Freedom tiptoes into Pennsylvania

The Legal Genealogist spent essentially every day of elementary school, junior high school, and high school in the public schools of the north.

We studied the Civil War in different ways in different years.

And the one sentence I never heard, not once, in all those years, was: “There was slavery in the north.”

It wasn’t until I was well-advanced as a genealogist that I began to come across the evidence:

• New York held more than 21,000 people in bondage as of the 1790 census — the most in the north.1

• New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey all reported enslaved residents on the United States census of 1840.2

• There are surviving U.S. census slave schedules for 13 of New Jersey’s then-20 counties for 1850 that you can find on Ancestry or FamilySearch.3

• There were even 18 people still listed as “apprentices for life” on the New Jersey census enumeration of 1860 — true freedom didn’t arrive for them until the passage of the 13th amendment in 1865.4

Vermont was the first northern state to abolish slavery, as the Republic of Vermont, in 1777, but — as so often was the case — there was a disconnect between the law and the reality.5

And it wasn’t until March of 1780 that the next step was taken: Pennsylvania — founded by William Penn as a haven in the New World for the persecuted Quakers — took its first tiptoe step towards freedom within its own borders.

And that first tiptoe step did not free those held enslaved in Pennsylvania.

Act 881 of the Laws of 1780 declared that “all persons, as well negroes and mulattoes as others who shall be born within this state, from and after the passing of this act, shall not be deemed and considered as servants for life or slaves; and that all servitude for life or slavery of children in consequence of the slavery of their mothers, in the case of all children born within this state from and after the passing of this act as aforesaid, shall be and hereby is utterly taken away, extinguished and forever abolished.”6

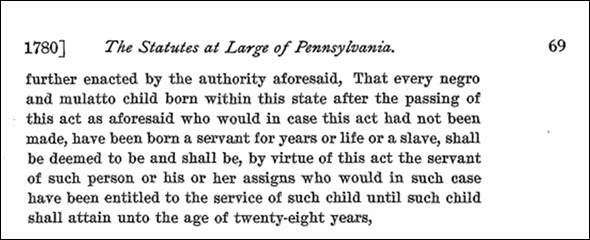

But, the law continued: “every negro and mulatto child born within this state after the passing of this act as aforesaid who would in case this act had not been made, have been born a servant for years orlife or a slave, shall be deemed to be and shall be, by virtue of this act the servant of such person or his or her assigns who would in such case have been entitled to the service of such child until such child shall attain unto the age of twenty-eight years…”7

And, it said, those who then claimed ownership of any person could keep that person enslaved by registering ownership with the county clerk.8

Which is, of course, the silver lining to this law’s cloud for genealogists: it created records. First, there were the registrations of the ownership of persons then held enslaved. Later, there were registrations of the births of the children who owed service to the enslavers of their mothers. Similar records can be found in most of the northern states that eventually adopted a system of gradual emancipation (including New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, among others).

The Pennsylvania law was the first such. At the time, it was considered revolutionary. “In hindsight, the Pennsylvania law was actually the most restrictive of the five gradual abolition laws passed in northern states. With its provisions for 28 years in bondage, the law gave a two generation grace period for slavery to die out. Total abolition did not happen in Pennsylvania until 1847.”9

A first tiptoe in Pennsylvania towards freedom.

And away from the reality we were never taught, of slavery in the north.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “In March of 1780,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 24 Mar 2022).

SOURCES

- Pauline Toole, “The slow end of slavery in New York reflected in Brooklyn’s Old Town records,” NYC Archives blog, posted 26 Feb 2021 (https://www.archives.nyc/blog/ : accessed 24 Mar 2022) (New York was “the Northern state with the largest number of enslaved people”). ↩

- Kathleen Logothetis Thompson, “When Did Slavery Really End in the North?,” Civil Discourse blog, posted 9 Jan 2017 (http://civildiscourse-historyblog.com/ : accessed 24 Mar 2022). ↩

- Check it out: you can find them online, free, here on FamilySearch. ↩

- See James J. Gigantino, II, The Ragged Road to Abolition: Slavery and Freedom in New Jersey, 1775-1865 (Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014). ↩

- See Harvey Amani Whitfield, The Problem of Slavery in Early Vermont, 1777-1810 (Barre, Vt.: Vermont Historical Society, 2014). ↩

- §1, Act 881, Pa. Stat. L. 10: 67, 68; Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau (http://www.palrb.us/default.php : accessed 24 Mar 2022). ↩

- Ibid., §2, at 69. ↩

- Ibid., §3. ↩

- Thompson, “When Did Slavery Really End in the North?” ↩

Thank you for illuminating the legal facts associated with slavery in the North.

And in Canada: I remember being totally shocked when I read the list of provisions provided to individual Loyalist families coming to Canada… and first seeing slaves on several family lists. They’re not labelled as slaves, nor as negroes – but they have no surname, and each receive a smaller allotment of food than the rest of the [white] families. I was so shocked I lost my breath. How did we manage to hide these important details – when they were literally right there in the historical documents we were searching for our UEL ancestors-?!!

Canada did become quite the safe haven, however — which is more than can be said for many northern states.

Interesting — I grew up attending public K-12 schools in the North (in the 1970s) and then was a history major in college (in the 1980s), and at both levels we did hear about slavery in the North. Might depend a bit on the specific schools?

What we didn’t get was any contextualizing of human slavery. It wasn’t until much later that I understood that enslavement had been normal across human civilizations on all continents for thousands of years; I still remember the day I first understood that. It pretty well threw me to be honest and has altered my sense of the great historic civilizations to this day.

I suspect it had more to do with time — I am older than you.