From slavery to major landowner

Hers is an amazing story.

No matter how you look at it, the life of Bridget “Biddy” Mason is simply astonishing.

The bookends of her life set the stage: she was born into slavery in the Deep South in 1818; she died as a prominent citizen and landowner in California in 1891.1

Bridget, called Biddy, was enslaved by different people in her early years. Her last enslaver was Robert Marion Smith, a convert to the LDS church who took her and her children first to Utah and then to California.

But by 1851, when Smith and those he enslaved arrived on the west coast, California was a free state. He tried to move again, to Texas, but was stopped from taking those he’d enslaved out of the state by the Los Angeles County sheriff. In 1856, Biddy and 13 members of her family were declared free by the Los Angeles District Court.2

Now that alone is a story worth telling. But the other bookend is equally enthralling:

She continued working as a midwife and nurse, saving her money and using it to purchase land in what is now the heart of downtown L.A. There she organized First A.M.E. Church, the oldest African American Church in the city. Mason used her wealth, estimated to be about $3 million, to become a philanthropist to the entire L.A. community. She donated to numerous charities, fed and sheltered the poor, and visited prisoners. Mason was instrumental in founding a traveler’s aid center and an elementary school for black children.

Bridget “Biddy” Mason died in L.A. on January 15, 1891. She was buried in an unmarked grave in Evergreen Cemetery. On March 27, 1988, the mayor of L.A. and members of the church she founded held a ceremony, during which her grave was marked with a tombstone.3

And it’s how she got to that other bookend that intrigues reader Jeri Mae Rowley. “What property rights laws enabled a single black woman, Biddy Bridget Mason during the years 1850 – 1891, to become Los Angeles’s first Black female property owner?,” she asks. She was able to find “articles on married women’s California property rights–a legacy of Spanish law–but not single women.”

What Jeri is confused by is the problem we all grapple with as genealogists, of understanding the rights of women at various times in history. Married women in particular labored under enormous legal disadvantages for much of American history because of a concept called coverture: the legal disabilities a married woman labored under because her legal status merged into that of her husband.4

There are two key things to understand about Biddy Mason and her property:

• Women — whether married or not — could own property. They could buy it or inherit it or receive it as a gift. But married women — called feme covert5 — were limited in what they could do with the property they owned. In general, under many laws of the 19th century, they couldn’t sell it without their husband’s approval, he was the one who managed the property, and she couldn’t leave it to persons of her choice in a will.

Even in California, where Spanish law had applied and married women generally had more rights than in parts of the country where English common law applied, the husband was given the legal right to manage his wife’s separate property.6

• Single women — widowed, divorced or never married, like Biddy — didn’t labor under those same legal disabilities. Biddy and women like her had the legal status of feme sole7 — and when it came to property, their legal status was the same as men: they could buy, sell, dispose of by will and do anything else they wanted with their land.

Of course, the fact that Biddy Mason didn’t labor under the legal disabilities of a married woman doesn’t make her story one whit less inspiring: born into slavery at one bookend, and died a substantial landowner and one of the great philanthropists of 19th century California at the other bookend.

But the law worked in her favor twice: once when it provided her with the means to win her freedom and again when it gave her — an unmarried woman — the power to make her own choices as to her own land.

And the story she wrote by her own determination and grit between the bookends of slavery and philanthropy is a story worth telling again and again.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “Biddy’s bookends,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 25 Feb 2019).

SOURCES

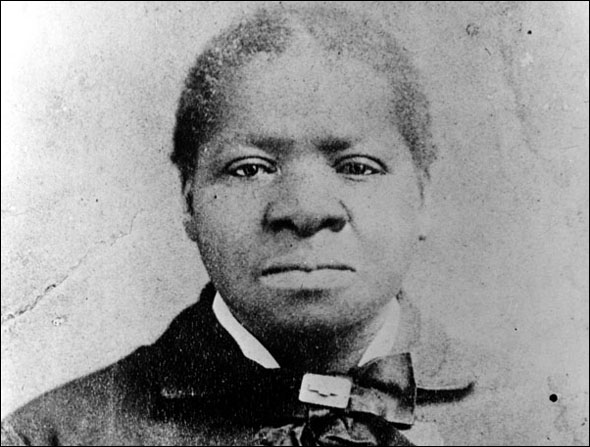

Image: Portrait of Biddy Mason (1818-1891), via Wikimedia.

- “Bridget ‘Biddy’ Mason,” People, National Park Service (https://www.nps.gov/ : accessed 25 Feb 2019). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- See Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 298, “coverture.” And see Chapter 15, “Of Husband and Wife,” in William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, Book I (The Right of Persons), 4th ed. (Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1770), 433-445; digital images, HathiTrust Digital Library (https://www.hathitrust.org/ : accessed 25 Feb 2019). ↩

- See Black, A Dictionary of Law, 483, “feme covert.” ↩

- See §6, Chapter 103, Laws of the State of California (San Jose : State Printer, 1850), 254; digital images, Office of the Chief Clerk, California General Assembly (https://clerk.assembly.ca.gov/ : accessed 25 Feb 2019). ↩

- See Black, A Dictionary of Law, 483-484, “feme sole.” ↩

Thanks for the legal research into single women property rights in California during the late 1800’s. Biddy Mason’s story has been the highlight of a very educational 2019 Black History Month.

Thank YOU for a great question!

I have included your blog in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

https://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2019/03/friday-fossicking-1st-march-2019.html

Thanks, Chris

Hi Judy, perhaps you’ve seen this…puts coverture on its ear:

https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300218664/they-were-her-property

The book has informed me in two ways: I’ve “discovered” a cluster of black and white married women in SC purchasing lots in early 1870’s. Seemed rather progressive to me considering coverture and my preconceived notion of what women would do in provincial Newberry. Curious about coverture and researching that, a librarian pointed out: 1868 SC constitution…which is so associated with rights for blacks.

Married Women’s real and personal property could not be taken for husband’s debts

See Article XIV miscellaneous: section 8

According to “They were property….” Coverture was not fully practiced…

See Chapter 2 They Were Her Property: White Women’s Property

Footnotes #75

So the married women who were purchasing property were part of an arc…not completely new. Anyway that’s my analysis, so far.

Statutes to protect the property rights of married women began as early as 1839 (Territory of Arkansas) and moved ahead full steam after the New York act (1848) which was often a model for other jurisdictions. These were just the first steps towards giving married women control of their own property, and we clearly have many vestiges of coverture well into the 20th century. But yes it began then.