… the war is over

It may be one of the things The Legal Genealogist loves best about genealogy.

Learning all those things about history that we never learned in school.

Our obligation as family historians, of course, is to put our families into the context of their time and place. So we need to learn all about their time and place — and not just the few key dates we had to memorize to pass history tests.

And today is the 203rd anniversary of an event few of us ever even heard of in school and yet is part of the story of so many of our families.

Let me set the stage here.

In June of 1812, after years of growing tensions, the United States declared war on Great Britain.1 The initial battles of the war were all in the upper north, in Michigan and Canada and Ohio.2

As the war dragged on, the scope of the war spread. In 1814, the British burned Washington, D.C. in September, the Battle of Baltimore took place — that’s the one we all know from the words of the Star Spangled Banner, written during the bombardment of Fort McHenry.3

And then the history bits we all learned in school: in January 1815, General, and later President, Andrew Jackson defeated the British at the Battle of New Orleans, and in February 1815, there’s a Peace Treaty that ends the war.4 So it was that pivotal defeat, with casualties on both sides, that brought the British to the peace table, right?

Um… not exactly.

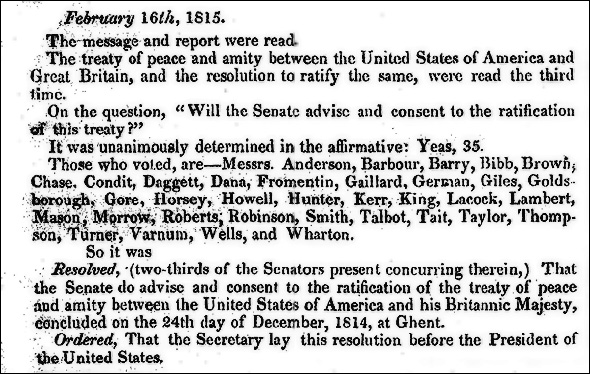

Oh, it’s true enough that the peace treaty ending the war was ratified by the United States Senate on the 16th of February 1815:5

But read the “Resolved” part of that ratification again: the treaty itself had been signed long before February of 1815 — and even well before the Battle of New Orleans was fought. Called the Treaty of Ghent, that peace treaty had actually been signed on Christmas Eve, 1814.6

The problem was… nobody on this side of the Atlantic knew about it until the American negotiators reached America with the news.

Exactly 204 years ago today, on February 11, 1815. (Thanks, Michael Stills, for the math correction…)

Now think about that for a minute.

An entire campaign fought, with casualties on both sides, because there were no transatlantic telephones, no internet, no broadcast news anchor standing outside the room where the negotiators were meeting.

No way to communicate that momentous news except by traveling across the ocean and making their way to the President, James Madison, who communicated it to the Congress.

That’s the kind of history we have to know, and get to learn about, to put our families into the context of their time and place.

Genealogy is so much fun.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “Oh, and by the way…,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 11 Feb 2019).

SOURCES

- “An Act declaring War between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the dependencies thereof, and the United States of America and their territories,” 2 Stat. 755 (18 June 1812). ↩

- See “War of 1812 Timeline of Major Events,” Public Broadcasting System (http://www.pbs.org/ : accessed 11 Feb 2019). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America, 2: 620 (16 Feb 1815); digital images, “A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774-1875,” Library of Congress, American Memory (https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/lawhome.html : accessed 11 Feb 2019). ↩

- “Primary Documents in American History: Treaty of Ghent,” Primary Documents in American History, Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/ : accessed 11 Feb 2019). ↩

Judy, 204 years ago? 1815 +204 = 2019

Dammit. I still can’t count. Fixed, and thanks.

I’ve had some great discoveries regarding the War of 1812. As you said, the early battles were in Michigan and Ohio. Several of my French-Canadian ancestors, who had settled Monroe Michigan become Americans when the Revolution ended, were members of the Michigan Territorial Militia in 1812. When the US Army General, William Hull, surrendered Fort Detroit essentially without a fight, the Regulars became POWs, but the militia were simply disarmed by the British and told to go home until exchanged. Years later, my 4th great grandfather tried to get reimbursed by the federal government for a horse, bridle, saddle and blanket and pair of spurs that he had lost to one of Tecumseh’s warriors. I haven’t found out yet if he ever got paid.

Those are the kinds of stories that make history come alive. Have fun chasing the claim!