Case filed in California

Where’s the line between making material available for genealogical research, and using private data for commercial gain?

A lawsuit filed in federal court in San Francisco on Monday may help define the answer to that question.

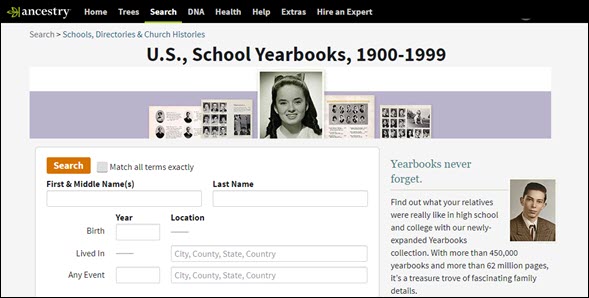

The case, brought by two California residents against Ancestry, focuses on the yearbook collection — “U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999” — and charges Ancestry with “knowingly misappropriating the photographs, likenesses, names, and identities of Plaintiffs and the class; knowingly using those photographs, likenesses, names, and identities for the commercial purpose of selling access to them in Ancestry products and services; and knowingly using those photographs, likenesses, names, and identities to advertise, sell, and solicit purchases of Ancestry services and products; without obtaining prior consent from Plaintiffs and the class.”1

The suit goes on to claim that:

• “The names, photographs, cities of residence, schools attended, estimated ages, likenesses, and identities contained in the Ancestry Yearbook Database uniquely identify specific individuals.”2

• “Ancestry is knowingly using the names, photographs, and likenesses of Plaintiffs and the class to advertise, sell, and solicit the purchase of its subscription products and services.”3

• “Ancestry appropriated and continues to grow its massive databases of personal information, including its Ancestry Yearbook Database, which contains the names, photographs, cities of residence, schools attended, estimated ages, likenesses, and identities of tens of millions of Californians. Ancestry uses these records both as the core element of its products and services, and to sell and advertise its products and services, without providing any notice to the human beings who are its subjects. Ancestry did not ask the consent of the people whose personal information and photographs it profits from. Nor has it offered them any compensation for the ongoing use of their names, photographs, likenesses, and identities as part of its products and services, and to sell and advertise its products and services.”4

And this conduct, the suit alleges, violates a whole bunch of California statutes: “the California right to publicity as codified in Cal. Civ. Code § 3344; the California Unfair Competition Law, Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 17200 et seq.; California’s common law right protecting against Intrusion upon Seclusion; and California Unjust Enrichment law.”5

Both plaintiffs are included in the yearbook database:

Plaintiff Lawrence Geoffrey Abraham asserted three records and claimed that “The three records corresponding to Mr. Abraham uniquely identify Mr. Abraham. All three plainly and conspicuously display Mr. Abraham’s name, image, photograph, estimated age, school, city of residence, and the date of the yearbook in which the photo appears. In two of the records Mr. Abraham’s face is the sole subject of the photograph. One of the records identifies school participation in the school track team.”6

Plaintiff Meredith Callahan asserted that the database included 26 records that “uniquely identify Ms. Callahan. All plainly and conspicuously display Ms. Callahan’s name, image, photograph, estimated age, school, city of residence, and the date of the yearbook in which the photo appears. In four of the records Ms. Callahan’s face is the sole subject of the photograph. In all twenty-six records she is clearly identifiable by name and image. Various of the records identify Ms. Callahan’s school participation in student council, cross country running, track, “Students Against Drunk Driving, “Quiz Bowl,” the National Honors Society, and ski club. One record identifies her as a valedictorian of her senior class.”7

The essential argument the lawsuit makes it that “Ancestry did not and does not seek consent from, give notice to, or provide compensation to Plaintiffs and the class before placing their personal information in its Ancestry Yearbook Database, selling that information as part of its subscription products, and using that information to sell, advertise, and solicit the purchase of its subscription products.”8

The case is filed as a prospective class action. That means, if the court permits it, these two plaintiffs will be allowed to represent the entire class of people who are California residents, included in the database, and who didn’t give permission for their images to be included in the database.

And the relief sought is a permanent order barring the use of the images plus damages and attorneys’ fees.

