Not from the proclamation

It wasn’t the Emancipation Proclamation that freed the enslaved population of the United States.

Oh, that helped, for sure, but it was effective only in the states then in rebellion — in other words, in the Confederacy. The exact language of the proclamation designated as “the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit: Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth)…”1

So as of 1 January 1863, when the proclamation took effect, huge numbers of persons were still held in slavery, including in a number of states ostensibly part of the Union — Maryland, Delaware and Missouri among them.2

No, as The Legal Genealogist noted last year, it was the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution — ratified 154 years ago today — that ended the institution of slavery for once and for all.3

But that doesn’t mean there weren’t free people of color living throughout the United States, and records of their lives and their freedom that we as genealogists can and should seek out. Records that are often stunning in their breadth and scope.

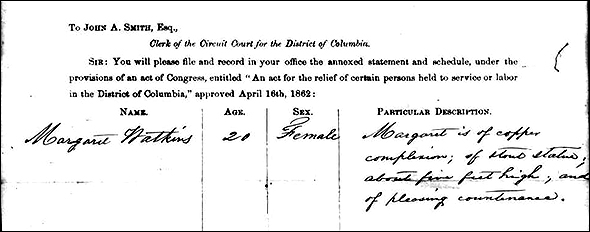

Let’s look at just one example — a set of records close to contemporaneous with the Emancipation Proclamation — from the District of Columbia.

As explained by the National Archives: “On April 16, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed a bill ending slavery in the District of Columbia. Passage of this law came 8 1/2 months before President Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation. The act brought to a conclusion decades of agitation aimed at ending what antislavery advocates called “the national shame” of slavery in the nation’s capital. It provided for immediate emancipation, compensation to former owners who were loyal to the Union of up to $300 for each freed slave, voluntary colonization of former slaves to locations outside the United States, and payments of up to $100 for each person choosing emigration. Over the next 9 months, the Board of Commissioners appointed to administer the act approved 930 petitions, completely or in part, from former owners for the freedom of 2,989 former slaves.”4

Read that again: “930 petitions, completely or in part, from former owners for the freedom of 2,989 former slaves.”

Wow.

And a lot of these records have been digitized and are readily available online.

First, free at FamilySearch is a collection called the “District of Columbia Court and Emancipation Records, 1820-1863,” containing the digitized versions of three National Archives microfilm publications:

• Records of the Board of Commissioners for the Emancipation of Slaves in the District of Columbia, 1862-1863, M520, 4 rolls in Records of the Accounting Officers of the Department of the Treasury, Record Group (RG) 217

• Records of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia relating to slaves, 1851-1863, M433, 2 rolls, Records of the District Courts of the United States, RG 21

• United States Circuit Court (District of Columbia), Habeas Corpus Case Records, 1820-1863, M434, 2 rolls, Records of the District Courts of the United States, RG 21.

Those same records are online at Ancestry as well, for those with an Ancestry subscription or access to a library that subscription to the library edition. The collection “Washington, D.C., Slave Owner Petitions, 1862-1863” has the records from NARA microfilm M520, the collection “Washington, D.C., Slave Emancipation Records, 1851-1863” has the records from NARA microfilm M433, and the collection “Washington D.C., Habeas Corpus Case Records, 1820-1863,” has the records from NARA microfilm M434.

And not as easy to get to but still available free online are the digitized records of the National Archives itself: some 1167 online hits in the National Archives catalog, searching for emancipation records in Record Group 21 and held at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

Want to know more? Check out the great article “Slavery and Emancipation in the Nation’s Capital” by Damani Davis in the NARA magazine Prologue. It’s available online, free, as well.5

No, it wasn’t the Emancipation Proclamation that freed all enslaved persons. But however and wherever emancipation occurred, there are records of freedom just waiting to be found.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “The records of freedom,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 6 Dec 2019).

SOURCES

- “Transcript of the Proclamation,” Online Exhibits > Featured Documents > The Emancipation Proclamation, National Archives (https://www.archives.gov/ : accessed 6 Dec 2019). ↩

- See “Results from the 1860 Census,” The Civil War Home Page (http://www.civil-war.net/ : accessed 6 Dec 2019). ↩

- See generally Judy G. Russell, “Hats off to another amendment,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 6 Dec 2018 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 6 Dec 2019). ↩

- “The District of Columbia Emancipation Act,” Online Exhibits > Featured Documents > The District of Columbia Emancipation Act, National Archives (https://www.archives.gov/ : accessed 6 Dec 2019). ↩

- Damani Davis, “Slavery and Emancipation in the Nation’s Capital,” Prologue (Spring 2010), National Archives (https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/ : accessed 6 Dec 2019). ↩