Freedom and the draft: 150 years ago today

Two remarkable statutes became law 150 years ago today. The two legislative bodies that passed them sat less than 100 miles apart, and — whether directly or indirectly — both had to consider the same then-existing American practice: slavery.

Yet in terms of their causes and their effects, the two statutes could not have been more different, and the two legislatures might as well have been in different galaxies. One law set people free; the other conscripted the unwilling into bearing arms.

And the Civil War raged on.

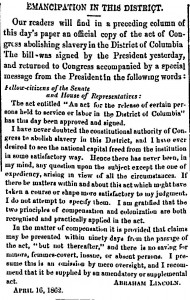

In Washington, D.C., on 16 April 1862, the District of Columbia Emancipation Act was signed into law by President Lincoln after having been passed by both houses of the United States Congress. This was the first formal federal statute outlawing slavery in any previous slaveholding area, and the first statute to touch on slavery at all since the 1854 passage of the act organizing the Nebraska Territory and allowing for the admission of Kansas and Nebraska as states “with or without slavery, as their constitution may prescribe at the time of their admission”.1The legislation provided for immediate emancipation of all enslaved persons within the District of Columbia, and forbade involuntary servitude of all kinds except for those convicted of crimes.2 Any person freed by the statute was entitled to receive a certificate of freedom from the clerk of the circuit court.3 The law made it a felony carrying a 5-to-20 year prison term for any person to kidnap or take a freed slave out of the District with intent to re-enslave or sell the person into slavery.4

Those loyal to the Union were permitted to file claims for compensation of up to $300 per slave.5 A supplementary act dated 12 July 1862 granted freedom to any enslaved person brought by an owner into the District after the Emancipation Act was in effect and allowed the former owners to file for compensation. If the owner didn’t act, the slave could apply on his or her own.6

The statute wasn’t a simple statement of freedom. It also carried with it a suggestion that the newly freed slaves weren’t entirely welcome to stay on in the nation’s capital. Section 11 of the Act provided for an appropriation of up to $100,000:

to aid in the colonization and settlement of such free persons of African descent now residing in said District, including those to be liberated by this act, as may desire to emigrate to the Republics of Hayti or Liberia, or such other country beyond the limits of the United States as the President may determine…7

This provision frightened many of the newly-freed slaves into believing that they were about to be forcibly removed from America and sent off to some unknown fate. Some fled the District, resurfacing only later when it became clear that forced colonization wasn’t part of the law.8

The records created as the result of this legislation — held by the National Archives — are simply fabulous. The statute called for the filing of “a statement in writing or schedule shall be filed with the clerk of the Circuit court for the District of Columbia, by the several owners or claimants to the services of the persons made free or manumitted by this act, setting forth the names, ages, sex, and particular description of such persons.”9 More than 1,125 claims were filed, describing more than 3,100 slaves.10 Emancipation papers for the freedmen are in the District Court papers at the National Archives.11

On the other side of the scale, in Richmond, Virginia, on 16 April 1862, the Confederate Congress passed and President Jefferson Davis signed the first conscription act of the Civil War. It provided that:In view of the exigencies of the country, and the absolute necessity of keeping in the service our gallant army, and of placing in the field a large additional force to meet the advancing columns of the enemy now invading our soil: Therefore

The Congress of the Confederate States of America do enact, That the President be and he is hereby authorized to call out and place in the military service of the Confederate States, for three years, unless the war shall have been sooner ended, all white men who are residents of the Confederate States, between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five years, at the time the call or calls may be made, who are not legally exempted from military service.12

Conscription was bitterly resisted in the South, particularly among those on whom its burdens fell most strongly. Since many wealthy landowners were exempt, “those who were not favored with position and wealth … grudgingly took up their arms and condemned the law which had snatched them from their homes…”13 The constitutionality of the statute was challenged as well, with Governor Brown of Georgia taking the position that it violated states’ rights.14

