And furthermore…

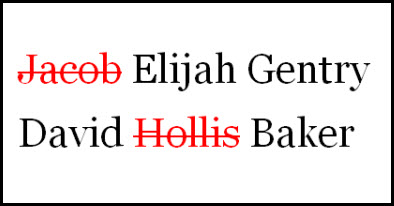

So yesterday, in the course of reviewing the DNA evidence that disproves persistent family lore of Native American ancestry, The Legal Genealogist whined about the fact that so many cousins want to turn third great grandfather Elijah Gentry into Jacob Elijah Gentry.

Why Jacob?

Why Jacob?

I have no idea.

But there were, as of yesterday, 201 family trees on Ancestry.com — 167 public and 34 private trees — that listed Elijah Gentry of Mississippi as Jacob Elijah Gentry.

Even more infuriating is that Ancestry itself has “compiled” those trees in its new “Life Story” feature to seemingly confirm that he really was Jacob Elijah Gentry.

They’re all wrong. Wrong about his name, wrong about his wife’s Native American ancestry — wrong, wrong, wrong.1

And, just for the record, my fourth great grandfather — Revolutionary War soldier David Baker of Culpeper County, Virginia, and Burke (later Yancey) County, North Carolina — was just David Baker.

Not David Hollis Baker, as some 580 family trees on Ancestry.com — 454 public and 126 private trees — all seem to report, and as that blasted “Life Story” feature appears to confirm.

He was David Baker in his Revolutionary War service records.2 David Baker in his multiple land entries in Burke County, North Carolina, starting in 1778.3 David Baker in the United States census as early as 1790.4 David Baker when he took the oath of office as a Justice of the Peace in Burke County, North Carolina, in 1797.5 David Baker in the tax list of 1803.6 David Baker in his Revolutionary War pension application.7 David Baker when he signed his last will and testament in 1838.8

Always David Baker.

Never David Hollis Baker.

Except… sigh… in 580 family trees on Ancestry.com, which is compiling all those wrong trees into a wrong “Life Story.”

Folks… stop it.

Stop all this middling along.

The reality is that middle names were rare in America before the 19th century.

As Robert W. Baird reports in “The Use of Middle Names”:

Prior to 1660, the Virginia Settlers Research Project found “only 5 persons out of over 33,000 had genuine middle names.” Not one person born by 1715 in St Peter’s parish of New Kent County sported a middle name. Surry County’s records, which are unusually complete for the latter part of the 17th century, record only one person who used a middle name. Other studies of public records confirm that seventeenth-century parents gave their children more than one name so rarely that the practice was essentially nonexistent.

Middle names began to find favor among wealthy extended families in the late 1700s. Aristocratic families increasingly began giving their children two names, so that by the time of the Revolution a quite small but detectable proportion of southerners carried middle names, mainly those from upper class families. A study of the births and baptisms recorded in the register of Virginia’s Albemarle Parish shows that about 3% of children born between 1750 and 1775 were given middle names.

… The practice did not really catch on with the middle class until after the turn of the century, and became increasingly common within a generation or two. Although only a small percentage of children born around 1800 were given a middle name, it had become nearly customary by the time of the Civil War. By 1900 nearly every child born had a middle name.9

That conclusion — that middle names for ordinary families didn’t catch on until later — is supported by Rhonda R. McClure in “A Look at Middle Names”:

Few Americans were giving their children middle names … until the German immigrants introduced this naming custom to America.

… (I)t was not until the early 19th century that the custom caught on with others. By the 1840s, it had grown into a popular practice. According to a study of college records, in 1840 about 92 percent of the students at Princeton had middle names. This custom would continue to grow and by World War I it was assumed that everyone in America had a middle name.10

And you’ll find many other references to middle names as infrequent before the 1800s if you’ll just stop and look.11

So do us all a favor and face the facts.

Adding a middle name to an ancestor where the records don’t even hint at a middle name does us all a disservice.

So stop it.

Stop middling along.

