The limits on copyright

Reader Dennis Yancey asks a great copyright question.

“If a person transcribes the family record data in a Family Bible,” he asks, “can they claim copyright on this transcription?” And, he continues, “Is the answer to this pretty much the same for any transcription of any document of genealogical value?”

The Legal Genealogist loves questions with easy answers: No and yes, in that order.

Let’s break this down.

Copyright laws around the world are pretty much the same in one critical respect–there’s one fundamental thing that has to be true in order to get a copyright.

The material being copyrighted has to be the original work of the person (or corporate entity that owns the rights to that person’s work) applying for copyright protection.

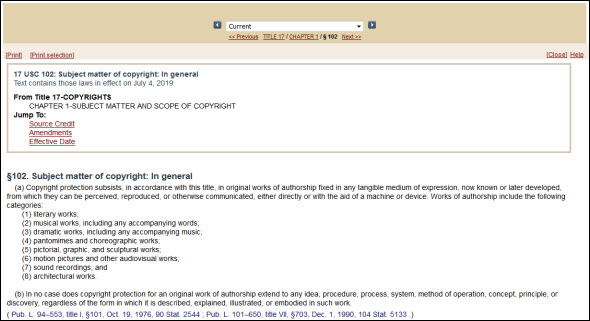

One of the very first sections of the United States law dealing with copyrights puts it this way: “Copyright protection subsists … in original works of authorship …”1

As explained by the U.S. Supreme Court, originality is “the touchstone of copyright protection today… the very ‘premise of copyright law’ (and) ‘constitutionally mandated’” before copyright’s benefits will be extended. It is, the Court said, the “bedrock principle of copyright” that the work “must be original to the author,” that is, “independently created by the author (as opposed to copied from other works)…” In the copyright context, “originality requires independent creation.”2

So the bottom line here is that someone can only get a copyright where “the author created the work without copying from other works.”3

By definition, transcribing that Bible record is copying from other works. No copyright possible there.

So, easy answer: no, the person transcribing that family data from a Bible can’t claim copyright. That person didn’t create the original work. And yes, that’s going to be the answer for any transcription of any document of genealogical value.

Now translations are different. There’s some discretion and judgment involved in translating a work from one language to another, in word choice and interpretation of nuance or colloquial terms. So you can get a copyright on a translation under both international law4 and United States law.5 The new copyright is limited to the new material, and, if the original work is still under copyright, the translation has to authorized by the owner of the original copyright.6

But transcriptions? No. Not original, so no copyright.

Great question, Dennis!

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “Originality counts,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 5 July 2019).

SOURCES

- 17 U.S.C. §102(a), “Subject matter of copyright: In general.” ↩

- Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., Inc., 499 U.S. 340, 345-347 (1991), emphasis added. ↩

- See §§308-309, Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, 3d. ed. (2017), U.S. Copyright Office (https://www.copyright.gov/ : accessed 5 July 2019). ↩

- See ¶ 3, Article 2, Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, WIPO-Administered Treaties, World Intellectual Property Organization (https://www.wipo.int/treaties/ : accessed 5 July 2019). ↩

- See §507.1, “What is a Derivative Work?,” Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices. ↩

- See ibid., §507.2 and §609.1. ↩

Hmm. I get it. I truly do. But that would also seem to mean that if I transcribe an old document (and those who have done so know how much work can go into that sometimes), I not only cannot copyright my transcription, I also cannot request that anyone who downloads it or uses it give me credit for transcribing it, right?

Credit is different. As genealogists, we cite our sources, and anyone using your transcription should cite you as the source of the transcription! This is an ethical constraints, not a legal constraint, but…

Thanks for the clarifications (copyright/credit, ethical/legal). Sometimes I get ahead of myself.

I agree if we’re talking about a single transcription of a single document with no other material. But… And, if one added a suggested citation to the transcription, that would be original, right? And, if one performed extensive image processing to reveal badly faded text and then included the processed image with the transcription, that would be original, right? And, One could copyright a compilation of transcriptions, right? I suggest that the answer is not quite as simple as you presented. In no case, does one get to the original text, but originality can be be imputed to added value and the expression of that added value can be copyrighted.

Under Feist, a compilation could be copyrightable only to the extent that there was some discretion and creativity shown in the selection of materials, and of course to the new materials added. It’s the same thing as reprinting an old book now out of copyright. You can copyright it, but the only thing covered by the copyright is your new introduction and any added text. The original was — and is — not protected.

What about Photos of a Family Bible?

