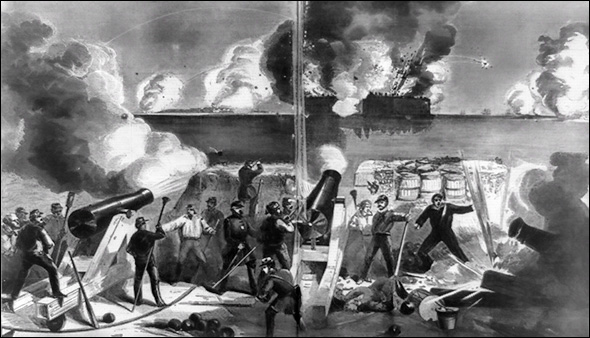

The bombardment of Fort Sumter

There was no question but that war would come.

The only question, really, was when.

By the beginning of April of 1861, seven southern states had already passed ordinances of secession — South Carolina was first on 29 December 1860, followed by Mississippi on 9 January 1861, then Florida on 10 January, Alabama on 11 January, Georgia on 19 January, Louisiana on 26 January and Texas on 1 February.1 Southern delegates convened in Alabama on 4 February 1861 and established the Confederate States of America, which proceeded to seize federal forts within its borders.2

And sitting right in the middle of the hotbed of secession, in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, a Union fortress.

Fort Sumter.

It had been built, initially, as part of a plan of coastal fortification that followed the War of 1812. As explained by the National Park Service:

Since the American Revolution, Americans have built systems of forts at harbors along the coast to strengthen maritime defenses. Following the War of 1812, several major weaknesses in the American coastal defense system were identified. To fill these voids, Congress and the US Army Corps of Engineers planned the construction of around 200 fortifications, primarily located along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts from Maine to Louisiana. Over 40 fortifications were built before construction halted with the outbreak of the American Civil War. These forts are collectively known as the Third System of Seacoast Defense. Charleston Harbor made the list of sites vulnerable to attack, prompting the construction of Fort Sumter. Construction on the man-made island began in 1829.3

The troops on Fort Sumter hadn’t started there. Initially, they’d been at Fort Moultrie, a brick fort on Sullivan’s Island built as part of a second seacoast defense system and completed by 1809.4 A small garrison under U.S. Army Major Robert Anderson, who’d been ordered to take command in November 1860, made the move to Fort Sumter late in December 1860, a move that enraged the Confederates:

In Charleston, the birthplace of secession, tempers are on edge. A delegation from the state goes to Washington, D.C., demanding the surrender of the Federal military installations in the new “independent republic of South Carolina.” President James Buchanan refuses to comply. Charleston is the Confederacy’s most important port on the Southeast coast. The harbor is defended by three federal forts: Sumter; Castle Pinckney, one mile off the city’s Battery; and heavily armed Fort Moultrie, on Sullivan’s Island. Major Anderson’s command is based at Fort Moultrie, but with its guns pointed out to sea, it cannot defend a land attack. On December 26, Charlestonians awake to discover that Anderson and his tiny garrison of 90 men have slipped away from Fort Moultrie to the more defensible Fort Sumter. For secessionists, Anderson’s move is, as one Charlestonian wrote to a friend, “like casting a spark into a magazine”.5

The new Confederate government ordered its commander in South Carolina, General P.G.T. Beauregard, to take Fort Sumter. Beauregard sent his aides to demand the Fort’s surrender, and Anderson refused. And so, at 4:30 a.m. on 12 April 1861, it began: the shelling of Fort Sumter by Confederate forces. The exchange of cannon fire lasted for 36 hours until the Union troops ran out of supplies and had no alternative but to surrender.6

The opening battle of the Civil War. The initial act of four years of bloodshed and loss.

And for genealogists the start of an era that would result in an explosion of records to use in family history.