SOURCES

- See Judy G. Russell, “No, no NA,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 23 Aug 2015 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 24 Aug 2015). ↩

- Compiled Military Service Record, David Baker, Cpl., 3rd Virginia Regiment, Revolutionary War; Compiled Service Records of Soldiers who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War, microfilm publication M881, 1096 rolls (Washington, D.C. : National Archives Trust Board, 1976); digital images, Fold3.com (http://www.fold3.com/ : accessed 23 Aug 2015). ↩

- See e.g. Burke County, North Carolina, Land Entry No. 227, James Baker, David Baker, Charles Baker and John Baker (1778); North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh. Also, ibid., Land Entry No. 3239, David Baker (27 Jan 1797). ↩

- 1790 U.S. census, Burke County, NC, p. 91 (penned), col. 1, line 1, David Baker; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 23 Aug 2015); citing National Archive microfilm publication M637, roll 7. ↩

- Burke County, North Carolina, Court of Common Pleas Minutes, 23 Jan 1797; North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh. ↩

- Burke County, North Carolina, Tax Lists 1803-1804; North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh. ↩

- Affidavit of Soldier, 26 September 1832; Dorothy Baker, widow’s pension application no. W.1802, for service of David Baker (Corp., Capt. Thornton’s Co., 3rd Va. Reg.); Revolutionary War Pensions and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, microfilm publication M804, 2670 rolls (Washington, D.C. : National Archives and Records Service, 1974); digital images, Fold3.com (http://www.Fold3.com : accessed 28 Apr 2012), David Baker file, pp. 3-6. ↩

- Yancey County, North Carolina, Record of Wills 1: 30, will of David Baker, 26 Jan 1838; North Carolina State Archives microfilm C.107.80001. ↩

- Robert W. Baird, “The Use of Middle Names,” Bob’s Genealogy Filing Cabinet (http://www.genfiles.com/ : accessed 23 Aug 2015). ↩

- Rhonda R. McClure, “A Look at Middle Names,” Twigs & Trees, posted 18 Apr 2002, Genealogy.com ( : accessed 23 Aug 2015). ↩

- E.g., Oren Frederic Morton, A History of Rockbridge County, Virginia (Staunton, Va. : McClure Co., 1920), 339; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 23 Aug 2015). ↩

And if we DO find a middle name earlier than was customary, we should sit up and take notice. Is there some special significance to this name? Knowing that middle names were, indeed, rare led me to my first Mayflower connection.

Adding a middle name may be an attempt to force a connection that is NOT there as well.

Oh yes… if there WAS a middle name earlier, it will usually provide a clue to a family connection.

Thank you for mentioning the German naming custom of giving children a middle name. The 17th and 18th century German church records illustrate that a first name and a middle name was the norm-a tradition carried down through the generations. To make it a bit more interesting, most of my ancestors preferred to be called by their middle name and, over time, sometimes the first name was forgotten.

Now if I can just figure out whether my gg-grandfather was Anderson Caswell Collins or Andrew Caswell Collins. He is recorded in all records located as A.C. (or in the case of the 1860 census, Ann C.) This has been, of course, a subject of serious debate, argument, and verbal rock throwing among certain members of the family for years. 🙂

Tell me about it — my own grandmother’s middle name has been the source of dispute for years!!

Humm…I thought I had read somewhere that the German first name was “religious” and people went by their middle names. It certainly worked that way for my 1600’s and 1700’s German families, both male and female. I think I am going to spend this end of the year/beginning of next rereading some of my early sources.

That was a common system, but not the only system, Nan. The German call name was, occasionally, the first name.

Hello Suzanne – not sure if you will even get this because you posted 5 years ago but my relative is Andrew Caswell Collins for sure and was wondering if you found anything out.

Kitty – Andrew Caswell is my husband 3rd great grandfather. I too am looking for any information. I am trying to do the research for my father in law. Many thanks.

Your Pettypool cousins in western South Carolina got themselves a ‘middle’ name by breaking Pettypool into ‘Petty’ and ‘Pool’- Seth Petty Pool, Berry Petty Pool, etc. And thereby precipitated two myths, still alive and well today. Myth 1. we are in the Pool(e) family- see the FTDNA Poole project for a current example

2. using other well known genealogy “rule” about names, the assumption has been made that the newly minted Pool boys were sons of women from the Petty family who married into the Pool family, a conviction I still find as I wander the state talking about Pettypools.

Oh ouch… Pettys marrying Pools. Ouch. 🙂

I am very familiar with the Pettypool situation. One of my great-granduncles, Thomas A. Holtzclaw, married Nancy Pettypool. Her maiden name is abbreviated on the tombstone as P’Pool and has been transcribed as P. Pool in numerous transcriptions. Either the dear souls who did the transcribing never looked at the tombstone or didn’t bother to transcribe it correctly.

You and Jim will be closer cousins than you and I are, then (I’m from the NC branch, he’s from the SC branch).

Suzanne Matson: If you have not already done so, would you pass on the linage information you have on Nancy Pettypool to our Pettypool One-Name Study? You can find an email link to the project administrator- Carolyn Hartsough- at our website: http://www.pettypool.com.

Thank you

My father was an exception. Born in 1911, he had only one given name.

