The value of a document’s every word

Reader J. Paul Hawthorne came across some language in a late 19th century will, and wondered if he was reading it right.

On the 29th of April 1879, Elisha Myers of Butler County, Alabama, executed a will leaving everything to his wife Ann, but on her death anything remaining was to be divided among his four children: sons James, William and Pryer, and daughter Ann (Myers) Albertson. Myers then died on 14 July 1886 and the will was admitted to probate on 7 December 1891.1

“To me, it looks like the husband gets ‘power’ even after the wife dies,” Paul wrote. “Basically, she gets everything after he dies, real and personal. Great… Perfect. But, when she dies (according to his wishes), everything gets split up between their children.”

So, he wanted to know, “What if the wife decides to make her own Will? What if she decides to give what’s left to a charity or a sibling, and NOT her children? Does her Will overrule his? Or, do his wishes stand?”

Great question — because this is at a time when married women were gaining more property rights, among them the right to make their own wills.2 Alabama had been one of the earliest states to pass a Married Woman’s Property Act, in 1848,3 and a historical review of wills of propertied Alabamians suggests that wives received outright ownership of property from their husbands as often as half the time in the years leading up to the Civil War.4

And it’s a great question — because we don’t really need to look at the law for the answer.

Because the answer is right in the will.

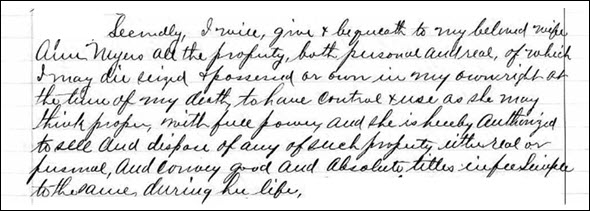

You see, Elisha Myers didn’t simply leave everything to his wife Ann. He left her everything “to have control & use as she may think proper, with full power, and she is hereby authorized to sell and dispose of any of such property either real or personal, and convey good and absolute titles in fee Simple to the same, during her life.”5

Read that again.

Taking out some of the words to make it clearer: he left her everything “to have control & use as she may think proper, … during her life.”

It’s those words — “control & use … during her life” — that make all the difference in the world.

This is in reality a life estate, by definition, “An estate whose duration is limited to the life of the party holding it, or of some other person; a freehold estate, not of inheritance.”6 This isn’t absolute ownership. He’s giving her the right to use and control everything, even up to and including selling off the land if she chose to — but only during her lifetime.

It’s a very liberal life estate to be sure, but it’s still a life estate. Anything left over at the time of her death then goes to the kids.

So yes, indeed, Paul is right: the husband here is exercising power beyond the grave to control the disposition of property after his wife’s death.

But because of those few words in the document, it’s his property that he’s controlling, not hers. He never gave her full ownership; he only gave her a life estate.

It’s a great example of the value of a document’s every word — and why we as genealogists need to be sure we’re reading and recording and properly understanding every one of those words.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “Power beyond the grave,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 31 July 2023).

SOURCES

- Butler County, Alabama, Will Book 3: 182-184 (1891); digital images, “Alabama, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1753-1999,” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 31 July 2023). ↩

- See generally “State Law Resources > Married Women’s Property Laws,” American Women: Resources from the Law Library, Research Guides, Law Library of Congress (https://guides.loc.gov/american-women-law/state-laws : accessed 31 July 2023). ↩

- Act No. 23, An Act Securing to married women their separate estates, and for other purposes (1 March 1848), in Acts… of the State of Alabama 1847-1848 (Montgomery: McCormick & Walshe Printers, 1848), 79 et seq.; digital images, Google Books (https://books.google.com/ : accessed 31 July 2023). ↩

- Ann Williams Boucher, “The Plantation Mistress: A Perspective on Antebellum Alabama,” Chapter 2 in Mary Martha Thomas, ed., Stepping Out of the Shadows: Alabama Women, 1819-1990 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995), 41. ↩

- Will of Elisha Myers, Butler Co., Ala., Will Book 3: 183. ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 720, “life estate.” ↩

Hello Judy, welcome back, glad you’ve survived your move.

In South Africa’s Roman-Dutch law system, we call this a usufruct, often given as a life interest or for estate planning purposes, or to control the future ownership of farm lands.

From the Latin usus and fructus – the use and the fruits.

Sometimes the clarity of Roman law principles and terminology helps the analytical understanding …..

Warm regards

Adv. Dave Mitchell

Cape Town, South Africa

Hi, Dave, and thanks. Yes indeed, despite the overall differences in the two legal systems, there’s a lot in common between the life estate (common law) and the usufruct (civil law). About the only real difference I know of is that the civil law can split the life estate from the usufruct, and you won’t see that in common law life estates. Here, this widow was given a very liberal right to use and benefit — she could even sell the real estate and use the money for whatever she wanted.!

It’s good to have you back.

ditto!

I suppose there is something of a possible side benefit. Should his widow die without leaving a will, the inheritance is already mapped out in his.

Thank you for clarifying and putting the answer in down-to-earth words. You are simply the best! Hope to see you again at another conference or institute… although, it looks like they’re staying virtual in 2024.

Delving into the fascinating intersection of genealogy and legal matters, this article highlights the intriguing ways individuals continue to wield influence even after passing, sparking thought-provoking reflections on legacy and inheritance.