A research plan for Margaret’s mother

Everybody needs a research goal to work towards, and many of us set them in our annual resolutions.

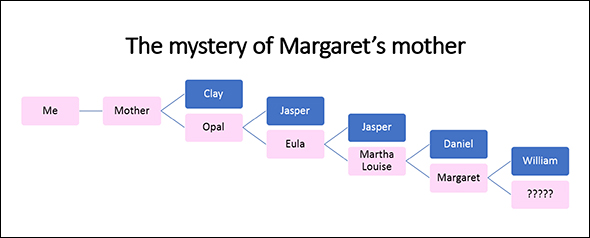

And you may recall that The Legal Genealogist‘s DNA resolution for 2019 was to finally determine — if it’s at all possible — the identity of the mother of Margaret (Battles) Shew.1

Margaret, you may recall, is my third great grandmother. And the problem is that we’re not 100% sure which of her father’s two wives was her mother.

Now you’d think this ought to be really easy. Her father William Battles married Kiziah Wright in Oglethorpe County, Georgia, in 1818.2 And he married Ann Jacobs in St. Clair County, Alabama, in 1829.3 So if Margaret was born during William’s marriage to Kiziah, she’s Kiziah’s child, and if born during his marriage to Ann, she’s Ann’s child, right?

Sigh… not so fast. This isn’t just a first-wife-died-Daddy-remarried case. See, Kiziah sued William for divorce in 1824 alleging that he’d run off with Ann … and they were living in sin. The suit was dismissed for want of prosecution in 1829, apparently when Kiziah died4 clearing the way for him to marry Ann.

Well, that still makes it easy, right? If Margaret was born after William ran off with Ann, then we could still say she was Ann’s child, not Kiziah’s.

Sigh again… Not so fast. Margaret’s birth date — even her birth year — isn’t exactly easy to figure out. The 1850 census shows her as age 23, so born around 1827.5 That’d be well after William allegedly ran off with Ann.

But the 1860 census pegs her age as 38 (birth year around 1822)6 — and that could easily be well before William ran off with Ann.

The other evidence doesn’t really nail this down. The 1870 census has her not aging a single year between 1860 and 1870 — her age is still 38 (birth year around 1832)7 and the 1880 census shows her as 48 (birth year around 1832).8 One other document, a Southern Claims Commission deposition filed by Ann says “Peggy” was 45 in 1874 (birth year around 1829).9

In other words, this when-was-she-born thing means she really could be the child of either Kiziah or Ann, and that’s the question I resolved to answer for once and for all this year.

And here we are, on the DNA Sunday that’s one-third of the way into this year.

So… you may ask… how’s it going?

Um… er…

Does the word “procrastination” mean anything to you?

It sure does to me.

So this post is to force me to get started by enlisting you as my research buddies. Not necessarily ones who’ll help with the research, mind you, though I’ll take all the help I can get. But ones who’ll help keep me going with the research.

After all… I have only eight more months to meet this goal.

So… where does a genealogist start with a question like this one? How about with the new DNA standards just incorporated into Genealogy Standards, published by the Board for Certification of Genealogists?10

And that very first standard requires that we plan DNA tests with an eye towards accomplishing a specific goal, rather than just flinging our DNA out into the wind. It tells us that:

• Our testing plan — if it’s to be effective — has to be “selective and targeted”.11

• We choose what we use in that plan — specific tests, testing companies and tools for analysis — based on their “potential to address” the specific research question we’re trying to answer.12

• And we choose the DNA results from the specific people — whether they’ve already tested or we need to get them to test — when there’s a real potential that their DNA will help answer that specific research question.13

So. Step 1. What test can we use, if any, to help answer this question?

In this particular case, it’s easy to see which type of DNA test we need. It won’t be YDNA — the kind of DNA passed from father to son to son through the generations14 — since Margaret as a female could neither receive nor pass on any YDNA, much less YDNA on her mother’s side.

It won’t be autosomal DNA — the kind of DNA inherited from both parents and used to identify genetic cousins15 — since anybody who descends from either of William’s marriages could match any descendant of Margaret, and there’s no way to know for sure if the match is because of DNA inherited from Margaret’s father, Margaret’s mother or both.

No, if we’re going to answer this question for sure, we need to use mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) — the kind of DNA inherited in a direct matrilineal path16 — to nail down who my mother’s mother’s mother’s mother’s mother’s mother was.

On to Step 2. Who do we need to test?

Clearly, we need to test a direct female line descendant of Margaret, and that’s already been done. Margaret had one daughter, Martha Louise, from whom I descend in a direct female line. Our mtDNA haplogroup is H3g.17

Next, we need to test a direct female line descendant of each of the possible mothers. With Ann, that’s been done as well. A Californian who descends in an unbroken female line from Ann’s daughter Julia — born well after the marriage of William and Ann — also shows an mtDNA haplogroup of H3g and is a perfect match to Margaret’s descendants.18 But it’s not possible to test anyone descended in a direct female line from Kiziah because there’s no evidence that Kiziah left any descendants at all.

So are we done?

No. Because, while the evidence we have is enough to prove Margaret could be Ann’s child, it’s not enough to prove she couldn’t be Kiziah’s child. We also have to eliminate the possibility that Kiziah was also H3g — that she and Ann could have shared a female ancestor further back in time.

And the fact that Kiziah left no known descendants to test doesn’t mean there aren’t any test candidates. Because, of course, Kiziah inherited her mtDNA from her mother — and anyone else who descends from that same woman in a direct female line should have the same mtDNA as Kiziah had.

So… on to Step 3. Identifying other test candidates.

And for that step, we don’t begin with DNA at all. This is plain old-fashioned paper trail genealogy.

Next up: identifying Kiziah’s mother.