There will be LOTS of exceptions, Melba.

Some of the exceptions are exceedingly odd…my grandfather was Campbell Cramer. For some reason some official decided he needed a middle name and gave him the initial “B”. Just an initial, no name. Sigh.

And then there are those who have ONLY initials — no first names at all!

If only this post could be in all the ancestry forums and if their blog person would reference it AND if it could turn into a youtube ancesty video. Won’t stop it, might slow it down.

I’ve been chasing the middle name of Dimmott because my great grandfather was given it in 1804 in PEI. A possible sister has Clark as a middle name and that opened up the Saunders genealogy. All those clues have done is give me a giant headache! ALL of the other middle names in my family have led me down the right highway. Dimmott? Not a clue.

Better to have the clue than not, though!

I think that is called “spitting in the wind.” 🙂

Yeah, well, better to light a candle than curse the darkness!

^^^ Love that! ^^^

Bravo! As you so well note, these things are nearly impossible to kill. I don’t necessarily agree with Robert Baird when he says middle names only became fashionable among the upper class in the late 1700s. There are ample instances of this practice much, much earlier than that, e.g. Henry Skipwith Carter b. 1676 in Lancaster Co., VA (named for his grandfather Sir Henry Skipwith) and Peter James Bailey b. ca 1690 in the same place (evidently named for Deputy Clerk Peter James and his Godfather, and whose will left him a nice legacy). But those are very rare and far between. An instant red flag are names from, say the 1740s and a daughter is called Hannah Elizabeth. No, she was either Hannah OR Elizabeth, but not both. Of course the internet is polluted with sort of thing. One exception to this, though, is the use of Ann as in MaryAnn or SaryAnn or even Sarah Ann. I don’t know that I agree that is was the German immigration that made this a popular fad. Places with absolutely zero German element began using middle names after the Rev. War.

Thanks for addressing this practice of adding a middle name to ancestral records when no middle name existed. I’m seeing it more frequently plus if there is a father and son, these people are adding Sr. and Jr. to the names. Arrrggghhh… I’ve addressed the mistake on my family tree where possible, but with all the copycats out there who don’t do real research and just copy mistakes over and over from each other, it feels like protesting is a lost cause. The new story view concept on ancestry.com is going to cause massive numbers of mistakes to start appearing also. I previewed it and offered my opinion to ancestry.com that the story view was a horrible idea because of inexperienced people not understanding how to use it.

The story view is going to compound things, for sure. When you multiply garbage, it’s still garbage…

To add to the confusion and frustration, we find nicknames in records such as Polly when the person’s given name was Mary. That gets turned into Mary Polly Doe. Or my personal favorite (insert sarcasm and dismay) “I heard that my aunt said her mother’s grandmother said that my g-g-g-grandparent’s name was Jerry Doe” and every single solitary document, including those the ancestor signed, shows that ancestor never ever went by anything other than John Doe.

If it’s oral history, state that. If it’s theory based on circumstantial evidence, state that. If it’s facts found in documents, state that. If it’s 3rd and 4th party hearsay, don’t state it as fact . It only adds to confusion in research and tells tales about our ancestors that ain’t necessarily so.

I wished and it seems like a lot of others wished, but its almost too late. A lot of family history will be assumed by those looking later in life at these mistakes. In earlier years I made terrible mistakes, was just fortunate enough to have some genealogical cousins step forward and show me where I was wrong. Thank you Judy Russell and H. Charles Baker.

I have a similar situation with one of my ancestors, who somewhere along the line was handed the first name of William. He was born Oliver, no middle name, he is listed as Oliver in every document or reference I’ve seen for him, both public and personal, and yet online genealogy after genealogy simply passes along his name as William Oliver Stratton. William IS a common name in that line, usually appearing multiple times in each generation. All of Oliver’s sons (born in that period after the Revolution when middle names came into vogue) had middle names, thank goodness, it makes them easier to trace. And oddly enough, as soon as middle names were introduced, it became a common practice in my family for people to use their middle names (as do I). My ancestors love to torture me. One of Oliver’s grandsons was indeed named William Oliver– and was simply called Oliver, no doubt to distinguish him from all the other Williams in the family by that time. Which is another reason adding William where the name does not exist makes no sense. I wish people would just LOOK at the supporting evidence (or lack thereof) before just assuming something is fact. This sort of thing makes me crazy.

Again, I am always wondering how these myths get started in the first place. A recent example is a client who insists his ancestor’s name was Dandridge David Davis. I cannot get him to budge off that, as there is no record of his name other than Dandridge Davis, period. Even his tombstone and obituary (alas, just prior to death certificates). Why is he so adamant on this? Because his aunt Lucille said so, and she was a granddaughter and ought to have known. Reminding him of aunt Lucille’s other many errors makes no dent in his thinking on it. Why did aunt Lucille say this? No idea.

