Those marriage bond issues again

It’s not an easy thing to wrap our heads around.

For those of us living in the 21st century, understanding what a marriage bond was, how it worked, and what it was used for just isn’t the easiest thing to manage.

We all — The Legal Genealogist included — grew up in the era of marriage licenses. We understood the rules: you trot down to the local clerk’s office, fill out a form, meet other prerequisites, and pay a fee. You walk out of the office, license in hand, and head off to get married.

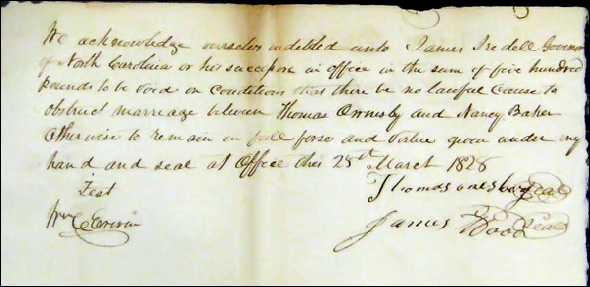

So coming across a document like this one, executed in 1828 in Burke County North Carolina, with respect to the marriage of Nancy Baker and Thomas Owensby, can make a genealogist’s head spin.

Reader Beverly Duncan put together her list of questions about marriage bonds — some of which have been written about here before1 — and it’s a good list for those who encounter these documents. Here’s what she wanted to know:

• When a man puts up a marriage bond and decides not to marry how much of his money does he forfeit?

• Are there two parts to the bond (as in modern day) — did they only have to put up 10% of the bond amount? Would they have to pay the full amount of the bond?

• If they do marry, do they get the original amount paid (deposit or in-full) returned to them?

• In other words, how much did they have to pay if they did not marry? if they did marry?

• Were there other rules about the bond that we don’t usually research?

So let’s take another look at this peculiar-to-us kind of marriage records.

Remember that, for the longest time, the way folks got married was that marriage banns2 were read from the pulpit or posted at the door of the local church (and/or the courthouse and/or the tavern…). Usually, banns were read on three consecutive Sundays or posted for three weeks.

For example, in Virginia, a 1705 statute required “thrice publication of the banns according as the rubric in the common prayer book prescribes.”3 In North Carolina, as of 1715, couples had to have “the Banns of Matrimony published Three times by the Clerks at the usual place of celebrating Divine Service.”4

That notice that two people were going to marry had one purpose and one purpose only: to make sure folks knew there was a wedding in the offing so that they had a chance to come forward and object if there was some legal reason why the marriage couldn’t take place.5 In general, that meant one of the parties was (or both were) too young, one of them was (or both were) already married, or the law prohibited the marriage because they were too closely related.6

When folks married without banns, however, particularly when they married some distance away from where they were known, there wasn’t the same opportunity in advance to have folks “speak up or forever hold their peace.” The bond then stepped into the breach.

What that bond actually was, then, was a form of guarantee that there wasn’t any legal bar to the marriage. Enforcing the guarantee was a pledge by the groom and a bondsman — usually a relative — to pay a sum of money, usually to the Governor of the State (or colony if earlier, or to the Crown if in Canada7), if and only if it actually turned out that there was some reason the marriage wasn’t legal. The bond shown here, for example, for that 1828 marriage was a promise by the groom Thomas Owensby and his bondsman, James Wood, to pay the Governor of North Carolina five hundred pounds, but it provided that it was “void on condition that there be no lawful cause to obstruct marriage between Thomas Ownesby and Nancy Baker.”8

Now… for Beverly’s questions.

In general, except for a filing fee, no money actually changed hands when the bond was executed. Unlike modern bonds, where an actual amount of money has to be posted or some percentage as insurance that there actually are assets to cover the bond amount, early bonds including marriage bonds were simply a written promise. The idea was that, between the groom and his bondsman (or bondsmen in an appropriate case), they would have enough assets to cover the amount if it ever became necessary to forfeit the bond.

So because no money changed hands up front, no money was ever refunded to a groom or a bondsman.

