Researching dower in North Carolina

Reader Marcia is puzzled.

“I have been doing family history in North Carolina and dealing with Dower and other goodies,” she writes. “When she got the land as a dower right did the widow own it outright?”

Great question, because a lot of people don’t understand dower — what it was and how it worked.

First off — the definition.

Dower was the “provision which the law makes for a widow out of the lands or tenements of her husband, for her support and the nurture of her children.”1

So… this is a common-law concept, which means it originated in the English common law we brought over with us as colonists.2

Second — did North Carolina follow the common-law rule?

Oh, yeah. The first reference to dower in colonial North Carolina is in a 1694 court record in which the wife of a landowner relinquished her right to dower.3 The first statute: in 1715, in the context of surveys of land.4 The concept was so ingrained in North Carolina law that, after the Revolution, when the new state was forfeiting lands of British loyalists, it still provided for the dower rights of the widows of men who had been loyal to the Crown.5

Third — does North Carolina still provide for dower today?

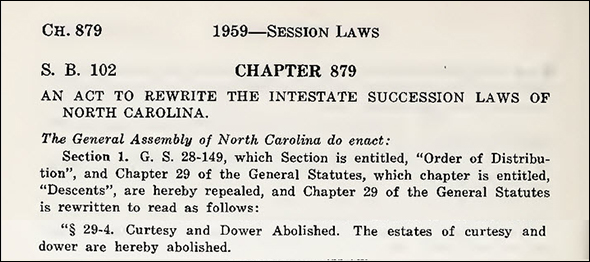

Nope. Dower was abolished in the Laws of 1959, chapter 879, § 1, effective in 1960.6

So Marcia’s research would have to be before 1960 to have dower involved, but note that this only affects widows, not women whose husbands were still alive. So it’s very different from when married women got the right to control their own land. Property rights of married women began to be protected in North Carolina under the Constitution of 1868.7

And finally — what exactly did the widow get?

In general, the widow got “an estate for the life of the widow in a certain portion of the … real estate of her husband, to which she has not relinquished her right during the marriage…”8

And it’s that “estate for the life” part that answers the heart of Marcia’s question: a life estate isn’t the same thing as ownership. It’s defined as an “estate whose duration is limited to the life of the party holding it, or of some other person; a freehold estate, not of inheritance.”9 In essence, the widow had the right to live there the rest of her life (and the dower land usually included the house), farm the land, mine it if it had minerals. It protected her from being out on the street.

But she didn’t own the land and didn’t have the right to pass it on to her heirs. On her death, that one-third would go back into the husband’s estate and get distributed to his heirs. During her lifetime, those heirs could go to court against the widow to stop her from committing what was called waste, like not taking care of the house or chopping down the orchard.

A very different notion from outright ownership.

Tarheel dower: very much a part of researching in North Carolina.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “Tarheel dower,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 25 Aug 2020).

SOURCES

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 393, “dower.” ↩

- See William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England: Book the Second (Of Things) (Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1770), 129 et seq. ↩

- See “Minutes of the General Court of North Carolina, including Chancery Court minutes (Nov 26, 1694 – Nov 30, 1694)”, in William L. Saunders, editor, The Colonial Records of North Carolina, 10 vols. (Raleigh : State Printers, 1886-1890), 1: 434. ↩

- See “An Act for Preventing Disputes concerning Lands already Surveyed,” in Walter Clark, The State Records of North Carolina, 16 vols. (numbered to follow the Colonial Records) (Winston and Goldsboro : State Printer and Nash Brothers, 1895) 23: 36. ↩

- See “An Act to carry into effect … An Act for confiscating the property of all such persons as are inimical to this or the United States…,” in ibid., 24: 268. ↩

- State of North Carolina, 1959 Session Laws and Resolutions (Winston-Salem : p.p., 1959), 886 et seq. ↩

- See Article I, Article X, §4, in North Carolina’s 1868 State Constitution, Secretary of State (https://www.sosnc.gov/ : accessed 25 Aug 2020). ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 393, “dower.” ↩

- Ibid., 720, “life-estate.” ↩

Thanks Judy! Once again, very informative. I do have a question though. Under what conditions did the sale of a property require the wife relinquish her Dower? I see, in NC, a John Doe buying and selling property but only a handful have the second entry from the wife relinquishing her right. What, if anything, can be inferred when the wife does sign versus the properties that do not have her inclusion?