So… what’s the outlook here?

No clue.

The dividing line between the right of personal privacy for living people and access to information that is generally available is fuzzy at best, and a constantly moving target as online access to data and information continues to grow and expand.

We just don’t know, right now, whether a yearbook you can view and even copy at a library in the town where the school was located can be legally digitized, put online and — part of the complaint in this case — used as a teaser for a commercial service.

We don’t know, as yet, whether the law gives someone like these plaintiffs the right to complain if — say — the same yearbook was digitized and put online by the school itself.

So the case offers the first real opportunity to see where the line will be drawn — at least under the generally more-restrictive privacy laws of California — and whether those California laws will control access to information beyond California’s borders.

Stay tuned.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “Ancestry sued for yearbooks,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 2 Dec 2020).

SOURCES

Aren’t these yearbooks considered copyrighted? Therefore, only yearbooks published in 1924 and before would be fair game until next year, when they add 1925.

All the ones I’ve looked at were published without any copyright notice; any like that up to a certain date (1978?) I think are not under copyright.

There are two operative dates: before 1978 without notice, never copyrighted. Between 1978 and 1 March 1989, the lack of notice could be cured by registration within five years of publication.

That’s an “it depends” question, I’m afraid. Before 1977, the yearbook would have had to have a copyright notice and be registered with the Copyright Office or it would have been out of copyright at the moment of publication. That registration was only for 28 years but could be renewed. So even those initially copyrighted might now be out of copyright. And there are a whole host of other variables until the 1976 copyright act kicked in and neither notice nor registration would be required going forward.

Thank you for your explanation.

I think the monetary gain of photo’s of people who did not give consent, it going to be a big hurdle in this case.

Everyone is talking about all these different timelines that the article isn’t even about. The article is about the yearbooks in the 90’s.

Unfortunately I think they are considered public record information.

De, the years in question are 1900-1999, not just the 90s.

Both Ancestry and FamilySearch have an image of my father’s obituary in their databases. I wrote it. I own the copyright to it. They both probably have tens of thousands of such copyrighted images on their websites.

if you never purchased a copyright on you do not own the copyright

NOT true — and this is not a copyright case.

You do NOT need to purchase a copyright on something like an obit. I have even published a book without purchasing a copyright. I did send myself a copy of the book before publishing it for sale. It is called “poor man’s copyright” and it is legal.

It’s correct that you don’t need to register your copyright in order to have copyright protection (nobody buys a copyright unless you’re buying it from the original creator of the work). However, let’s forever drive a stake through the heart of the myth that sending a copy of a work to yourself does anything at all to protect your rights. It does not. It is NOT any kind of legal protection at all. To quote the U.S. Copyright Office, “The practice of sending a copy of your own work to yourself is sometimes called a “poor man’s copyright.” There is no provision in the copyright law regarding any such type of protection, and it is not a substitute for registration.”

Earlier this year, in lockdown, I decided to google some old friends to see how they were doing and possibly reforge some connections. Sadly, I found far too many obits. One was for a long-ago girlfriend whom I remembered fondly and would have dearly loved to talk to again; alas, she had died more than 10 years ago.

I added her to a “personal memorials” tree on Ancestry.com and in the course of searching I found her yearbook. Not just “the book for her year”; the yearbook that she had owned in her senior year, with all the signatures and messages written by her friends! I did not know her at that time of her life, so that was a very special find, and I am sad and happy to have it; her “senior saying” was especially poignant.

The odds are low, but surely other Ancestry.com users may have a similar experience, of finding a yearbook with notes to and from people that they knew.

At the time I thought about why Ancestry.com was able to create this database of digitized yearbooks. Looking at my ex-gf’s yearbook images, and also my own (all from the early 1970s) I saw that none of them had a copyright statement… which I suppose was the case because, who could say who owned it? So, at least up to a certain point, I think these books are fair game for copying, up to a certain year anyway.

But in the context of this lawsuit I think there may be more issues. Don’t the people who wrote those notes own copyright in them?

There are so many “it depends” situations here and I think we’re just going to have to await court decisions on them.

Classmates.com also has a lot of yearbooks on their site. I no longer have a paid subscription but I have seen many listed there.