I have some experience with Davis logic 😉 – my maternal ancestors were Davis. This “David Davis” might be a mangled echo of the long abandoned patronymic naming system used by Davis families originating in Wales.

One of my German families married into the Bucks county Welsh Baptists and I am drowning in patronymics.

My grandmother, born in 1900, had no middle name, despite her siblings having middle names. She was the youngest of twelve and she told me that by the time she was born, her parents could no longer think of two names — they had all been used for the older eleven. So “I got only one.”

Believe it or not, I have had a bit of success getting some people to correct this type of mistake on Ancestry. My great grandfather’s own kids didn’t even know his correct first/middle name combination, so that’s why it’s so commonly mistaken. However, when I noticed an important trend – that legal documents he filled out never had a middle name and used what people thought was his middle name as a first name – that’s when we figured out his “real” name. The assumed “correct” first name was really just a nickname. Unfortunately, it makes it wrong on all of the death certificates of his kids since not even they knew!

This is an excellent point. One of my ancestors is Samuel J. Blackwell, died 1864 in St. Louis County. Every single record of him is as Samuel J. Blackwell. But his probate file calls him Johnson Samuel Blackwell. Who knew? I call him Samuel Johnson Blackwell.

Another problem at least in my family tree is the use of nicknames. This was real popular in the midwest and south. So I have Augustus or gus, James is john, johnnie, jim, etc. Its crazy because when you look at newspapers they are going by the nickname not the legal name. I wrote for a newspaper and used a guys name which I was told later with much tch, tch is that was not is name he was so and so. I about had a fit. He told me his name, and that is what I used. So a good rule of thumb when interviewing a relative ask to make sure that they are using their legal name not a nickname.

Adding undocumented middle names is close to the top of my list of genealogical pet peeves. I believe it stems in part from what historians consider the greatest sin against their craft — engaging in ANACHRONISM. (Anachronism is most often used to describe a situation in which something has survived long beyond its time, but in fact means anything out of its time — hence, an assumption that the past was like today is also an anachronism.)

As an example of the lack of middle names among Americans born before 1800, I like to cite the first 17 Presidents of the United States. Among those 17, Washington, John Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Jackson, Van Buren, Tyler, Taylor, Fillmore, Buchanan, Lincoln, and Andrew Johnson had no middle names. John and Abigail Adams gave their four sons middle names, starting with John Quincy (b. 1767), but a consistent run of middle names did not start until U.S. Grant. (Stephen Grover Cleveland, Thomas Woodrow Wilson, and John Calvin Coolidge, by the way, did not use their first names.)

In my own family surnamed English, middle names started, almost abruptly, in 1811. In the Goodloe family, who were prosperous colonial Virginia gentry, they were not generally used until 1800.

My own rule is: Never accept the alleged middle name of a subject of research unless you find at least one CONTEMPORANEOUS (with the life of the individual) document that provides evidence of that name. There may be exceptions, but they should be put through rigorous analytical scrutiny and correlation as called for in the Genealogical Proof Standard.

I agree and am constantly dismayed, surprised (and yet not surprised) at the sheer number of inaccurate names pinned on one of my ancestors on a popular family tree/research website. He has also been listed as being married simultaneously to his own wife in addition to his brother’s wives, maybe because his name is frequently combined with his brother’s names. One of these names actually made it onto a grave marker placed at his grave by a non family member who was/is connected to a local historical members only club. The family found out after the fact.

But I digress. This particular ancestor used only one name in each and every document I have found, with several exceptions. These are contemporary news articles and documents showing he had a nickname or possibly middle name. As your last paragraph states (and I heartily agree) don’t accept the middle name unless you can find documents that support it. Otherwise, my personal notion is that without supporting documentation, oral history should be stated as such.

Absolutely: when it’s oral tradition, say so!!

Oh, and by the way, the documented nickname/middle name I mentioned above isn’t even close to the oral history version.

Oral history is a wonderful, valuable thing to be cherished and can often provide great leads in research. Sometimes actual documents aren’t 100% foolproof accurate. I think the key here is to be accurate in one’s statement of source. Sadly, this is often seen to be the opposite of what is practiced by too many folks.

I think it’s important to strive for accuracy, we owe it to our ancestors and to future researchers/genealogists regardless of their interest levels.