And no money ever had to be paid under any circumstances if there never was a marriage. The bond wasn’t any kind of a promise from the groom to the bride that he was going to marry her. Just as people today can get a marriage license, and then get cold feet, never going through with the marriage itself, people could execute a marriage bond and then, for whatever reason, not go through with the marriage. At some point, those who signed the bond might want or need to have it canceled to free up their assets for another or different kind of bond. But not getting married didn’t cause the bond itself to be forfeited.

The only thing that would cause the government authority to forfeit the bond — in other words, go to court to have the money actually paid over9 — would be if the condition set in the bond ever came to pass: if it ever appeared that there actually was “lawful cause to obstruct marriage between Thomas Ownesby and Nancy Baker.”10

Now… don’t go looking for a whole bunch of legal cases against grooms and their bondsmen trying to forfeit marriage bonds. In general, the bond did exactly what it was supposed to do: ensure that those who married were legally able to marry. Those who were willing to execute a bond when they actually weren’t legally free to marry generally did it at times and in places where the chances were pretty good they wouldn’t get caught.

But Beverly’s last question may be the best of all — what other rules about bonds we should look at in our research. First and foremost, remember that bonds were usually required by law. So we need in every case to look at the law of the time and the place. It’s The Legal Genealogist‘s mantra: to understand the records, we have to understand the law.

The other thing we need to remember is that the amount of money that might be forfeited was fairly substantial. Losing the amount set in Thomas Owensby’s bond — 500 pounds in 1828 North Carolina — was a pretty big financial hit. When the laws changed to use dollar amounts in 1837 North Carolina, the bond amount was set at $1,00011 — a truly significant sum for that time and place.

Think about that: if you’re a bondsman, in effect, you’re being asked to co-sign a promissory note. If it’s ever forfeited, you’re on the hook every bit as much as the groom. Do you co-sign a note for a stranger? For an acquaintance? It’s much more likely, and extremely common, that the bondsman on a marriage bond — or in fact on any kind of bond — is family. At a minimum, that bondsman is friend, associate or neighbor — in other words, a member of the groom’s FAN club12

And that is always, always, always a fact we want to record, and then go on to investigate all the records of that association.

So as genealogists we should always chase that marriage bond — and, in fact, all bonds — as part of our reasonably exhaustive research. And when we do so, we need to remember what it is… and what it isn’t.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “Revisiting the bond,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 8 Apr 2019).

SOURCES

- See Judy G. Russell, “The ties that bond,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 25 Jan 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 8 Apr 2019). Also ibid., “Bonding the bride and groom,” posted 17 Nov 2014. ↩

- “Public announcement especially in church of a proposed marriage…” Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (http://www.merriam-webster.com : accessed 8 Apr 2019). ↩

- Virginia Laws of 1705, chapter XLVIII, in William Waller Hening, compiler, Hening’s Statutes at Law, Being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia from the first session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619, vol. 3 (Philadelphia: Thomas DeSilver, printer, 1823), 441; digital images, HathiTrust Digital Library (https://www.hathitrust.org/ : accessed 8 Apr 2019). ↩

- North Carolina Laws of 1715, chapter 8, in William Saunders, compiler, Colonial Records of North Carolina, Vol. 2 (Raleigh, N.C. : P.M. Hale, State Printer, 1886), 212-213; online version, “Colonial and State Records of North Carolina,” Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/ : accessed 8 Apr 2019). ↩

- See generally Susan Scouras, “Early Marriage Laws in Virginia/West Virginia,” West Virginia Archives & History News, vol. 5, no. 4 (June 2004), 1-3. ↩

- Maryland by statute required marriages to follow the Church of England Table of Marriages, drawn up in 1560, that said when relatives were too closely related. See Chapter 12, Laws of 1694, referenced in Acts of the General Assembly Hitherto Unprinted 1694-1729 (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1918), 1; digital images, Archives of Maryland series, vol. 38: 1, Archives of Maryland Online (http://aomol.msa.maryland.gov/ : accessed 8 Apr 2019). For that table, see F. M. Lancaster, “Forbidden Marriage Laws of the United Kingdom,” Genetic and Quantitative Aspects of Genealogy (http://www.genetic-genealogy.co.uk : accessed 8 Apr 2019.) ↩