Classmates is not part of this lawsuit.

I wonder how this case might affect other yearbook collections, such as the one on MyHeritage or even those held in the digital collections of libraries and archives. I suppose only time will tell.

Exactly: only time will tell.

How is this really any different than say Classmates.com where you can view yearbook photos (many of the same as on Ancestry or MyHeritage). Classmates also charges money. Seems to me that people don’t mind older records online, but maybe newer(ish) stuff they are against. Maybe these people are just mad and don’t like their yearbook photos or that you can see they were in band. lol (that’s a joke for those without a sense of humor).

I know there is a fine line sometimes between privacy and what not. But this seems a little silly to me.

The essential difference at the moment is who got sued. 🙂

Ancestry is notorious for taking free information, and charging for it. Without perission. That could very well be why the lawsuit originated. Other sites may have permisson from the owners of the material.

Classmates.com also has oodles of yearbooks imaged online–and keeps trying to sell me reprints of my high school yearbooks. Obviously Classmates doesn’t have the TV commercial presence Ancestry has. It will be interesting to see how this will play out.

Not relevant. The lawsuit is against Ancestry. It doesn’t matter what anyone else does, for the purpose of this case.

I agree, Judy, it’s not relevant—to this case. But the vultures will most assuredly come after Classmates.com, after they’ve picked the bones of Ancestry. As a genealogist, it’s very relevant to me.

ALL records access is relevant to genealogists.

It will be interesting to see how it plays out. You would think the yearbook or photographer of the pictures would have the right to sue. Not the person in the photo. A yearbook to me really doesnt give out much living info unless you have alot of facts.

The case alleges invasion of privacy and misappropriation of image. That claim can ONLY be brought by the person in the photo.

Jeff, one of the possible security password reset questions on many websites is “What school did you attend when you were 13?” If someone has a copy of my high school yearbook and knows anything about my hometown, they would have TWO choices that would be the correct answer for 99% of the people in my yearbook. That is just one of the implications.

I am commenting from the other side of the Atlantic, where our law differs from yours quite a bit; and I’m no lawyer. But the plaintiffs agreed to have their photos, names and details published and be put out into public view – otherwise they wouldn’t be in the yearbook. They clearly didn’t agree to Ancestry or anyone else publishing them, but as the yearbook is clearly in public I can’t see much of a case on commonsense grounds. Their hometown newspapers will have published photos too, with stories of these folks going off to college, daughter and son of Mr and Mrs Parent who are so proud of them and who run the general store…. all this has also always been out there for the public to see.

I think on balance I rather hope they lose.

The issue is commercial misappropriation of the image, that is “you used my image to sell your product.” That’s different than merely making it available in a library.

The students in yearbooks, are minors, therefore they could not legally give permission. And, their parents did not give permission for Ancestry to sell the images, which it is in essence, doing.

Anyone who was in high school in 1999 is an adult now. Parental consent is irrelevant.

Judy, IF the parents HAD given consent, as I had to do for my children, starting in about 2001 when they attended summer day camps or any school (part of the start of school year paperwork), then the children are probably not given the right to revoke that consent. If they were, it would create a nightmare if the chess camp where the pictures were taken uses Hunter’s photo on their website, and five years later, when he is an adult, he tries to revoke that permission. Model release forms are irrevocable, so I’d think these forms would be written similarly. I don’t have one available to check.

I agree, yearbooks are pretty much in the public arena, anyone can buy a copy of any yearbook through classmates.com.

It has got to be a breach of copyright. Every author has copyright, whether they claim it or not, and so does the publisher.

I think these yearbooks are peculiar to America, one of the odd high school customs that has developed like “prom” and “homecoming” and “valedictorian”

Legally wrong. First, THIS ISN’T A COPYRIGHT CASE. I keep saying that. It’s a privacy – misappropriation of image case. Copyright is NOT INVOLVED.

Second, anything published in the US before 1925 (and, soon, 1926) is out of copyright, period. Between then and 1989, there are variables in play that could mean many if not most of these publications are out of copyright. So a whopping big percentage of these yearbooks likely have NO copyright issue anyway, even if this was a copyright case, which it is NOT.

