victims will find it and feel some peace of their own.

I truly hope it will bring some small measure of comfort to the Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner families, and not simply tear open the wounds. I can’t begin to imagine how painful their losses were… and are.

Judy, I think often of how civic heroes, such as these three courageous young adults, faced violence to do what is morally and ethically required of all people of good conscience. I hope that their sacrifice will not ever be considered as just another dry historical account of history. “Freedom is a constant struggle.” I know we believe it and live it every day.

What’s frightening is realizing how many don’t believe freedom needs to be protected all the time… or are willing to “overlook” it if it’s inconvenient to them at this moment. 🙁

As a person of color…multi-ethnic. This make me sick to my stomach.

Edgar Ray Killen is my 16th cousin once removed.

It’s surely harder for you. But perhaps a little better knowing that not all your Killen cousins, if that’s the line, feel as he did.

I have the victim of a gruesome unsolved murder in my family. I considered using clues from the extensive newspaper coverage to try to find who did it, but ultimately decided not to do so: satisfying my curiosity wouldn’t justify inevitability burdening his descendants with the knowledge that they have a murderer in their family. My gggma had to accept not knowing, and I choose to.

That’s surely one appropriate choice, given the time frame.

I’m sure it took alot to post this, Judy. I have found a not-too-distant relative with a questionable background and it was tough placing him in my tree; I made sure I attached a message in the Notes section. Thanks for posting!

I think in reality it was more painful being silent than speaking out. I wish more families would acknowledge their roles in this sort of thing in the past and offer apologies. Maybe we could then begin to heal.

Judy, what a dreadfully hard, horrific and yet beautiful post & tribute to those three young me.

We cannot be held responsible for the actions of others, we shouldn’t bury our heads in the sand that things have happened. You have not. You have shared your inner values & recognition for those events.

It’s when the wounds are lanced and open to light and sunshine that we can all begin to heal.

Thank you. Just thank you.

They cannot be brought back. But their good works and intentions can inspire us still. Thank you for the post.

I remember that murder as well as the very active, very needed civil rights movement that resulted in deaths such as these. I think your acknowledgment and apology are very important. Thank you.

I applaud your humility. It’s hubris to think that ANY family doesn’t have its fair share of evil.

You get what it means to be human. The responsibilities as well as the privileges. Thank you for reminding the rest of us.

Congratulations, I have included your blog in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

https://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2019/01/friday-fossicking-18th-jan-2019.html

Thank you, Chris

I can see that this has taken quite a lot of thought before writing…you have given us all a valuable lesson. Thank you.

Judy,

Thank you for your apology to the families of the victims, Andrew Goodman, James Earl Chaney, and Michael Henry Schwerner. You have set a good example for us. It takes a lot to be humble in a situation such as this.

Martin Luther King Jr. Day (today); an extra meaningful experience to read this thoughtful piece today.