That’s always the kicker for us, isn’t it? Things that are absolutely awful for those who lived through them, from wars to natural disasters to public health crises — these are the things that created records for us. Our city-dwelling non-property-owning tenant laborer ancestor might have left no record at all, if he hadn’t died in a plague, or been recorded in the coroner’s book after an earthquake, or been required to register for the draft and sent off to war.

As researchers, we’re always torn between the awful realities of the human cost of those times and the appreciation of the records that we wouldn’t have if the times hadn’t been so awful.

We can’t help but treasure the amazing array of military and civilian records that resulted from the Civil War: enlistments, draft records, service records, tax records, provost marshal records, pensions and more. There isn’t a family that can trace its roots back to this time that cannot find at least one record that simply wouldn’t exist but for the war. Records of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Records of the Southern Claims Commission. 1867 voter registrations of southern men. Draft registers in northern cities and towns. The beginning of the homesteader movement and its records. So many things we now use routinely for family history.

And yet we need to acknowledge the records losses as well. For those like The Legal Genealogist, with roots deep in Virginia, we can’t help but mourn the horrific losses of historical records when Richmond — capitol of Virginia and capitol of the Confederacy — was burned by Confederates in the last desperate days of the war in 1865. So many county clerks had carefully boxed up their records and sent them to Richmond for safekeeping… and they were nothing but ashes when the smoke cleared in April of 1865.7

Another branch of my family was in North Carolina and was heavily involved in the early settlement of Burke County. It isn’t entirely clear who did what — the stories range from the Confederates chasing the Union troops into the courthouse and setting it on fire to smoke them out to the Union troops chasing the Confederates into the courthouse and setting it on fire to smoke them out — but what is clear is that there are no surviving deeds, probates or other critical records that survive to today.8

For others, the issue can be records that simply never were created. Look, for example, at the court records of Calhoun County, West Virginia. The minutes of the County Court there record the adjournment of the May term 1861 — and the next entry is the September term 1865.9 Split horrifically between Union and Confederate sympathizers, the government there simply ceased functioning.

There have been and will continue to be many opportunities for every American to consider the human costs of the Civil War.

For us, as researchers, we’ll leaven our dismay over those human costs with the joy of the records we gained.

But let’s take a moment — here on this 160th anniversary of the bombardment of Fort Sumter — to think as well of the records that were lost.

On this day when we think back on that war.

And how it began.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “And how it began…,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 12 Apr 2021).

SOURCES

Image: “Bombardment of Fort Sumter by the batteries of the Confederate states,” Harper’s Weekly, 27 Apr 1861; Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division.

- “Dates of Secession,” American Civil War, Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Georgia (https://www.libs.uga.edu/hargrett/ : accessed 12 Apr 2021). ↩

- See Library of Congress > Digital Collections > Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints > Articles and Essays > “Time Line of the Civil War 1861,” LOC.gov (https://www.loc.gov/ : accessed 12 Apr 2021). ↩

- Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie National Historical Park > Learn About the Park > History & Culture > Places > “Fort Sumter,” NPS.gov (https://www.nps.gov/ : accessed 12 Apr 2021). ↩

- Ibid., “Fort Moultrie.” ↩

- “,” American Battlefield Trust (https://www.battlefields.org/ : accessed 12 Apr 2021). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- See generally Judy G. Russell, “When Richmond fell,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 3 Apr 2015 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 12 Apr 2021). ↩

- Burke County takes the official position that it was the Yankees who were at fault. See “History of the County,” Burke County, NC (https://www.burkenc.org/ : accessed 12 Apr 2021). ↩

- Calhoun County (West Virginia) County Court Minutes, 1: 135-137; Circuit Court Clerk, Grantsville; digital images, “Minutes, 1856-1877,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 12 Apr 2021). ↩

I can not imagine what was going through the mind’s of those men. Firing upon fellow Americans, the Constitution broken down the middle. Incredibly brave men fighting to the last breath! At first it is for what you believe in, later it is just trying to stay alive.