From freeholder to householder

It changed, there in Tennesee, in 1809.

You can — if you’re like The Legal Genealogist and a bit of a law geek and like to read the laws — see the change right there in the laws.

It’s always fun for me, when I’m getting ready for a conference in another state, to see how the laws were and how they changed. So, in preparation for this weekend’s 29th Annual Genealogical Seminar of the Middle Tennessee Genealogical Society at the FiftyForward Martin Center in Brentwood,1 I’ve been looking at some Tennessee laws.

And it’s clear that something important changed there in Tennessee in 1809.

Up until that year, Tennessee basically followed the legal system that had been in place in its predecessor governments of North Carolina and then the Territory South of the River Ohio, more commonly known as the Southwest Territory.2

And, under those systems, jurors were freeholders.

Owners, if we go to the law dictionaries, of some recognized ownership interest in land (as opposed to leaseholders, or tenants).3

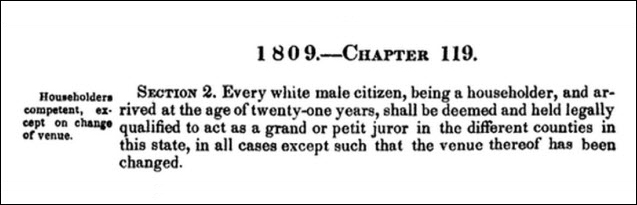

But, starting in 1809, the jury statute said something very different. Section 2 of Chapter 119 of the Laws of 1809 said:

Every white male citizen, being a householder, and arrived at the age of twenty-one years, shall be deemed and held legally qualified to act as a grand or petit juror in the different counties in this state…4

Note the very different word that shows up in this statute: householder, rather than freeholder.

And a householder was a very different beastie altogether in the law.

By definition: “The occupier of a house. More correctly, one who keeps house with his family; the head or master of a family. One who has a household; the head of a household.”5

What was going on that caused the change?

Two things, really: population growth and a real mess over land ownership.

We know that the population in Tennessee exploded during this time period. When Tennessee enumerated its population in 1795 in anticipation of petitioning for statehood, its census had reflected 77,262 inhabitants.6

We can’t do a real numbers comparison using the federal censuses because … sigh … “The territorial census schedules and the 1800 census were lost or destroyed. The 1810 census of Tennessee was also lost, except for Grainger and Rutherford counties” … and the 1820 census records are incomplete: “most East Tennessee counties are missing.”7

Looking at tax lists and other census substitutes, however, it’s clear that people were flooding over the mountains into Tennessee.

Making things a lot more complicated — land speculation was rampant:

In Tennessee’s pioneer days, settlers often had access to one form of currency: land. With the scarcity of cash money, land was the most important form of wealth, commerce and entrepreneurial activity in early Tennessee, as well as the chief magnet that drew people to this area.

First as a territory and then as a state, virtually all of Tennessee’s land passed from various governmental jurisdictions to private owners through grants of one sort or another. Politics and land speculation were closely intertwined and land issues were a leading concern of early government.8

And whenever you get politics and land speculators in the act, things get messed up really fast.9 Lots of folks ended up legally as squatters: being on the land, improving the land with houses and farms, and yet not clearly having title to the land until things got squared away down the road with laws recognizing the rights of preemption.

So… if you have people living in your jurisdiction and you want them to be available to serve on juries… but you’re not entirely sure if they own the land they’re living on, an easy way to make them eligible is to redefine what it takes to be a juror. Presto! No longer a freeholder as a requirement, but a head of a household.

And why do we care about this as genealogists? Because we tend to look at so many of those early jury lists to make distinctions among people. In so many early counties, we know that if this John Smith is on a jury list, he must have been a freeholder — a landowner of some stripe — and that’s going to distinguish him from that John Smith, the tenant farmer.

But not in Tennessee.

Not after 1809.

Our 1809 John Smith, living in Tennessee, may not have been a landowner at all.

Just another example of why we can only understand the records of the day by looking at the laws of the day.

SOURCES

- Yes, this is a location change from the Brentwood Library so make sure to check the website for directions. But note that the change in venue means a little more room, so walk-ins can be accepted, but without any guarantee that handouts or lunch will be available. ↩

- See generally Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Tennessee,” rev. 14 Nov 2017. ↩

- See Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 520, “freeholder” and “freehold.” ↩

- See §2, Chapter 119, Laws of 1809, in R.L. Caruthers & A.O.P. Nicholson, compilers, Statutes of Tennessee… (Nashville: James Smith, printer, 1836), 422; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 14 Nov 2017). ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 588, “householder.” ↩

- “Southwest Territory,” Tennesssee Encyclopedia of History & Culture, Tennessee Historical Society (http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/ : accessed 14 Nov 2017). ↩

- “Tennessee Census Records,” Tennessee Electronic Library, Tennessee State Archives & Library (https://sos.tn.gov/tsla : accessed 14 Nov 2017). ↩

- “Early Tennessee Land Records Available at the Library and Archives,” Tennessee State Archives & Library (https://sos.tn.gov/tsla : accessed 14 Nov 2017). ↩

- See generally the wonderful article on Tennessee land issues by Gale Williams Bamman, “This Land Is Our Land!: Tennessee’s Disputes With North Carolina,” originally published in the Tennessee Genealogical Journal, Vol. 24, Number 3, 1996, and reprinted with permission by the Tennessee GenWeb (http://www.tngenweb.org/ : accessed 14 Nov 2017). ↩

It’s interesting that in Ireland bout that time, and I assume the rest of the UK, landowning was **not** a requirement to be a freeholder. The importance of being a freeholder then was not to serve on juries but to vote in parliamentary elections. Landowners could vote of course, but tenants (1) who had a lifetime lease and (2) whose property was valued at 40 shillings or more, could also vote. They were naturally nicknamed “40 shilling freeholders.” Since voting was open and not secret the landowners encourage their more prosperous, reliable tenants to vote – for them of course. In later years the required value was raised to £10. I assume to keep the trash out.

See: Cavan Freeholders 1825

I guess the Tennessee laws were based on England’s but were modified for the occasion.

A lifetime lease might very well be treated as a life estate here in the US, and thus as a freehold and not a leasehold. See the definition of “freehold” in Black’s: “An estate in land or other real property, of uncertain duration; that is, either of inheritance or which may possibly last for the life of the tenant at the least, (as distinguished from a leasehold;) and held by a free tenure, (as distinguished from copyhold or villeinage.)”

Great article! I have several branches in Middle Tennessee. But I found this article when I searched for the difference between a freeholder and householder. I had ancestors living in Upper Canada that are listed in n a directory on a specified Lot before the original patent. The directory states “we have omitted the distinction in the Rolls between “Freeholder” and “Householder”. I think this means he had a household on the lot but it did not own the land.