Judy, I’m wondering if newspapers will be next in line after this case is settled. Ancestry offers Newspapers.com. Newspapers have pictures with identifying names, ages, and places—definitely used to sell product. Wow. This will be interesting. Thanks for bringing this case to our attention.

There are all kinds of possible scenarios — we’ll just have to see how this plays out.

What does “to advertise, sell, and solicit purchases of Ancestry services and products” mean? Is Ancestry using the data to target potential customers individually? Or are they just saying, “We’ve got lots of yearbooks — sign up and see if you get lucky!” My yearbooks are on their site and I’ve never been approached commercially. Seems a tough job to find email addresses for folks recorded 50 years before email. I don’t see the plaintiffs’ case unless maybe they’ve received marketing based specifically on their appearance in an archived yearbook. It’s also a weak marketing ploy when anyone can go to a local library that subscribes just to check for this one thing. So is it targeted or broadcast advertising?

That’ll be for the courts to decide.

Everyone has to sue someone for something. Get over it! We’re you really injured? No! Do you really think Ancestry made that much money from having yearbooks added to their vast database of information? No! That really isn’t much help when you are looking up genealogy, at least anyone who is still alive. So I say they need to get over themselves and live their little lives in California where there are way too many laws anyway!

If memory serves me the publisher of the yearbooks owns the images and data in the books so if they gave permission to use there contents its irrelevant what the people in the yearbooks say about it. And if someone bought the publisher they could do what they want with there books including put them on the internet. Kinda like Google sells access to peoples stuff everyday to marketing companies. And I don’t see anyone seeing them.

You might want to read the complaint and the California law.

Copyright doesn’t come into play here. I was editor of my high school yearbook. We students, with help from the faculty adviser wrote and placed everything in it. The company that took the school pictures provided the official school pictures. All other pictures were given to us by either the school or the person who took them. There were no releases or restrictions asked for or received, because no one even thought of it. Since we students submitted them to the printer, I guess that made us the publisher as well. The yearbooks were sold to the students, No one had even dreamed of the internet yet, and the idea of using the yearbook for anything other than a personal memento would not have occurred to anyone involved. The only question in the court is whether this was a private or public use of the contents. I might have had mixed feelings a few years ago. Today, I have reached the conclusion that personal privacy is an illusion. And in a few generations, even the illusion may disappear.

Judy,

As some people seem to be confused about which law forms the basis of this complaint, perhaps it is worth quoting he salient part of the California Civil Code section 3344:

“(a) Any person who knowingly uses another’s name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness, in any manner, on or in products, merchandise, or goods, or for purposes of advertising or selling, or soliciting purchases of, products, merchandise, goods or services, without such person’s prior consent, or, in the case of a minor, the prior consent of his parent or legal guardian, shall be liable for any damages sustained by the person or persons injured as a result thereof.”

Source: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?sectionNum=3344.&lawCode=CIV

Thanks. It won’t help those who reaaaaalllly want this to be about copyright, but…

So in reply to Andy, using the images ON the Ancestry website is ok, but using the images BY Ancestry for marketing, advertising etc is what they are suing over?

I am curious as to what “injured as a result” means. How would you prove you were injured because your yearbook is published? My hometown has a newspaper column where they post pictures from the past and they don’t ask for permission. I have been in it for something I did in grade school and I only know because some of my friends sent it to me. I live out of the country where I was born and raised. I have no interest in suing them but I was just curious about how they can prove they have been injured or harmed by the yearbook being published.

Will the plaintiffs have to prove that Ancestry made money off the yearbook being available in order to win? This is quite interesting.

The notion of injury in law is a complex one. We’ll have to see how this plays out.

I’m thinking a recognizable someone with a ‘bad hair’ photo was angry that they have been used as advertising and had some sort of fallout at work or home. Or perhaps they are in the military and using their likeness puts them in a complicated position. I know I wouldn’t want some of my yearbook photos on a national ad campaign without some sort of warning and maybe a free subscription. Not everyone wants their 90 seconds of fame.

