Ancestry wins yearbook lawsuit

A lawsuit claiming that Ancestry was causing legal injury by posting yearbook photos on its website and using them in advertising and promotional materials has been thrown out by a California federal court.

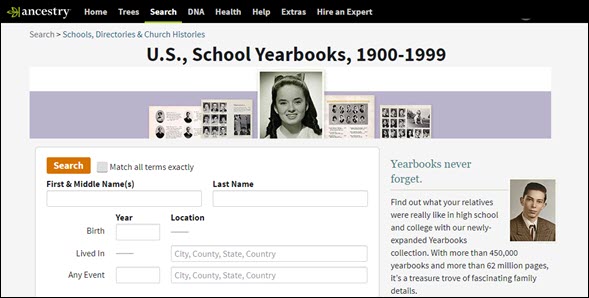

The case, brought in late 2020 by two California residents against Ancestry, focused on the yearbook collection — “U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999” — and charges Ancestry with “knowingly misappropriating the photographs, likenesses, names, and identities of Plaintiffs and the class; knowingly using those photographs, likenesses, names, and identities for the commercial purpose of selling access to them in Ancestry products and services; and knowingly using those photographs, likenesses, names, and identities to advertise, sell, and solicit purchases of Ancestry services and products; without obtaining prior consent from Plaintiffs and the class.”1

The plaintiffs, both included in the yearbooks database, brought the case as a possible class action for all persons. They argued that Ancestry was “knowingly using the names, photographs, and likenesses of Plaintiffs and the class to advertise, sell, and solicit the purchase of its subscription products and services”2 and without telling them, asking for consent or paying them.3 That conduct, they claimed, violated a whole bunch of California statutes: “the California right to publicity as codified in Cal. Civ. Code § 3344; the California Unfair Competition Law, Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 17200 et seq.; California’s common law right protecting against Intrusion upon Seclusion; and California Unjust Enrichment law.”4

Federal Magistrate Judge Laurel Beeler disagreed, ruling on Tuesday that the plaintiffs didn’t suffer any kind of legal injury and, so, didn’t have a right to sue Ancestry. She concluded that Ancestry’s use of the photos didn’t cause any financial harm, wasn’t defamatory in any way and didn’t pose any credible risk of future harm.5

Magistrate Judge Beeler also ruled that Ancestry was immune from suit under the federal Communications Decency Act, 47 U.S.C. § 230(c)(1), because all it did was act as a content publisher, not a content creator.6

The decision came on a motion that focused solely on the legal basis for the lawsuit. A motion brought by a defendant like Ancestry to dismiss at this stage basically argues that it doesn’t matter what the facts might be at a trial, the law wouldn’t allow a judgment on these claims anyway. In essence, the judge agreed that no proofs at trial could change the outcome: the law was on Ancestry’s side.

The ruling came after the judge had already ruled once that the claims were legally insufficient, and had already given the plaintiffs a chance to revise their complaint to meet the insufficiencies. Because “the plaintiffs did not cure the complaint’s deficiencies” the order dismissing the case was with prejudice.7 In other words, they can’t come back to the same court with the same complaint — the only option now is to try to convince an appeals court this ruling is wrong.

All of which means — in plain terms — case closed.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “Case closed,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 17 June 2021).

SOURCES

- ¶ 2, Complaint, Callahan et al. v. Ancestry, Case no. 3:20-cv-8437, U.S. District Court, Northern District of California, filed 30 Nov 2020. ↩

- Ibid., ¶ 8. ↩

- Ibid., ¶ 13. ↩

- Ibid., ¶ 14. ↩

- Order Dismissing First Amended Complaint, Callahan et al. v. Ancestry, Case no. 3:20-cv-8437, U.S. District Court, Northern District of California, filed 15 June 2021, slip op. at 5-9. ↩

- Ibid. at 9-12. ↩

- Ibid. at 12. ↩

Thank you for following this. I’d been curious about the outcome, especially since so many of the yearbooks are more current and have living people. That doesn’t mean I haven’t used them, though. 🙂

Seeing my own picture (misidentified) was a little disconcerting; however, I suppose it’s not much different than a picture in a newspaper.

That phrase about lack of “legal injury” is intriguing. If a genealogy is published as a non-profit undertaking, how is publishing photos normally subject to copyright much different?

Two different concepts of injury: legal injury in the copyright sense is different from the legal injury to reputation or privacy.

I would be really interested to know if this would also apply in Canadian law. We hoped to be able to put the local yearbooks up on our genealogy club website but don’t want to get into a legal hassle.

This particular decision wouldn’t have any relevance in Canada — you’d have to consult with an attorney licensed there to be sure.