… a copyright follow-up …

The Legal Genealogist has been patiently waiting for the question to be posed.

It was only a matter of time, though I will confess that it’s taken a lot longer than I thought it would.

But yesterday was the day.

After yesterday’s post about copyright, reader Matthew Shaffer finally asked, in essence, why I keep stressing that copyright expires at a particular time as to things that are legally or lawfully published in the United States.1

“As anything legally published in the United States before 1927 is no longer in copyright,” he wrote, “if something were to have been ‘illegally’ published before 1927, would copyright not apply?”2

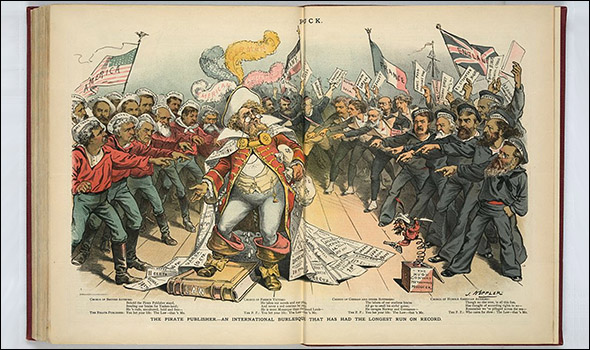

As this image from a February 1886 issue of the magazine Puck illustrates,3 the focus of this legal-illegal divide is on the pirate publisher: one who takes something and publishes it without the permission of (and — almost inevitably — without compensating) the creator. Because early copyright law was all country by country, it was common for — say — a Dutch publisher to grab a work published in England and republish it in The Netherlands on the grounds that the English author wasn’t protected by Dutch copyright law.

It was largely because of that pirate publisher that, in 1886, we saw the adoption of the Berne Convention — the key international treaty recognizing copyrights across national boundaries.4

And because of that international treaty, initially adopted by just 10 countries5 and now the law in more than 170 countries around the world including the United States,6 it really does matter for copyright purposes if the item was legally published or not.

Copyright would apply, all right — but not to the pirated publication.

Let’s consider a specific example.

Best-Selling Novel, written by author John Doe, was published in the United States in 1926. Under most circumstances, copyright would have expired on that book as of 1 January 2022.

But, it turns out, John Doe never authorized that publication. He had asked his nephew, Richard Roe, to read it and give his opinion. Richard recognized the commercial value in the manuscript and scurried over to Pirate Publisher who published the book in 1926. John himself was traveling around the world and didn’t know the book had been published until he returned to the United States in 1930, when he went to court to stop the Pirate Publisher and instead allowed the first authorized publication by Upstanding Publisher. That edition was published in 1931.

Under these facts, the 1926 publication was unlawful. It wasn’t authorized by the creator of the work. So neither Richard nor the Pirate Publisher had copyright on the work, and the copyright clock wasn’t started by that publication.

The time wouldn’t have started running until the first legally authorized publication — and that was five years later, in 1931. So copyright on the book won’t expire until five years later, as of 1 January 2027.

And that’s why I keep stressing legal or lawful publication.

For the pirates out there, no copyright for you!

And for those of us who want to use the work, the key copyright date is the date of first lawful publication.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “About that legal limit…,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 18 Feb 2022).

SOURCES

- Judy G. Russell, “The risks of orphan status,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 17 Feb 2022 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 18 Feb 2022) (“everything lawfully published in the United States before 1927 is now in the public domain because copyright has expired”). ↩

- Matthew Shaffer, comment to “The risks of orphan status,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 17 Feb 2022. ↩

- Joseph Ferdinand Keppler, “The Pirate Publisher,” in Puck, v. 18, no. 468 (24 Feb 1886); Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division (http://www.loc.gov/pictures/ : accessed 18 Feb 2022). ↩

- See generally “International Copyright: History Of The Berne Convention,” Law Library – American Law and Legal Information (https://law.jrank.org/ : accessed 18 Feb 2022). ↩

- See Wikipedia (https://www.wikipedia.com), “Berne Convention,” rev. 8 Jan 2022. ↩

- See “Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, Status on January 28, 2022,” World Intellectual Property Office (https://www.wipo.int/ : accessed 18 Feb 2022). ↩

I was just pondering when a work I have, which was copyrighted in 1930, would be out of copyright. Thanks for a timely post!

Remember that there were some formalities that were required back then, so this answer assumes they were all complied with.

This begs the next question — what does “published” mean in the legal sense? It is my understanding that for something to have been “published”, it must have been theoretically possible for an ordinary member of the public to have legally acquired a copy of the thing back at that time.

It doesn’t “beg” the question at all — it simply doesn’t address it. This does: https://www.copyright.gov/comp3/chap1900/ch1900-publication.pdf