Ancestry has been getting like a personal information devouring octopus. I think someone with a legal degree should be taking a look at the companies changing practices and raising suits like this. The amount of information they are siphoning on deceased individuals in closed private trees and sending out t info out to other users is alarming. If they are not sending them your year book photo, it’s your parents obits, that you clipped from Newspapers and saved to your locked private tree, it’s now sucked up your parents locations of burial and their causes of death from that private tree. I wondered if the yearbook pictures shown to the world. So happy to see that someone is looking at the nuances. as I would think there are probably a lot of people who also would prefer not to see the note they wrote in someone else’s yearbook published in a public format, those should be air brushed out. There appears to be a real battle between your right to know, and my right to some personal family privacy. And we are all loosing it. I wish every state had the personal privacy protections CA and the UK do. You should be able to ask Find a Grave to take a burial location down, that a stranger posted for your parents. They have turned Find a Grave into a game for sweet people with too much time on their hands. So they have this massive band of well intentioned individuals scurrying around for free to upload as many obituaries and grave locations as they can. Someday that massive data base will bring in quite a bit to Ancestry when they sell it. For every person that finds grave info there and is pleased, there are likely 6 more

people who feel invaded and who consider it private information, only the immediate family should know. Ancestry has gotten way too big for my comfort level. There are many things I’d like to know, that are none of my business, like what my Mom’s 1st boyfriend looked like, but I think I am willing to sacrifice my curiosity, so that someone else does not have to have an un flattering picture of them out there in Ancestry’s year book collection. My “right” to know should not supersede other people’s privacy, especially if their DNA might also be held by the same company. It’s a scary comb. The only people who have a right to that kind of info are immediate family in my opinion. I recently found a cousin who is in her 50’s entire marriage license including parents names, dates and places of births on the site. These are living people. I think the company needs to show some sense about what it is extracting from private tresses and what it is posting. Perhaps they could allow people to cover their entries if they don’t want them showing in the year book collection, or take down pieces of info people don’t want displayed.

Marge, where you said “I wish every state had the personal privacy protections CA and the UK do”, I think it worth picking out some of the detail. The Californian Civil Code Section 3344 is what is referred to as publicity right legislation (arguably it’s one of the most comprehensive in the world). That is altogether different to privacy legislation. And while the UK has both statutory and uncodified common law protections around the use of personal data and an individual’s private and family life, we don’t have any specific statutory protection for the publicity right. At best, an individual in the UK who has some celebrity status may be able to bring an action for passing off if their image is used in a way which implies that they are endorsing or promoting a product (ie pretty much what is being claimed in the Ancestry case Judy has written about). But that route would not work for an erstwhile high school or college grad in the UK because they would lack an essential ingredient, namely any goodwill attached to their persona. The CA law provides this protection for all of its citizens, even though the law was initially brought about to protect Hollywood stars.

You seem to be advocating better legal protection for the way the personal data of American citizens can be processed, perhaps along the lines of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation. All I can say is, be careful what you wish for. In any case, given that the vast majority of corporations which thrive on amassing, storing and sharing private data are American, I imagine that Congress would face an almost insuperable amount of lobbying against such legislation as this would severely impact major revenue streams for the likes of Google, Facebook or Ancestry, to name but three out of dozens of such companies.

I don’t remember having ever consented to having my photo published in a school yearbook.

Of course, as a minor for most of those years (the age of majority then was 21), had I been asked my consent would have meant nothing.

Case update: Ancestry.com filed a motion to dismiss the complaint on 4 Jan 2021, and all parties have exchanged opposition and reply briefs. A hearing on the motion was scheduled for 18 Feb 2021 but the online source for the docket is not current and I no longer have free Pacer service since I retired at the end of last month. Perhaps TLG can check to see if the court ruled yet.

PACER is essentially free for anyone — you get up to $30 in usage every quarter for no cost. As of today: “Given the pending motion, the court continues the CMC until 5/27/2021 at 11:00 AM in San Francisco, Courtroom B, 15th Floor. Case Management Statement due by 5/20/2021.”

The case was dismissed.

I’m not sure why you’re posting a response in August to a comment posted in February, especially since the dismissal of the case was fully reported in June (see https://www.legalgenealogist.com/2021/06/17/case-closed/).