Two not-so-dissimilar men

Today, the 19th of January, marks the anniversaries of the births of two remarkable American men.

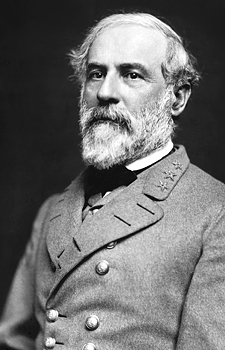

On this day in 1807, in Stratford Hall, Virginia, a son was born to the aristocratic Lee family. The child was named Robert Edward Lee.1

And on this day in 1809, a son was born to a family in Boston, Massachusetts. This child was named Edgar Allan Poe.2

Now little more needs be said about either of these men or their significance in America. Lee went on to become the commanding general of the rebel forces during the Civil War;3 Poe became one of America’s most renowned writers.4

But — c’mon now — this is The Legal Genealogist here. So you have to have a clue as to why I might be interested in such a disparate pair, right?

It’s because each of them was a central figure in a really interesting federal court case.

Poe’s is the more routine of the two — but even though it’s a fairly common type of case, it has its twists.

Poe’s is the more routine of the two — but even though it’s a fairly common type of case, it has its twists.

Poe was terrible at managing money. He drank, he gambled, he ran up debts. In 1842, while living in Philadelphia, his debts got the better of him and he filed for bankruptcy in the federal court in Philadelphia.5

On the petition to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, Poe described his profession as “late editor”6 — he had worked as an editor at Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine and Graham’s Magazine7 — and said he was unable to meet his debts.8

He filed a complete list of everything he owed as Schedule A, including such things as $50 to each of two doctors for medical care, and $5 to a woman named Ann Hughes for rent.

He was, he said, “possessed of no Property, real, personal or mixed, beyond his wearing apparel, and a few printed sheets, of no use to any one else, and of no value to anyone.”9

His estimation of the value of those few printed sheets was a little off…

Lee’s is by far the more complex case. In the years leading up to the Civil War, as the result of his marriage to Mary Custis, great granddaughter of Martha Washington, Lee had come to live in a mansion overlooking the Potomac River in Arlington, Virginia, that later came to be known as the Custis-Lee mansion.10

Lee’s is by far the more complex case. In the years leading up to the Civil War, as the result of his marriage to Mary Custis, great granddaughter of Martha Washington, Lee had come to live in a mansion overlooking the Potomac River in Arlington, Virginia, that later came to be known as the Custis-Lee mansion.10

The mansion was built by Mary Lee’s father, George Washington Parke Custis, and it passed to Mary on her father’s death in 1857.11

The Lees did not enjoy the ownership for long.

Robert, of course, left for Richmond when Virginia seceded from the Union. And in May of 1861, knowing that war would soon engulf their home, Mary Lee left the mansion to join Robert.12

And long before the war had ended, the United States government had taken legal action to strip them of their ownership.

In early 1864, the United States filed an action in the federal court in Alexandria, Virginia, to confiscate all of Robert E. Lee’s ownership interest in the land, the house and its contents.13

Before the year was out, all of Robert’s rights had been seized, the lands sold at auction — the single bidder was the U.S. government, since the property had already been used for the early stages of what is now Arlington National Cemetery for some time by then14 — and even substantial amounts of personal property sold at auction as well: chairs, book cases, bedsteads, wardrobes, fancy candlesticks, a glass case clock, and even “1 large Painting of Washington & his officers on the Battlefield.”15

Mary’s rights were taken because she didn’t appear in person to pay a tax levied on those in rebellion. That condition of personal payment was ultimately held invalid by the U.S. Supreme Court in a 5-to-4 decision in 1882, years after both Lees had passed on. The Lees’ son, George Washington Custis Lee, then sold his rights to the property to the U.S. Government for $150,000.16

Two very different men, two very different cases, brought together by two very similar facts: a day of birth… and a date with a federal court.

SOURCES

Images: Julian Vannerson, Portrait of Gen. Robert E. Lee, officer of the Confederate Army, March 1864, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division. W.S. Hartshorn, daguerrotype of Edgar Allan Poe, 1848, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

- Well… or thereabouts. The date is generally accepted for Lee, but isn’t beyond dispute. See Colin Woodward, “When Was Robert E. Lee Born?,” Stratford Hall (http://www.stratfordhall.org/ : accessed 18 Jan 2017). ↩

- “Who Was Edgar Allan Poe: Poe’s Biography,” Poe Museum (https://www.poemuseum.org/ : accessed 18 Jan 2017). ↩

- “Robert E. Lee,” Civil War Trust (http://www.civilwar.org/ : accessed 18 Jan 2017. ↩

- “Edgar Allan Poe, 1809-1849, Boston, MA,” poets.org (https://www.poets.org/ : accessed 18 Jan 2017). ↩

- In re Edgar A. Poe, a Bankrupt, No. 1304 (1842), U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania; Bankruptcy Act of 1841 Case Files, 1842 – 1843; Records of District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21; National Archives, Philadelphia. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “Edgar Allan Poe, 1809-1849, Boston, MA,” poets.org (https://www.poets.org/ : accessed 18 Jan 2017). ↩

- In re Poe, No. 1304 (E.D.Pa. 1842). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Robert M. Poole, “How Arlington National Cemetery Came to Be,” Smithsonian Magazine, November 2009 (http://www.smithsonianmag.com/ : accessed 18 Jan 2017). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid ↩

- United States v. All the Rights, Titles, of Robert E. Lee (Robert E. Lee Confiscation Case), No. 85, 1864, United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia; Confiscation Case Files, 1863-1865; Records of District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21; National Archives, Philadelphia. ↩

- See Poole, “How Arlington National Cemetery Came to Be.” ↩

- United States v. All the Rights, Titles, of Robert E. Lee (Robert E. Lee Confiscation Case), No. 85 (E.D.Va. 1864). ↩

- Poole, “How Arlington National Cemetery Came to Be.” ↩

History has so many great stories. Even though we have read about this or that particular person, very seldom do we compare their lives by same birthdays. Thanks for this one.

I love your stuff! Where’ve you been all my life??????????

Thanks for the kind words!