Can the owners of a bible – claim that it was their ancestors who made these bible entries (and thus the original ancestral recorder of the bible had copyright) and as descendants they inherited such copyright?

Nobody can get a copyright on work they didn’t produce AND facts can’t be copyrighted anyway. So this isn’t a copyright issue. BUT the owner of the Bible can set any restrictions he or she wants on access to the Bible and its contents: nobody is under any legal obligation to allow someone else to access an item he or she owns. A museum that owns the only copy of a document can limit who sees it, who can photograph it, who can reproduce it and more. That’s not copyright law, it’s contract law: I as the owner am contracting (agreeing) with you that I will let you see it under these conditions.

What if I want to transcribe a church registry that has been microfilmed and placed on Family Search? Or transcribe a specific county portion of the slave schedule viewed on Ancestry or Family Search? Am I able to transcribe those documents and publish them on my website or in a book without fear of facing violations of copyright law? They are “facts” so I think it would be allowable as long as I don’t copy the actual image. I don’t care about whether or not I can get a copyright.

That won’t be a copyright issue, it’ll be a contract issue. What permissions did FamilySearch have (and thus what permissions can it give you to copy it)?

Thank you. There are no restrictions noted but I’ll look deeper. There is a custodian listed in 1963 but the congregation is no longer active. The records were microfilmed by the NC Dept of Archives and History. Thanks again!

What about an original family bible itself (not copies thereof)

is the writing in the original family bible register – copyrightable?

one could argue it is merely a list of facts and thus can not be copyrighted

does the pre-1923 copyrgight rule apply to items written in a famioly bible pre 1923?

In almost every case, the information written into a family Bible is purely factual: John born on this date. Facts cannot be copyrighted.

I understand the difference between contract law and copyright law

It seems like more and more organizations are loosening their “terms of use” contracts for items that are in the “public domain”.

are there any indications that the courts are not enforcing “terms of use” limitations for items that are clearly in the “public domain” to begin with?

and under what scenarios are “terms of use” not really legally enforceable?

what if the terms of use were never posted on a web site?

what if the person downloading items never read the terms of use?

are there examples you can give of terms of use that are really not legal? or enforeceable?

what if there never were terms of use at the time of download?

Far more than I can deal with in a comment response, and lots out there to read if you want to follow up. Start with https://www.americanbar.org/groups/business_law/safeselling/terms/, https://www.natlawreview.com/article/enforcing-click-through-and-url-terms, https://www.michiganitlaw.com/enforcement-incorporation-online-terms-conditions and keep reading.

It’s my understanding of you compile the transcriptions from numerous Family Bibles into a book.. that book can be copyrighted. The book sands as an original work, regardless of the source materrial.

Yes… and no. You can get what’s called a compilation copyright: it covers your specific selection and arrangement of the transcriptions. But the transcriptions themselves are not original to you and you can’t get a copyright on those. See Circular 14 from the Copyright Office.

What about Photos/scans of a Family Bible? — same rules as a transcript I suppose?

(where there is no original creativigty)

Essentially yes. Plus the information recorded is pure fact, and facts can’t be copyrighted.

THANKS!!

yes — the facts themselves cannot be copyrighted

but the issue of a photo of a 2D versus 3D item seems to come to mind.

one could argue that a photo of a family bible (more than just a flat page)

but a 3D object of the bible — is copyrightable.

but that seems like splitting hairs

I am all for the PUBLIC DOMAIN categorization of family bible records and other similar items – but just wondering what others might try to claim.

It really doesn’t matter what kind of an image it was. Only the image could even be theoretically protected. The data recorded can not be.

I agree – but I am just as much interested in the copyright of the image itself and not just the facts that we know cant be copyrighted,

My original post about photography/scans was really applied to the images and not the facts – which I knew the facts were not copyrightable,

A reminder that nothing anywhere on this website is legal advice. If you really want to know if something is copyrightable or some use might be infringement, you need to consult an attorney licensed to practice in your jurisdiction.

of course – Im just asking the simple question of “Is a scan/photo of a family bible — in the public domain? ” (if the original page/data is in the public domain) – – just a general question.

I know the data (facts) is public domain – is the scan or photo?

My understanding is YES — in most cases it would be in the public domain.

The original question (talking about transcriptions) seemed to be considered a “great copyright question”

so I have no idea why the same question applied to photography would not also be a great question.

Definitely not trying to seek legal advice for a specific legal case.

are there other pages on your site that talk about the subject of photos / scans of 2D images?