Repeating the mantra

Those who’ve heard The Legal Genealogist speak about the law and genealogy have heard the mantra.

Those who’ve followed this blog for any length of time have read the mantra.

Feel free to chant along with me out loud:

If we want to understand the records, we have to understand the law.

And then, of course, comes the key element: it’s not just the law in general, but the law at the time that particular record was created and in the place where that particular record was created.

And a question that came in on the blog yesterday is the perfect case in point.

Reader Angela has a 1768 North Carolina deed where the seller identified himself as the “rightful owner of the land in fee simple,” and, she noted, “his is the only name in the body of the deed.” From her research into the family, she thought the seller was “the eldest son who inherited it outright” from his father under the inheritance rule called primogeniture, under which all land automatically went to the oldest son if there wasn’t a will that said otherwise.1

What she wasn’t quite sure of was the two other names that appear on the deed. One was a woman’s name, just under the seller’s name, and the other was a woman who signed in a relinquishment of dower — that formal way that a woman entitled to dower in land would give up her interest. Dower, remember, is “the provision which the law makes for a widow out of the lands or tenements of her husband, … an estate for the life of the widow in a certain portion of the … real estate of her husband…”2 She usually got a life estate in one third of the lands, so it’s often called the “widow’s thirds.”

Angela wanted to figure out who these two women were. “My thoughts,” she said, “would be the woman who signed and went into court separately was his mother and maybe the one who signed under him was his wife? Does this sound probable?”

It’s a pretty safe bet that the two women are indeed the wife and the mother.

What’s not such a safe bet is which one is which.

And the reason is a matter of time and place.

Particularly in North Carolina, and particularly at this time, when the law was beginning to change.

By 1784, primogeniture would no longer be the law in the Tarheel State.3

At the same time, the law changed with respect to dower, away from the old common law rule of dower in all the lands the husband ever owned to a new rule of dower only in the lands the husband owned at the time of his death.4 It didn’t change back to the common law rule until 1868 so, for the most part, those formal relinquishments disappeared in North Carolina from 1784 to 1868.5

But, right at this time, when this deed was being signed, in this place, in North Carolina, the law was clear:

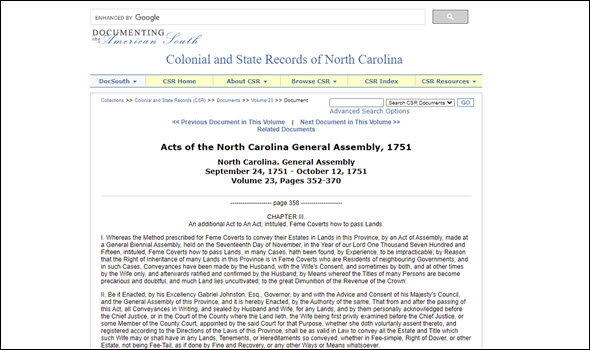

That from and after the passing of this Act, all Conveyances in Writing, and sealed by Husband and Wife, for any Lands, and by them personally acknowledged before the Chief Justice, or in the Court of the County where the Land lieth, the Wife being first privily examined before the Chief Justice, or some Member of the County Court, appointed by the said Court for that Purpose, whether she doth voluntarily assent thereto, and registered according to the Directions of the Laws of this Province, shall be as valid in Law to convey all the Estate and Title which such Wife may or shall have in any Lands, Tenements, or Hereditaments so conveyed, whether in Fee-simple, Right of Dower, or other Estate, not being Fee-Tail, as if done by Fine and Recovery, or any other Ways or Means whatsoever.6

In other words, it was the wife who had to be “first privily examined … whether she doth voluntarily assent” to the sale of any land her husband owned and was selling, in order to clear the buyer’s title from any claim by the wife later to dower.

So let’s think about this deed again. If Angela is right, and the seller is the oldest son who inherited this land, his mother would have had an already-existing life estate in one-third of that land — that’s her dower. Her life estate began automatically on the death of her husband, the seller’s father. So yes, the son owned the land in fee simple, but subject to his mother’s life estate.

In essence, the seller and his mother jointly owned all the then-existing rights in the land and, signing together, they could sell all the rights in the land as of that moment.

But the wife had this potential future interest, her dower right that would come about if she outlived her seller-husband. And the law said she had to be “first privily examined … whether she doth voluntarily assent” to giving up that potential future interest.

At this time and in this place, then, it’s more likely that the woman who signed just beneath the seller was the mother, selling her current life interest the way her son was selling his current fee simple interest, and the woman executing the formal relinquishment of dower was the wife.

Because that’s what the law at that time and in that place required.

This is why it’s my mantra: If we want to understand the records, we have to understand the law.

And not the law in general. It’s the law at that time in that place that we need to look at.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “Time and place,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 8 Feb 2022).

SOURCES

- See Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 937, “primogeniture.” ↩

- Ibid., 393, “dower.” ↩

- “An act to regulate the descent of real estates, to do away entails, to make provision for widows, and to prevent frauds in the execution of last wills and testaments,” Chapter 22, North Carolina Laws of April 1784, PDF online, North Carolina Digital Collections (https://digital.ncdcr.gov/ : accessed 8 Feb 2022). ↩

- Ibid., §VII. ↩

- See generally Judy G. Russell, “More on dower,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 27 Aug 2020 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 8 Feb 2022). ↩

- “An additional Act to An Act, intituled, Feme Coverts how to pass Lands,” North Carolina Laws of 1751, chapter 3, in Walter Clark, compiler, State Records of North Carolina, Vol. 23 (Goldsboro, N.C. : Nash Brothers, Printer, 1904), 358-359; online version, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South (https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/ : accessed 8 Feb 2022). ↩

Thank you so much, Judy! This is something I have gone back and forth on and wanted to get right (as right as we can be in these situations) I had read your previous articles and read the NC laws – so was confident I knew the laws, just not sure how to determine which woman was which.

Thank you for a great question!!

Ah, you have the jump on us with your law degree. I read this, then read it again just to see if I could understand it a little better. Yes, second slow read was a little better. But hold this column. If I’m still kickin a year from now, might just have to take another look/

You better be kicking a year from now… I’m planning on coming back to Texas and we really need to get together, cousin.