Older, younger, say what?

Today is the first full day of the 2017 Salt Lake Institute of Genealogy and a full week of teaching awaits. So nobody will go into withdrawal, however, The Legal Genealogist offers…

The term of the day:

YOUNGER CHILDREN.

Now we all know who the younger children are. I mean, this isn’t exactly rocket science, is it? For there to be younger children, you need (a) more than one kid and (b) one of them to be older.

Easy!

But not exactly.

You see, in English law, the term had a very specific meaning and took into account that there was one child who got a little bit more from his position in the family, no matter where he was in the birth order.

And yes, I’m using the pronoun “he” deliberately… we’re talking here about the oldest son. Remember that in English law, the oldest son got all the marbles when it came to the family land. Under the rule known as primogeniture — the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn son to inherit the family estate, in preference to siblings1 — the oldest boy inherited, even if he wasn’t the oldest child.

So “this phrase, when used in English conveyancing with reference to settlements of land, signifies all such children as are not entitled to the rights of an eldest son. It therefore includes daughters, even those who are older than the eldest son.”2

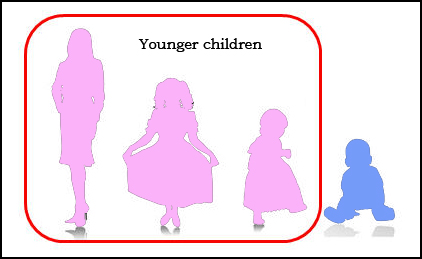

So here, with a family of four, three girls and then the youngest, a boy, you can see… the younger children.

SOURCES

Note: This topic was originally covered in 2013. But hey… it’s still useful!

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Primogeniture,” rev. 17 Jan 2017. ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 1252, “younger children.” ↩

Judy, I have decided that (because of your post of a few days ago) I have an ethical obligation to remind you that when it comes to England’s intestate probate practices — IT DEPENDS. 😉

There is published anecdotal evidence that in at least a few parishes a common practice was for the youngest son to be the sole heir of the intestate estate, including here:

https://books.google.com/books?id=CJhDAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA1076&lpg=PA1076&dq=%22youngest+son+as+heir%22&source=bl&ots=cdmVe6XTBu&sig=G1QIYJHNGyGGHAJlZ0B5PKYm-RM&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj7v6bP5djRAhVJ5mMKHX89DqEQ6AEIJzAD#v=onepage&q=%22youngest%20son%20as%20heir%22&f=false

This practice is called Borough English.

Perhaps a reason for this practice was that older sons had received their portions of the inheritance prior to the father’s death, as they married and formed their own households. This left the youngest son, who had stayed on the home farm to work with the aged father, as the only man who had not already gotten anything.

A more common departure from primogeniture was for all SONS to inherit intestate estates equally. This was especially the case in some parts of Kent. This practice was known as gavelkind.

Been there, done that. See Gavelkind and borough-english. 🙂

So…I looked up the Gavelkind and borough-english blog. Borough-english is what happened in my family back in about 1823, the youngest son, my ancestor, inherited the family farm from his father. We always figured the other sons, quite a bit older, had already left and were on their own somewhere, maybe with help from their father already. Now, I am going to relook the probate/will for mention of maybe why my ancestor got the farm. Thank you Judy and Chad for the tip!