Mason Lee’s will

So The Legal Genealogist gets a request from Charlie Purvis:

Would you please give us an article discussing & summarizing an 1827 case – Heirs at Law of Mason Lee vs Executor of Mason Lee. (Marlboro County, SC)

Would I? Would I ever! I mean, hey, how many times do you get to consider the issue of just how crazy you have to be, to be considered too crazy?

Now we all know as genealogists that one of the requirements for a legal will is that the person making the will — the testator1 — has to be of sound mind (compos mentis in legal Latin).2That’s why we see that introductory language in wills that the person is “of sound mind” or “of sound mind and memory” or, in the case of Mason Lee, “of perfect mind, memory, and understanding.”3 If the person isn’t of sound mind — if he’s non compos mentis4 — then the will won’t hold up.

The legal issue is often said to be one of testamentary capacity — or “(t)hat measure of mental ability which is recognized in law as sufficient for the making a will.”5

So… just how crazy do you have to be, to be too crazy to make a valid will? That was the question a South Carolina jury had to contend with in Mason Lee’s case, which reached the South Carolina Court of Appeals in the January term of 1827.

And the answer, in a nutshell, according to this case, is: really, really crazy. In fact, you can go ahead and be really, really crazy if you’d like — as long as you’re not really, really crazy on the exact day and at the exact time when you sign the will.

The facts of the case

Mason Lee was born, most likely in North Carolina, around 1770.6 By his later years he was a wealthy planter with an estate valued in the neighborhood of $50,000. He died in what became Marlboro County, South Carolina, and his will was offered for probate in the Marlboro District Court of Ordinary in 1821.7

He executed the last version of his will in July 1820. Like every one of the prior versions, he left nothing to any of his relatives: nieces and nephews by his two sisters or his twin sons born out of wedlock. In this last will, he left his estate to be divided equally between the states of South Carolina and Tennessee.8

Now this is all nothing unusual, right? People leave their estates to non-family members all the time — to charity, to homes for stray cats, even to their dogs. So what was the big deal here?

The fact was, Mason Lee was… well… a little odd. The court called him eccentric. You and I might choose perhaps stronger words. Here’s a brief summary of what the jury in this case learned about him:

• Mason seemed to be a pretty normal guy until he was hit by lightning around the age of 30 while still living in North Carolina. He then moved to Georgia and “began to discover the peculiarities which ever after marked him.” He killed “his negro” (slave or free wasn’t expressly stated but the use of the phrase suggests a slave) in Georgia and fled to South Carolina.9 He lived in fear that one of his relations — Baker Wiggins — was trying to kidnap him and take him back to Georgia.10 And, he thought, the Wigginses were using spells on him.11

• Except for the Wigginses, he was on good terms with his relatives but didn’t want to leave his estate to any of them because, if he left them property, they would want him dead or try to injure him. “His reason for not providing for one son was, that although he was a twin brother of the other, he was the father of only one of them.” He left his estate to the states because he was convinced that the Wiggins relations were determined to break his will and only the states could afford to defend the suit. He didn’t know anyone in Tennessee, so he designated “one of the first rate Baptist preachers of that state as his executor, without naming him.”12

• “He believed that all women were witches, and would not sleep on a bed made by a woman … that persons at a distance could exercise an influence over his mind and body … that spells were laid for him … that he could be bespelled if he made water on the ground (and so) carried a tin cup in his pocket (to avoid) making water on the ground.” He cut off parts of his shoes and drilled holes in his hat to drive the devil from his feet and head.13

• “In the day time, neglecting his business, he dozed in a hollow gum log for a bed, in his miserable hovel; and at night kept awake contending against the devil and witches. He fancied at one time that he had the devil nailed up in a fireplace at one end of his house …”14

• “He believed that he had conversed with God; and said he had met him in the woods, and promised him that if he would let him get rich, he would live poor and miserable all his life; and he seemed to have kept his promise. When he lived in Pedee swamp, … his hogsty was directly before his door … which was not high enough to admit him erect. His bed was a split hollow gum log … He had no chair or table in his house, nor platter, dishes, or plates. …”15

• “His clothes were of his own make. They had no buttons. The pantaloons were wide as petticoats, without any waistband, and fastened round him by a rope. … He was remarkably filthy, not cleaning his clothes for months.”16 He routinely cut off the tails of all hogs and cows and cut off the ears of his horses and mules.17

• When, late in his life, he was given a house 12 feet square, he complained that it was “too large.” He rebuilt it “three feet wide, five feet long, and four feet high. In this kennel he (ate), slept, and dozed away his time.”18

Now to be fair there was evidence that he was “sane and perfectly capable of managing his business” and merely eccentric, at least when sober, and that he’d sobered up for two or three whole weeks before executing the will eventually offered for probate. And the three witnesses to the will — “respectable men, living near him, (who) knew him well … swore positively to his capacity at the time of its execution, and to the fact of his keeping sober for that purpose.”19 Others regarded him as “a very singular man, but not insane…”20

The law according to the judge

Based on all the evidence and the law as it stood at the time, the judge charged the jury that “the will could only be invalidated by proof of an existing insanity at the time of making it …” In particular, the judge cautioned that “it was not … every man of a frantic appearance and behavior who is to be considered a lunatic …, but he must appear to the jury to be non compos mentis … at the moment when the act was done.” He went on: “It could not be denied that it was a strange will, and if not the production of an insane mind, it was no doubt that of a very eccentric one. (But) the law puts no restriction on a man’s right to dispose of his property in any way in which his partialities, or pride, or even caprice may prompt him, if he does not infringe any rule of policy.”21

