The end of slavery, the beginning of records

Thirty-two words.

That’s all.

Oh, the whole thing is 43 words if you add the second section that gave Congress the power to enforce the first section.

But it was those first 32 words that meant so much.

And they changed the country, forever, for the better.

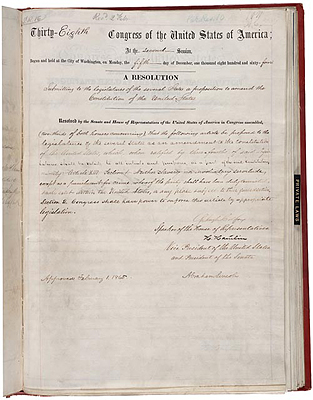

One hundred and fifty years ago yesterday, the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution was finally ratified. In its entirety, both sections included, it reads:

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.1

It had been a long time coming.

Slavery arrived in what became the United States when a ship called the White Lion arrived in Virginia in August, 1619.2 It took a war and an amendment to the Constitution to bring it to a close.

Slavery arrived in what became the United States when a ship called the White Lion arrived in Virginia in August, 1619.2 It took a war and an amendment to the Constitution to bring it to a close.

Even The Legal Genealogist wasn’t aware of the entire history of the amendment. How it was introduced in the Senate on February 8th, 1864,3 and passed there on the eighth of April 1864.4

How it was initially defeated in the House of Representatives on the 15th of June that year.5

How President Lincoln refused to accept no for an answer: “At that point, Lincoln took an active role to ensure passage through congress. He insisted that passage of the 13th amendment be added to the Republican Party platform for the upcoming Presidential elections.”6

How, 149 years ago yesterday, he made a plea to the Congress in his fourth annual message:

At the last session of Congress a proposed amendment of the Constitution, abolishing slavery throughout the United States, passed the Senate, but failed for lack of the requisite two-thirds vote in the House of Representatives. Although the present is the same Congress, and nearly the same members, and without questioning the wisdom or patriotism of those who stood in opposition, I venture to recommend the reconsideration and passage of the measure at the present session.7

How the House took it up again in the early days of 1865,8 And how it finally passed the House on January 31st, 1865.9

How Illinois was the first of the states to ratify the proposed amendment, voting on the first of February, followed the next day by Rhode Island, and the day after that by Michigan, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania and West Virginia.10 How the number of states kept growing through the early months … and then stalled.

Ratification by 27 of the 36 states was required. By the fall of 1865, 23 had given their assent. But it needed the support of states that had been in rebellion to become law. South Carolina voted in November. Alabama on December 2. North Carolina on December 4. And, finally, on the 6th of December — 150 years ago yesterday — Georgia put the amendment over the top.11

And those critical 32 words became the law of the land.

From a genealogical standpoint, this is a high watermark day. Individuals who had been little more than tick marks on a slave census, or first names in a property list, gained legal recognition as full legal persons — and records began to be created in their own names, rather than in the names of slaveholders.

Among the very first, and very best, records for a genealogist looking at these newly freed Americans are the records of the Freedmen’s Bureau:

The U.S. Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, popularly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, was established in 1865 by Congress to help former black slaves and poor whites in the South in the aftermath of the U.S. Civil War (1861-65). Some 4 million slaves gained their freedom as a result of the Union victory in the war, which left many communities in ruins and destroyed the South’s plantation-based economy. The Freedmen’s Bureau provided food, housing and medical aid, established schools and offered legal assistance. It also attempted to settle former slaves on Confederate lands confiscated or abandoned during the war. However, the bureau was prevented from fully carrying out its programs due to a shortage of funds and personnel, along with the politics of race and Reconstruction. In 1872, Congress, in part under pressure from white Southerners, shut the bureau.12

Vast numbers of newly freed Americans — and of equally vast numbers of whites with whom they came into contact, from former owners to employees of the Bureau itself — were recorded in the documents of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

And those records survive.

And, with a little help from our friends, we can all use them and access them much more easily down the road than we can in the hundreds and hundreds of rolls of microfilm and unindexed digital versions where they reside today.

Because there’s a whole indexing project going on that we can join and benefit from.

Head on over to The Freedmen’s Bureau Project — just click on that link, and be prepared to be drawn in to one of the most fascinating sets of records you will ever work with.

It’s a cooperative venture between FamilySearch International and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society (AAHGS), and the California African American Museum. And to make these amazing records really searchable online, it needs all of us to pitch in with whatever time we can give — even a few minutes.

It’s really easy to index: “No specific time commitment is required, and anyone may participate. Volunteers simply log on, pull up as many scanned documents as they like, and enter the names and dates into the fields provided.”13

One hundred and fifty years of freedom.

One amazing set of records documenting an historical time of change and growth.

Just waiting for us to help out … and make everyone’s history accessible.

SOURCES

Image: Thirteenth Amendment, OurDocuments.gov.

- United States Constitution, 13th amendment, ratified 6 December 1865, 13 Stat. 774-775 (18 Dec 1865). ↩

- See “Virginia’s First Africans,” Encyclopedia Virginia (http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/ : accessed 6 Dec 2015). ↩

- Congressional Globe, 8 February 1864, 38th Congress, 1st Session, at 521; digital images, “A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774-1875,” Library of Congress, American Memory (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html : accessed 6 Dec 2015). ↩

- Ibid., 8 April 1864, at 1490. ↩

- Ibid., 15 June 1864, at 2995. ↩

- “13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Abolition of Slavery (1865),” Our Documents (http://www.ourdocuments.gov/ : accessed 6 Dec 2015). ↩

- Congressional Globe, 6 December 1864, 38th Congress, 2nd Session, at 3; digital images, “A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774-1875,” Library of Congress, American Memory (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html : accessed 6 Dec 2015). ↩

- See e.g., 6 January 1865, ibid. at 138. ↩

- Ibid., 31 January 1865, at 531. ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Thirteenth_Amendment_to_the_United_States_Constitution,” rev. 16 Nov 2015. ↩

- See ibid. ↩

- “Freedmen’s Bureau,” History.com (http://www.history.com/ : accessed 6 Dec 2015). ↩

- “The Project,” The Freedmen’s Bureau Project (http://www.discoverfreedmen.org/ : accessed 6 Dec 2015). ↩