In part because of resistance to conscription, in October 1862, the upper age for conscription was raised to 45,15 although the initial call-up pursuant to the act only affected men between the ages of 35 and 40. By the summer of 1863, however, the reserves aged 40 to 45 had been called out,16 and by February 1864, the upper age for the draft had been raised to 50.17

Like its Union counterpart, this Confederate statute produced records by the ream. Since units that volunteered before the start of mandatory conscription were permitted to choose their own officers, both recruiting documents and muster rolls may exist documenting the elections and organization of the units.18

Because the conscription statutes provided for exemptions, records of county courts throughout the South may produce documents of those seeking exemptions from conscription. Later in the war, Enrolling Offices in each county were to review requests for exemptions and special details;19 records often still exist at the county level.

For those whose efforts to avoid service failed, Compiled Military Service Records for Confederate Troops are held by the National Archives20 and available online at services like Ancestry.com and Fold3.com. Other possible sources of conscription records include the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond and state archives such as the Library of Virginia and North Carolina State Archives, just to name two.

Two very different actions, 150 years ago today. Freedom on one hand. Conscripted military service on the other. And about the only thing the two have in common is the one thing we can all be grateful for today: the creation of records we can all use — no matter what side of the Mason-Dixon line our ancestors fell on.

SOURCES

- Act to Organize the Territories of Nebraska and Kansas, 10 Stat. 277, § 1. ↩

- An Act for the Release of certain Persons held to Service or Labor in the District of Columbia, 12 Stat. 376, § 1. ↩

- Ibid., § 10. ↩

- Ibid., § 8. ↩

- Ibid., §§ 2-5. ↩

- 12 Stat. 538. ↩

- An Act for the Release of certain Persons held to Service or Labor in the District of Columbia, 12 Stat. 376, § 11. ↩

- See Damani Davis, “Slavery and Emancipation in the Nation’s Capital: Using Federal Records to Explore the Lives of African American Ancestors,” Prologue, Spring 2010, Vol. 42, No. 1, online edition (http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/ : accessed 15 Apr 2012). ↩

- 12 Stat., 376, § 9. ↩

- See Records of the Board of Commissioners for the Emancipation of Slaves in the District of Columbia, 1862–1863; Records of the Accounting Officers of the Department of the Treasury, Record Group (RG) 217; National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. ↩

- Records of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia Relating to Slaves, 1851–1863; Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21; NA-Washington. ↩

- W.W. Lester and Wm. J. Bromwell, A Digest of the Military and Naval Laws of the Confederate States, From the Commencement of the Provisional Congress to the End of the First Congress Under the Permanent Constitution (Columbia, S.C. : Evans and Cogswell, 1864), 57-58; electronic edition, Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (http://docsouth.unc.edu : accessed 15 Apr 2012). ↩

- Albert Burton Moore, Conscription and Conflict in the Confederacy (1924, reprint, Columbia, South Carolina : University of South Carolina Press, 1996), 18. ↩

- Ibid., 23-24. ↩

- Ibid., 140-142. ↩

- Ibid., 207. ↩

- Ibid., 308. ↩

- See e.g. Jeffrey C. Weaver, 10th and 19th Battalions of Heavy Artillery, Virginia Regimental History Series (Lynchburg, Va. : H.E. Howard, 1996), 2. See also, again as an example, Muster roll, Company B, 10th Virginia Heavy Artillery, undated; Confederate Military Records, box 10, folder 2; accession 27684; Military Affairs Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond; digital image by J. Dondero, 12 October 2010; copy in Judy G. Russell’s files. ↩

- See Confederate States of America, Bureau of Conscription, Circular No. 8, March 18, 1864; Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (http://docsouth.unc.edu/imls/circular8/circular.html : accessed 15 Apr 2012). ↩

- For descriptions of each state’s records, see generally Pamphlets on Microfilm Publications in the National Archives Library: Civil War Compiled Service Records, Archives.gov (http://www.archives.gov/ : accessed 15 Apr 2012). ↩

Challenging times indeed – and lots of records for people to research. Thanks for this very interesting juxtaposition of law anniversaries.

Thanks for the kind words, Celia!