Name a DNA beneficiary

These are tough times, no doubt about it.

And so The Legal Genealogist has to raise a tough question: are you ready if the worst happens with respect to any DNA test you’ve taken or where you manage the results?

Do you — and your testers — have an estate plan to cover what will happen to your test results and any remaining sample?

This has always been an issue in DNA testing, since we’ve always advised people to “test the oldest generation first.” That only makes sense, particularly in the context of autosomal DNA testing, when every generation is impacted by what’s called recombination: the random jumbling of genes that occurs before half (and only half) of those randomly-jumbled pieces gets passed on by each parent to the next generation.1

But the very fact that we have tested the oldest members of our families has long meant that we needed to plan for the future, and for access to those results, when the inevitable happened and we lost those oldest members of our families.

That planning only takes on an additional degree of urgency today, in a time of crisis that disproportionately impacts those oldest members of our families … often including ourselves.

There’s no question but that the vast majority of those who test want their results to be available and accessible forever to their family members and especially to the family genealogists who’ve often cajoled them into testing and even paid for the tests. So how do we make sure this is done? In other words, how do we do estate planning for our DNA results, the way we do when we sit down and write wills for our other property and effects?

This isn’t a new problem, and I’ve written about it before.2 But it’s still a problem that only one DNA company has addressed — and that all companies and all DNA testers need to address. And, because particularly right now we’re all getting a reminder that there are no guarantees in life, it’s something we as testers have to address right now.

Only Family Tree DNA has tackled the question of making sure that each person who tests can say what should happen with access to his or her account into the future, by allowing each person who tests to choose and specifically identify a beneficiary for our DNA samples and results. The solution there is a fill-in-the-blanks system, backed up by a printed form to be signed and notarized and put with our other legal effects.

While I’d prefer an all-digital system, it’s at least a system in place, and I can’t recommend strongly enough that (a) every DNA testing company (are you listening, AncestryDNA? 23andMe? MyHeritageDNA? LivingDNA?) create a simple online system to allow testers to indicate their estate plan for DNA samples and results and (b) every person tested use whatever system exists to say what they want done to guarantee future access according to that plan.

Since I’ve tested with Family Tree DNA, by simply filling in a few bits of information, I can set things up so that someone I choose can be:

the sole beneficiary to (my test kit), my Stored DNA, DNA Results, and FamilyTreeDNA account, to do all things required. For that purpose my beneficiary may execute and deliver, or amend, correct, replace all documents, forms, consents or release, tests and upgrades, and may do all lawful acts which may continue my involvement with FamilyTreeDNA.com.3

If you’re a Family Tree DNA customer, here’s how to do it. First, log in to your Family Tree DNA test results and, on the dashboard page, drop down the menu to the right of the account name and choose Account Settings:

Click on that link, and you’ll go to this page, and note the arrow pointing to the Beneficiary Information tab:

Click on that tab, and you’ll go to this page where you can fill in the name, telephone number and email address of your designated beneficiary and make sure to Save that entry. Then click on the Print Form link shown by the arrow:

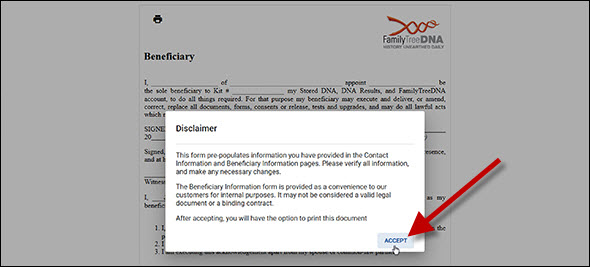

That will take you first to this interim box where you must accept its limits — including the fact that it may not be accepted as legally binding in your state:

Click on the Accept button, and you’ll go to the form itself — prepopulated with the information you entered on the designation page — and the arrow points to the Print button so you can print it out:

That of course leaves us with two problems.

First, what if I’ve tested with other companies? My suggestion is to do what I’ve done: I’ve taken the Family Tree DNA form, and changed the language, replacing all the references to Family Tree DNA with each of the other company names, and all the references to my kit number and the like with appropriate information about my test results from the other companies. And I’ve given my beneficiary the legal authority to continue to access my results and accounts at those other companies if something happens to me.

Second, these forms really should be notarized, and how — in this time of social distancing — are we supposed to do that? The reality is, we can’t. So my suggestion at the moment is to have every adult member of the tester’s household witness the form, to be able to testify later to the tester’s wishes if it ever becomes an issue. For those who live alone, my suggestion is to recreate the form in its entirety in our own handwriting — writing every single word by hand — to create in effect a holographic codicil4 to our estate plan.

Now I can’t guarantee the other companies will honor one of these forms, or that any state will recognize one as binding and legal. But it’s the best many of us can do right now — and a lot better than doing nothing.

Because if something does happen to me, it may well be more important to my extended family to have my genetic legacy than any other legacy I might possibly leave them.

I’m doing everything I can to ensure that that legacy does get passed on, by doing estate planning for my DNA.

How about you? What’s your estate plan for your DNA?

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “DNA in a time of crisis,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 5 Apr 2020).

SOURCES

- ISOGG Wiki (http://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Recombination,” rev. 14 Apr 2019. ↩

- See Judy G. Russell, “Estate planning for DNA,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 20 Aug 2017 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/ : accessed 5 Apr 2020). See also ibid., “DNA ownership,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 14 Sep 2014. ↩

- Family Tree DNA beneficiary designation printed form, Family Tree DNA (https://www.familytreedna.com/ : accessed 5 Apr 2020). ↩

- Holographic simply means entirely handwritten. See Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 576, “holograph.” And a codicil is a written instrument amending, or altering, a will, but not revoking it in its entirety. Ibid., 216, “codicil.” ↩

I just want to say thank you! I had never thought about this complication before. Stay well and safe!

What if there’s pretty much no one who would want to be your beneficiary on this? Lots of family members just aren’t interested. I’m an only child and I don’t have children. I don’t have any first cousins because my parents were only children. My closest DNA relatives are my parents’ cousins and their children, my 2nd cousins. I don’t think they want to be saddled with this. I can’t imagine my husband’s family wanting anything to do with it. I have thought about having samples/data destroyed upon my death (if they do that, and I’d have to leave explicit instructions), yet I hate to take away that future research benefit for others. Even if no one’s administering my kits, I don’t necessarily mind if the data stays in the databases as long it’s being used for genealogy research that will hopefully help someone else out. Admittedly, it’s weird knowing your DNA data will be in labs long after you’re gone. But this is what we signed up for.

If you’re a member of any project, see if the project administrator would be willing to take it on.

One person found that her bank branches’ notary with prior arrangements , did a notarization via the drive through window, with the witnesses along in the car…

So how can I get a copy of this form if I am not a customer. I’ve tested with 23 andMe and Ancestry.

You’ll need to use a different form, then. And simply writing up your wishes in plain English should be as good.

Is it important to do this for the companies we’ve not tested with, but uploaded results to? (Think GEDmatch and other testing companies.) I’m trying to think of a reason.