The judge finally told the jury that “in exercising their own judgment on this difficult and mysterious subject, if the testator was not proved to be insane by full and unequivocal evidence, they were bound to find in favor of his sanity. A rational state of mind is the natural state of every man, and until there is full proof of insanity the law presumes that every man is in a rational state when he does any act either civil or criminal.”22

And the jury’s decision? “The jury found a verdict in favor of the will.”23

The law according to the appeals court

The heirs at law appealed and asked for a new trial. They were represented by three of the biggest legal names in South Carolina; the estate by two future U.S. Senators. The appeals court disposed of the case in a single paragraph, concluding that the judge’s charge was correct, and that the issues were “fairly and correctly submitted to the consideration of the jury.”24

In other words, as long as you’re not really really crazy when you sign your will, you can go ahead and be as crazy as you want the rest of the time.

And, by the way, that rule of law — that a testator is presumed to be sane and only the most compelling evidence to the contrary at the time the will is executed will invalidate a will — is still the law of South Carolina today.25

The rest of the story

Now you know better than to think this is all of the story, right? A big estate with land and slaves and cash is just too much to let go without more of a fight. And the heirs at law didn’t let it go. They went to the Legislature with a petition to set aside the will anyway.26

And they won. In December 1829, the South Carolina Legislature “parted with its rights & interest in the estate of the said Mason Lee” in favor of the heirs at law. It isn’t clear whether the heirs tried the same gambit in Tennessee; what is clear is that Tennessee didn’t give up its share of the estate but rather sold it to one Robert B. Campbell (himself a member of Congress from South Carolina), who then joined with the heirs at law in a partition action in 1831.27

Today, there stands an Historical Marker near Blenheim in Marlboro County, South Carolina. The front of the marker reads:

Mason Lee (1770-1821), a wealthy Pee Dee planter known for his eccentricities, is buried in old Brownsville graveyard two miles south of here. He believed all women were witches and that his kinsmen wished him dead to inherit his property. He felt they used supernatural agents to bewitch him and went to great extremes to avoid these supposed powers.28

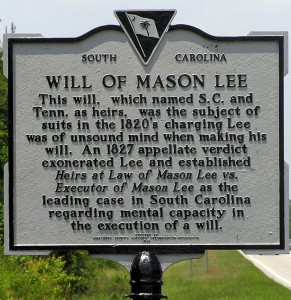

And on the reverse side:

This will, which named S.C. and Tenn. as heirs, was the subject of suits in the 1820’s charging Lee was of unsound mind when making his will. An 1827 appellate verdict exonerated Lee and established Heirs at Law of Mason Lee vs. Executor of Mason Lee as the leading case in South Carolina regarding mental capacity in the execution of a will.29

Mason Lee’s grave itself is in the old Brownsville Church Cemetery in Marlboro County, South Carolina.30 And with so much of his estate having passed into the hands of the Wiggins relations, you just have to believe he’s there spinning in it even today.

SOURCES

Image by Paul Crumlish, 7 May 2010

- “One who makes or has made a testament or will; one who dies leaving a will.” Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 1166, “testator.” ↩

- Ibid., 239, “compos mentis.” ↩

- See Lee’s Heirs v. Lee’s Executors, 15 S.C.L. (4 McCord) 183, 184 (1827). ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 820, “non compos mentis.” ↩

- Ibid., 1166, “testamentary capacity.” ↩

- See Lulu Crosland Ricaud, “Marlboro Man Lived in Fear of Witches,” The (Charleston S.C.) News and Courier, 17 Apr 1949, p. 6C, col. 1. The court opinion says he was brought up in North Carolina. Lee’s Heirs v. Lee’s Executors, 15 S.C.L. at 188. ↩

- Ibid., Lee’s Heirs v. Lee’s Executors, 15 S.C.L. at 183. ↩

- Ibid. at 183-185. ↩

- Lee’s Heirs v. Lee’s Executors, 15 S.C.L. at 188, 191-192. ↩

- Ibid. at 191. ↩

- Ibid. at 185. ↩

- Ibid. at 189-190. ↩

- Ibid. at 186. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. at 187. ↩

- Ibid. at 187-188. ↩

- Ibid. at 189. ↩

- Ibid. at 188. ↩

- Ibid. at 190-192. ↩

- Ibid. at 193. ↩

- Ibid. at 193-195. ↩

- Ibid. at 196. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. at 197. ↩

- An attempt to get the case overturned was rejected in In re Washington’s Estate, 212 S.C. 379 (1948). It was cited as good law as recently as 1997. Weeks v. Drawdy, 329 S.C. 251, 264-265 (1997). ↩

- Ricaud, “Marlboro Man Lived in Fear of Witches,” The (Charleston S.C.) News and Courier. ↩

- Cheraw District Equity Bills 1836 #50, Campbell v. Wiggins; South Carolina Dept. of Archives and History; transcription by L. Hunter, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 23 May 2012). See also Ricaud, “Marlboro Man Lived in Fear of Witches,” The (Charleston S.C.) News and Courier. ↩

- “Grave of Mason Lee / Will of Mason Lee,” The Historical Marker Database (http://www.hmdb.org : accessed 23 May 2012). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Old Brownsville Church Cemetery, Marlboro County, SC, Mason Lee marker; digital image, Find A Grave (http://findagrave.com : accessed 23 May 2012). ↩

You always have such captivating stores. Who knew law could be so interesting? No, I think it’s just your writing that makes it interesting. Keep up the great stores.

Thanks for the kind words, Tina, but there are a LOT of cases that are this interesting. Really!