Colonial records online free

It is one of the most compelling pieces of Maryland history.

And one that many researchers have no idea exists… or where to find it.

It’s the Maryland Census of 1776 — and in some counties it goes beyond mere heads of household to list persons both free and enslaved, both male and female, both adult and child.

Indexed at the Maryland State Archives and covering Anne Arundel, Baltimore, Caroline, Dorchester, Frederick, Harford, Prince George’s, Queen Anne, and Talbot Counties, it’s a record explained by the Archives this way:

Beset by skyrocketing debts created by the military demands of the Revolution, Congress took measures to fill the empty coffers of the Continental treasury. On the 26th of December 1775 the members resolved to raise another three million dollars by the further emission of bills of credit.

Congress intended to secure the bills by levying a tax on each colony according to a quota to be determined by population. A copy of the resolution was sent to each of the now united colonies requesting that a census be made of the total population according to race, age, and sex. The results were needed to set the quotas. Not until June 1776 did the Council of Safety in Maryland send copies of the Congressional resolution to the Committees of Observation in each county. These extra-legal committees were authorized to employ persons to take the number of inhabitants and return the lists to them. The Council agreed to pay for the services of the census takers.

The census takers returns varied. Baltimore, Talbot, Dorchester, Queen Anne’s, Caroline, and Anne Arundel counties listed only the heads of households, grouping the number of other individuals in the household by age and sex as is common in the early federal censuses. Other counties like Harford, Prince Georges, and Frederick named each of the individuals, giving their age, sex, and race.1

This is where you can find, for example, that in Prince George’s County, Maryland, in 1776, Thomas Martin was 40 years old, Rozia Martin was 37, Smith Martin was 12, Amelia was 10 and Susanna was one, and the family had two enslaved: Jack, age 27; and Charley, age 17.2 Or that in Harford County, in the Broad Creek Hundred, William Armond was 32 years old, Elizabeth was 28, Thomas was eight, Hannah was six, William was four and Isaac was two.3

Cool stuff, huh?

And you can see it — including, in some cases, reproductions of the actual documents — plus a whole lot more in a reference source that’s readily available, free, online.

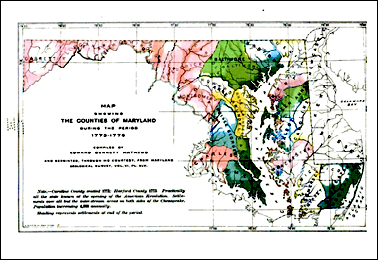

Beginning with the color map of the Counties of Maryland During the Period 1773-1776 that you see here, the work entitled Maryland Records, Colonial, Revolutionary, County and Church, From Original Sources by Gaius Marcus Brumbaugh and continuing in a second volume published some years later is a must-review for researchers from the Old Line State. And the two volumes of this work are digitized, available free, online.

Beginning with the color map of the Counties of Maryland During the Period 1773-1776 that you see here, the work entitled Maryland Records, Colonial, Revolutionary, County and Church, From Original Sources by Gaius Marcus Brumbaugh and continuing in a second volume published some years later is a must-review for researchers from the Old Line State. And the two volumes of this work are digitized, available free, online.

Yep, The Legal Genealogist is still playing in Maryland records and resources in anticipation of Saturday’s Fall Seminar of the Maryland Genealogical Society at the Hilton Garden Inn in White Marsh … and I have to say… these volumes made me drool.

Brumbaugh, a medical doctor who was also a member of the Maryland Historical Society and the National Genealogical Society, published the work back in 1915, focusing on early records of his state. He began his preface to the first volume by noting that he’d included some records — such as the Maryland Census of 1776 — that were often overlooked even by scholars of the time.

The first volume is the one that includes actual reproductions of parts of the census; the second volume a transcription only. Both are taken from the original records available at the Maryland State Archives, which itself offers an index.

But the Brumbaugh volumes offer much more that just that one census:

• Volume I, published in 1915, includes — among other items — marriage licenses from Prince George’s County from 1777-1800, records of All Saints’ Parish in Frederick from 1727-1781, and marriage licenses from St. Mary’s County from 1794-1864.4

• And Volume II, published in 1928, includes — among other items — records of colonial manors, oaths of fidelity from Harford and Prince George’s Counties, some early naturalizations and many early marriage returns.5

And both volumes have an every-name index. Not just showing the last name

Adlum, for example, in volume II, but showing that John Adlum appears on pages 498 and 499 while Margaret Adlum appears on page 498.

Volume I can be found digitized online on Google Books, Hathitrust, Internet Archive, through FamilySearch books, and, for subscribers, on Ancestry. Volume II is on Hathitrust, Internet Archive and, for subscribers, on Ancestry.

Where the actual documents are not reproduced, of course — and much of the information in the two volumes is transcribed or abstracted — the careful researcher will only use the Brumbaugh books as a guide to finding those original source records.

But even as only a finding aid, these volumes are worth their weight in gold to the researcher of early Maryland families.

SOURCES

- “Census Records: Federal Census Schedule Information at the Maryland State Archives,” Guide to Government Records, Maryland State Archives (http://guide.mdsa.net/ : accessed 13 Sep 2017). ↩

- Gaius Marcus Brumbaugh, Maryland Records, Colonial, Revolutionary, County and Church, From Original Sources, vol. I (Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1915), I: 3; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 13 Sep 2017). ↩

- Ibid., vol. II (Lancaster, Pa. : Lancaster Press, 1928), II: 113; digital images, HathiTrust Digital Library (http://www.hathitrust.org/ : accessed 13 Sep 2017). ↩

- Brumbaugh, Maryland Records, Colonial, Revolutionary, County and Church, From Original Sources, vol. I: ix. ↩

- Ibid., vol. II: ix-x. ↩

My persons of interests were in Somerset county in that year. Of course, that county is not in the census.

My people had been in counties that were in that census. Operative phrase: had been. Sigh… they’d left for Virginia and then North Carolina by then.

Judy,

Thanks for mentioning availability on FamilySearch.org!

One can access both volumes on FamilySearch.org by selecting the links at https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/155413

Robert Raymond

FamilySearch

Not exactly, Robert. For Volume 2, the message reads: “You do not have sufficient rights to view the requested object. Only a limited number of users can view this object at the same time, and viewers must be in the Family History Library, a partner library, or a Family History Center. If you are in one of these locations and are receiving this message, the user limit has been exceeded. Please try again later.” (Emphasis added.)

That’s good to know. I will get that fixed.

That’d be nice… 🙂

Judy, can you clarify…”congress intended to secure the bills by levying a tax on each colony according to a quota….”

What about the other colonies, besides Maryland, was there a census for them?

In some, yes, for sure. Brumbaugh’s preface to Volume I quotes the 1909 publication A Century of Population Growth in the United States, 1790-1900, as saying that both Massachusetts and Rhode Island did, “but most of the colonies failed to comply.” It’s worth checking everywhere.

Thank you! These are not easily “searched” on some sites, so it’s good to know they exist and go looking for them. I’m especially excited about some of the marriage records, beyond the Census!

To clarify, between the missing counties and counties that have only a small part included, most of the people in Maryland are not in this census.

For example, almost none of Baltimore county is in this census, just a small part of the Baltimore City area. Much of Frederick County is missing also.

However, I do agree it is worth checking the Brumbaugh books (not just the census part) , just in case.

Regarding the comments with Robert Raymond and FamilySearch website, I’m getting same response on several records collection in Virginia. I’d like to understand why, especially if they’re showing as on line and viewable, and they are county public records. Also, looking forward to your seminar in Brentwood, TN, in November, Judy G. Russell