Just my two cents. 🙂

THEN you have those who named their kids after famous people, which includes their whole name. Hugh Wilson Ross is one. He was b around 1800. Always listed as H W, Hugh W, Hugh Wilson Ross.

My grandmother had an aunt who was given 21 names before her maiden name. I guess she could not decide, and they named her all of them. She went by Fern Ross.

My Ross family was quite inventive on names and used a lot of Latin and Classical names.

Plenty of those, for sure. My own Elijah Gentry named one son John Wesley (founder of Methodism) and another Ira Byrd (another Methodist preacher).

Forgive me for having a chuckle regarding your frustration with what appears in the so highly error-riddled trees. Mainly all we can do is keep our own genealogical corners as well documented as we can, and hope that others will copy the good instead of the majority of what’s out there.

Yes, we can hope that… but experience sure suggests otherwise.

Oh, how I wish more people would STOP being so inventive with names! I have a gg-grandfather who was always either Davie, D C or David C Sisk. Now, I’m finding him on Ancestry.com as David Crockett Sisk, David Clarence Sisk, and even – Daniel David Crockett Sisk! Grrrrrrr. I’ve written some of the contributors asking for documentation of his many name changes and so far, no one has answered me. I’m sure it’s another case of “she said that Aunt said that Cousin said” and it gets all gummed up. On the other hand, there was another family nearby in Murray County, GA who had similar names. David’s father has also been given a middle name, and his mother’s names are as varied as the weather! But it’s all listed as fact on Ancestry.com. To further complicate things, MY David Sisk is a Cherokee Indian, living in a community of Cherokees in that census. The other Sisk family is nowhere near the settlement.

Sigh… everybody wants to be related to somebody famous, I guess.

Enjoyed reading all your stories. My paternal lineage is from Scotland and France. I have loads of ancestor, not only with a middle name but multiple middle names. Most of my Scottish ancestors like to pass on the surnames of a favorite relative as middle names for their children. It was so common I accepted some names as correct before actually checking the original records and I found a few of the records had added the persons occupation as a surname. One annoying mistake is for the name of my 2X great grandfather James Hay All the major genealogical sites list him as James “Thomas” Hay. He never had a middle name, but when his birth was recorded in the Parish Register, they did enter Thomas as his first name and then crossed it off and wrote James above it. James was the only name he used for his whole life.

I have recently discovered BMD records for my French ancestors and found many of them were using their middle name as a first name when they came to the states. All the US records only showed my 2X great grandfather, as Alphonse Bailly, when his real first name was Joseph. Another name problem for me is searching for Pierre but after immigrating he becomes Peter or Jose becomes Joseph. researching family history is such fun. 🙂

European naming patterns were different from those in the US. But oh yes… it is fun, isn’t it?

Darn it, this is so true. For over 20 years folks been telling me that my great great grandfather who is Parley Worden, was actually Amos Parley Worden, purely because of the name Parley. My great great grandpa is just simply Parley, not Amos and further more, the other man named Amos Parley Worden is not his father, he would of been about 12 yrs old to have my Parley. Pay attention to the ages of folks, 1 plus 1 does equal 2. We need some “common sense genealogy” folks (good title for an article Judy!

Oh yeah… Some of that uncommon common sense would sure help!!

My Father had one middle name on his birth certificate and two middle names on his baptismal certificate. All his life including his marriage certificate he used both middle initials. I have two middle names on my actual birth certificate. Early computers could not accept two middle names so my Driver’s License, SS card, and school records all only use one middle name. Ancestry has my birth certificate index record with only one middle name.

Sometimes our name gets changed by society and the paper trail we leave.

Double given names are largely a post Civil War pattern in America.

The middle names seen earlier are more than likely maiden names and ancestral surnames used to name children or unmarked patronymics.

You see the first in John Quincy Adams (Quincy was Abigail Adams mother’s maiden name) or James Knox Polk (James Knox was the maternal grandfather).

Unmarked patronymics are names like John William Jones where the father was named William and his name was added in the middle position. This looks like a middle name but it is not the same as our modern middle name practice. It is most common in areas of Dutch and northern German settlement but it is found in English colonies as a rare practice.

Germans and Russians often use a saint’s name as a second given name. Again this is not the same practice as our modern double given name.

Jean Baptiste is common in French settled areas and is a single given name from St John the Baptist. It is not a middle name.

If you find a middle name in a pre-Civil War Mac or O’ family it is usually a Gaelic descriptive byname. Christian names were not normally used as middle names in Irish and Scottish Gaelic- speaking families.

The further back in time you take your research the more important these name patterns become.

And wouldn’t it be terrific to have source citations for all this wonderful information, hmmmmmm? 🙂