And the question of the children

In the middle of the 18th century, a young man from Germany named Jacob Snyder (probably Schneider originally) came to America to make his fortune. Family researchers said he came over as an indentured servant, served his seven years, married… and then died at around the age of 27, leaving a widow with three young children.

He didn’t leave a will when he died there in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, and reader Marcia Snyder only had transcriptions of the Orphan’s Court records of his estate showing that his widow Christiana had served as the administratrix.1

He didn’t leave a will when he died there in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, and reader Marcia Snyder only had transcriptions of the Orphan’s Court records of his estate showing that his widow Christiana had served as the administratrix.1

They showed that, by 1760, the widow had accounted to the court for 148 pounds, 18 shillings and six pence in her hands — and the court had awarded half to her and half to the deceased’s surviving siblings: a brother and sister back in Germany and a sister (and her husband) in Pennsylvania.2 The final payment order was in 1765.3

The language used was one moiety to the widow and one moiety to the brother and sisters, and we all know what a moiety is, right? It’s simply an equal share — in this case, one half.4

Marcia couldn’t understand why a probate court in colonial Pennsylvania could have done such a thing: how could that court have taken half of this estate away from this widow with her three young children?

The answer of course lies in the law. And the law raises a fundamental question about this family that Marcia and other Snyder researchers are going to have to address.

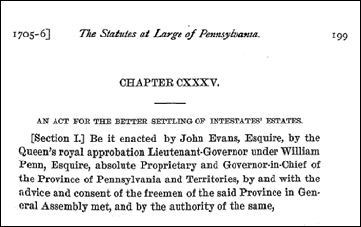

Pennsylvania law on intestate estates — estates where the deceased left no will5 — for this time period begins with the act of 12 January 1705-06, a statute for the “Better settling of intestates’ estates.” That law clearly and unequivocally said that where the deceased left a widow and children, the widow would receive one-third after the debts of the estate were paid, and the children or their legal representatives would divide the other two-thirds equally among themselves.6

And then the statute went on to the critical language for Marcia and her fellow Snyder researchers:

And in case there be no children nor any legal representatives of them, then one moiety of the said estate to be allotted to the wife of the intestate, and the residue of the said estate to be distributed equally to every of the next kindred of the estate who are in equal degree…7

The law was amended twice after 1705: once in 1748-498 and once in 1764.9 Neither of those amendments changed the provision at issue here.

You see the issue right away, don’t you?

Yes, Jacob Snyder left a widow.

But Jacob Snyder — at least according to this court — didn’t leave any children. The division of the estate ordered by the court here could only have been ordered “in case there be no children.”

No matter what’s been passed down through family researchers, there is now specific evidence that the children of the widow were her children — but not his.

This is why we look at the law in the time and the place.

Because sometimes the law itself gives us clues to family structure we can’t get in any other way.

And here it’s telling us to look again at the relationships in this family. Because, according to the law, the Widow Snyder’s children weren’t Snyders at all.

Back to the drawing board for this family’s research…

SOURCES

- The feminine version of administrator. See Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 40, “administratrix.” ↩

- Lancaster County, Pa., Miscellaneous Book 1760-1763, p. 7; Orphans Court, 2 Sep 1760; transcription provided by Lancaster County Archives. ↩

- Lancaster County, Pa., Miscellaneous Book 1763-1767, p. 151; Orphans Court, 10 May 1765; transcription provided by Lancaster County Archives. ↩

- See Black, A Dictionary of Law, 784, “moiety.” See also Judy G. Russell, “Moiety,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 2 Jan 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 19 Jan 2016). ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 640, “intestate.” ↩

- “Better settling of intestates’ estates,” Act of 12 Jan 1705-06, 2 St.L. 199, 201, Ch. 135, in The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania from 1682 to 1809, 18 vols. (Harrisburg : State Printer, 1896-1915), 1: 199 et seq.; digital images, Pennsylvania Session Laws, Pennsylvania Legislative Research Bureau (http://www.palrb.us/default.php : accessed 19 Jan 2016). ↩

- Ibid., at 201-202. ↩

- “Amending the laws relating to the partition and distribution of intestates’ estates,” Act of 24 Feb 1748-49, 5 St.L. 62, Ch. 374. ↩

- “Supplement to the act entitled ‘An act for the better settling intestates’ estates’ and for repealing one other act entitled ‘An act for amending the laws relating to the partition and distribution of intestates’ estates,’” Act of 23 March 1764, 6 St.L. 339, Ch. 512. ↩

Oh, such a good point. And a companion piece to researchers’ assuming that a widow was mother of any number of a decedent’s children.

Your tip for today can also be so complicated a hundred years later, when a woman’s children may be listed in US and other Census enumerations with the surname of the head of household, whether they’d been formally adopted or not. I just finished untangling an example of this problem, comparing elements that just did not add up.

Paying attention to the pesky details is so important!