Don’t let me get away with not following up on this, okay? Nag me once a month or so if I haven’t posted a follow-up, okay?

I really want to solve this by the end of this year.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “Keeping that DNA resolution,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 28 Apr 2019).

SOURCES

- See Judy G. Russell, “DNA resolutions for 2019,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 30 Dec 2018 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 28 Apr 2019). ↩

- Oglethorpe County, Georgia, Marriage Book 1: 61, Battles-Wright, 12 December 1818; “Marriage Records from Microfilm,” Georgia Archives Virtual Vault (https://vault.georgiaarchives.org/digital/ : accessed 28 Apr 2019). ↩

- St. Clair County, Alabama, Marriage Record 1: 53, Battels-Jacobs, 25 Dec 1829; digital images, “Marriage records (St. Clair County, Alabama), 1819-1939,” FamilySearch.org (https://familysearch.org : accessed 28 Apr 2019). ↩

- Blount County, Alabama, Circuit Court Minutes B: 373-375 (1829); Circuit Court Clerk’s Office, Oneonta, Ala. ↩

- 1850 U.S. census, Cherokee County, Alabama, population schedule, 27th District, p. 136 (back) (stamped), dwelling 1055, family 1055, Danl Shew household; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 28 Apr 2019); citing National Archive microfilm publication M432, roll 3. ↩

- 1860 U.S. census, Cherokee County, Alabama, population schedule, p. 315 (stamped), dwelling 829, family 829, Margaret Shoe household; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 28 Apr 2019); citing National Archive microfilm publication M653, roll 5. ↩

- 1870 U.S. census, Cherokee County, Alabama, Leesburg, population schedule, p. 268(A) (stamped), dwelling/family 15, M. Shew in Baird household; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 28 Apr 2019); citing National Archive microfilm publication M593, roll 7. ↩

- 1880 U.S. census, Cherokee County, Alabama, Township 11, Range 8, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 27, p. 387(A) (stamped), dwelling/family 5, Margaret Shew in A.C. Livingston household; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 28 Apr 2019); citing National Archive microfilm publication T9, roll 6. ↩

- Deposition of Ann Battles, 1 June 1874; William Battles, dec’d, v. United States, Court of Claims, Dec. term 1887–1888, Case No. 967-Congressional; Congressional Jurisdiction Case Records; Records of the United States Court of Claims, Record Group 123; National Archives, Washington, D.C. ↩

- Board for Certification of Genealogists, Genealogy Standards (Nashville, Tenn. : Ancestry. 2019), 29-32, Standards 51-57.) ↩

- Ibid., 29, Standard 51, “Planning DNA tests.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- ISOGG Wiki (https://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Y chromosome DNA tests,” rev. 4 Dec 2016. ↩

- Ibid., “Autosomal DNA ,” rev. 8 Apr 2019. ↩

- “Mitochondrial DNA tests,” rev. 28 Jan 2019. ↩

- For example, my own full sequence mtDNA test results, completed 15 Sep 2010 at Family Tree DNA, show my haplogroup as H3g. ↩

- Full sequence mtDNA test results, M.P., completed 2 Dec 2014, Family Tree DNA. ↩

Once again I had a lengthy reply but since I forgot to check the posting box, it’s all gone. I wish there was a pop up that says CHECK THE BOX to proceed.

Once again, I can only suggest that — as a workaround because this is not something I can control right now — you might consider writing the comment in your favorite text editor and then simply copy-and-paste it into the comment box. That way you’ll never again lose another lengthy reply you graciously spend time writing — and I’ll never again lose the benefit of your thinking.

I’m surprised you seem to put so little weight in the “perfect” full sequence mtDNA match between Ann’s Julia’s descendants and Margaret’s descendants. That seems to get lost in your point that (of course) sharing the same H3g haplogroup isn’t good enough. The hypothesis would be descent from Ann, now you are trying to test that.

Our problem here is that we know Margaret is the daughter of William (we have both DNA and paper-trail evidence of that). But we have essentially NO documentary evidence to distinguish between the two maternal candidates, and we’re dealing with a burned county prior to the requirement of state vital statistics recordation. There are no birth, marriage or death records for Margaret. None of the five children recorded on the 1830 census in the Battles household (who could be children of either Kiziah and born during that marriage, or Ann and born out of wedlock) left records naming their mother. Two died during the Civil War, and the other three before death records were required. The mtDNA evidence may be powerful, but not by itself, since the mtDNA haplogroup H is the most common haplogroup among European women, and there are no good statistics on how frequent the subclade H3g is within the haplogroup. We know it isn’t completely rare, since our baseline tester (no oddball heteroplasmies) has 31 exact mtDNA matches, none of which can be definitively linked to either Ann Jacobs or Kiziah Wright except the one descendant of Ann’s who tested at our request. For that reason, we can’t simply say “well, it’s gotta be Ann” and we don’t have any other good options for testing the hypothesis that it is Ann except to rule out the hypothesis that it could be Kiziah.

Thanks for the clarification on the number of exact matches and their non-relationship among each other. The context is helpful!

As soon as a woman starts aging she lies about her age, at least that’s a common thread in my family tree, why not it’s her prerogative. Take the earliest census as the most accurate. Husbands lie about their age if they are younger than wife, seen it .

I don’t take anything as the most accurate simply because it came first, and especially not a census where we don’t even know who provided the information. We need a LOT more to reach a credible conclusion.

Your post has been most inspiring. We’ve just added the full mtDNA test from Family TreeDNA to my Aunt’s kit. She is 94 years old and we are trying to confirm a 3x great grandmother. I have now set the same goal as you! I look forward to following your post along this research plan. The Mystery Mother. Thank you for the nudge I needed.