- See “What is a marriage bond?,” Marriage Bonds, 1779-1858 – Upper & Lower Canada, Library and Archives Canada (http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/ : accessed 8 Apr 2019). ↩

- Burke County, North Carolina, Marriage Bond, 1828, Thomas Owensby to Nancy Baker; North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh. ↩

- See Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 508, “forfeiture of a bond.” ↩

- Burke County, North Carolina, Marriage Bond, 1828, Thomas Owensby to Nancy Baker. ↩

- See §2, Chapter 71, “Marriages” in James Iredell and Thomas Battle, compilers, The Revised Statutes of North Carolina (Raleigh: Turner & Hughes, 1837), 1: 386; digital images, Internet Archive (https://archive.org/ : accessed 8 Apr 2019). ↩

- See Elizabeth Shown Mills, QuickSheet: The Historical Biographer’s Guide to Cluster Research (the FAN Principle) (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2012). ↩

On marriage bonds I’ve seen for family members in early to mid 19th century Kentucky, the groom’s bondsman was often a close relative of the bride, such as her brother or father. So both the families had a financial stake in the marriage being legal.

It’s very common for the bondsman to be from the bride’s family, but it wasn’t required and in my own family I’ve seen bondsmen from both sides — and from outside of either family.

One of my treasures was finding the marriage bond for my 3rd great-grandfather, Calvin Stratton. Dated 10 Dec 1810, the bond was for $1250! It was cosigned by David Snow whose identity I still have not determined, except that he did so as a “resident of Davidson County, Tennessee.” Calvin and his bride, Gabriella Johnston/Johnson, lived in Bedford County, and it was much easier to get to the county seat of Davidson County. Many Bedford County residents did their legal business in Davidson at the time. And quickly: the marriage took place the same day the license was issued, and the same place. It was thrilling to see the actual signature of my ggg-grandfather: it was beautifully formed and suggested an educated man. I was to learn later that Gabriella herself was well-educated. The couple went on to have a large family, so obviously the bond was never an issue! This is however, a good reminder that it is a good idea to explore records in surrounding counties, especially in frontier areas where transportation is challenging (or a county seat not yet functional). Or, as in an earlier case in my family, where a young couple in New England eloped against the wishes of their families!

Absent any other contrary information, is the existence of a marriage bond inferential proof of a marriage? I’m thinking of earlier colonial times when church records, newspaper accounts, family bibles, etc. may not exist.

Good question — answered in the blog!

I see that a marriage bond is simply a promise not a record of a marriage. But what if the couple went on to have offspring and the husband left a will naming the wife mentioned in the bond? Without any other contemporaneous evidence of the marriage – church records, banns, newspaper accounts etc., can the bond be used to infer the date of the marriage?

It gives you one bookend: it’s unlikely (though not impossible) that the marriage would not have taken place before the bond was executed. Adding in the DOB (or year at least) of the first child would help narrow it down.

Is the bondsman related to the groom or the bride? Often I see a bondsman who is a brother or uncle of the bride, but once in a while he seems to be related to the groom. If the purpose of a bond is to secure that both bride and groom are eligible to be married, I had thought the bondsman would be related to the bride. But now, looking at some records, that doesn’t always seem to be the case. Did I get it wrong? Or maybe I’m looking at witnesses and not bondsmen? I often see witnesses signing on the left bottom of the document, and the bondsman signing under the groom. Confused! 🙂

The bondsman can be related to either bride or groom — or neither. There’s no legal requirement on that. (If there was, many orphans could never have gotten married!!) Having everybody from the groom’s side wouldn’t make it invalid — that’s no different from all the many years when the only person who ever filled out or signed the marriage license application was the groom. But it shouldn’t ever surprise us to find a member of the bride’s family standing surety in the marriage bond. Either was perfectly common.