Remember that dower was a right to a life estate in “a certain portion” of the husband’s lands. What that portion was changed after the Revolution. Before a change in the law overturned the straight common-law rules, the widow had a life estate in the lands her husband ever owned. So she’d need to relinquish her rights when he sold it to make sure that clear title was passed. But in 1784, the law changed to limit it only to the lands he owned when he died. (Chapter 22, Laws of July 1784, at p. 35.) So her relinquishment wasn’t required. In 1868, it changed back to the old common-law system, giving her rights in lands he ever owned during the marriage. (Chapter 93, Laws of 1868-69, §§ 32-33, at p. 213.) So after that took effect, relinquishment was required again. What you can infer from the absence of a relinquishment, then, depends on the time period. Before 1784 and after 1868, it might be indirect evidence that the man wasn’t married at the time of the land transaction — but during the 1784-1868 time it could also suggest that the man (or his buyer) came from a place where relinquishment was the norm (like Virginia) and expected it.

Judy,

Thanks for this post and discussion. Nancy Lovelace, my 3x-great-grandmother apparently died in the fall of 1868, after the new Constitution. Her husband Benjamin had died intestate prior to the 1850 census in Rutherford County, NC, where she was listed as head of household with a whole passel of children and grandchildren in the home. I am assuming, especially since I read this post, that Nancy had a life estate in Benjamin’s property. Am I correct? I have a deed from James Lovelace (son of Benjamin and Nancy) and his wife in which they sell their interest in the estate “… of Benjamin Lovelace, deceased, and Nancy Lovelace, late deceased…” in October of 1868 to William Scoggins, who in September 1868 was appointed administrator of the estate of Benjamin Lovelace. The interest is described as “… the one-seventh (1/7) part …” of the estate. What can I infer as to the family makeup of Benjamin and Nancy from this? Can it be inferred that there were seven children? If not, who do the other 6/7ths represent?

You are correct that Nancy had a life estate in the lands Benjamin owned at the time of his death (before 1850). The new Constitution wouldn’t change that after the fact. You are also correct in inferring that there were seven shares in the estate, suggesting that seven children (or their representatives) survived Benjamin and had an entitlement to the estate. So you can infer that, when Benjamin died, there were seven intestate takers and under NC law at the time all children inherited equally and the issue of any deceased child took their parent’s share. It doesn’t mean there couldn’t have been more kids: anyone who’d gotten an advance would be out. But in general, I’d be looking for seven kids alive (or who had already had kids who survived them) when Benjamin died.

Thanks, Judy. That’s the premise I have been working on. It is nice to have confirmation of my theory!

I am curious about what happened when the widow died. Did the husband’s estate have to be re-opened to distribute her dower?

On a slightly related note, if a will gives property to “my dear wife, so long as she remains my widow” what happens when the widow dies? Should the will state specifically what happens then – such as distribute to children or other heirs?

How different are dower “rules” from state to state?

Thanks for your insights.

Thank you for explaining this. My ancestor Juliatha Hunt was left the estate of her husband David until her death at which time the estate would be divided among the grandkids. So would there be a record of the estate being divided after Juliatha’s death? And would that be in Court records such as Plea records. I get a bit confused as to which Court documents I should look at. Need to know where to look for that information. Using what I can find on Family Search and in books.

What happens if the widow remarries? I would assume that she relinquishes her dower rights, but I cannot find anything that specifically states that.

It would depend on time and place but, at common law, no, remarriage did not relinquish dower rights. There are many cases where the suit to claim dower is actually brought by the second husband in right of his wife.