Oh yes there are…

A careful review of the grantor and grantee indexes of deeds in Winston County, Mississippi, says there are no deeds to or from William M. Robertson or his son Gustavus Boone Robertson between 1841 and 1860.

To which The Legal Genealogist — 3rd great granddaughter of William and 2nd great granddaughter of Gustavus — says phooey.

From the get-go, it always seemed to me there had to be at least one deed. After all, we knew that William M. Robertson had acquired land from the federal government by purchase in January 1835,1 with the patent issued in 1841.2 And we knew that the Robertsons had moved to Attala County, Mississippi, by 1860.3

So when the Robertsons left — or at least at some time after they left — that land had to have been transferred to someone.

But — the grantor and grantee indexes said — nope, not by the Robertsons. Or Robersons. Or Robinsons. Or any other alternate spelling of any of the family names.

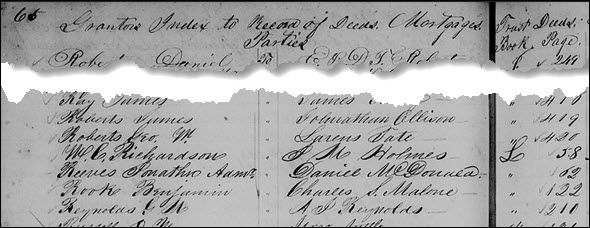

And specifically not any deeds by either of the Robertsons recorded in Winston County Deed Book L.4

I mean you can see it right there: four deeds recorded in Deed Book L by grantors with surnames starting with R, and none of them even close to Robertson.5

To which The Legal Genealogist repeats: phooey.

Oh yes there are deeds.

And they’re there in Deed Book L.

On page 348, W. M. Robertson to James Rodgers, a deed dated 4 January 1851 and acknowledged 11 January 1851, transferring the same 40.02 acres of land he got from the federal government through that 1841 patent. The sales price: $125.6

And, even better, on page 349, G. B. Robertson and wife “Isabela” to James Rodgers, a quit claim dated 11 January 1851 by which the younger Robertsons gave up any claim to an 80-acre tract of land next door to William’s land for $40.7

So they’re there, for sure.

The problem: they’re not indexed.

Which ought to take us back to first principles: we don’t rely on indexes whenever the underlying records survive and can be reviewed.

No deeds indeed.

Phooey.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “No deeds, indeed!,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 19 Aug 2023).

SOURCES

- Winston County, Mississippi, Tract Book, 1835-1910, p.86; digital images, DGS film 008630976, image 49, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org/ : accessed 19 Aug 2023). ↩

- William M. Robertson (Winston County, Mississippi), land patent no. 13267, 27 February 1841; “Land Patent Search,” digital images, U.S. Bureau of Land Management, General Land Office Records (https://glorecords.blm.gov/search/default.aspx : accessed 19 Aug 2023). ↩

- 1860 U.S. census, Attala County, Mississippi, Township 14, Range 8, population schedule, p. 76 (penned), dwelling 455, family 494, G B Robertson family; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 19 Aug 2023); citing National Archive microfilm publication M653, roll 577. ↩

- Winston County, Mississippi, Index to Deeds, 1835-1854 (through Deed Book M), arranged alphabetically by surname and then by deed book number; digital images, DGS film 008630976, image 49, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org/ : accessed 19 Aug 2023). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Winston County, Mississippi, Deed Book L: 348, Robertson to Rodgers (1851); digital images, DGS film 008316852, image 183, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org/ : accessed 19 Aug 2023). ↩

- Ibid., Deed Book L: 349, Robertson to Rodgers (1851). Nothing in the records explains what interest Gustavus and Isabella might have had in that next-door tract. Given the tract size and price, I suspect they had a leasehold, a right of first refusal or something of the sort, but not any ownership interest. ↩

Hi Judy, I had trouble following the dates that you provided from page 348. Are they all from 1841?

Thank you!

Ooops. Corrected, thanks. The deed is 1851, acknowledged 1851, transferring land acquired in 1841.

A belated deed question. When a deed in recorded in the deed book , does the presence of a signature in the book (as opposed to a signature with “his mark X”) mean that the original deed also had a signature? (Husband had an X, wife did not). I’m trying to separate two men of the same name- if no X means a signature then ✅

It should mean there was one, but you’d have to be careful in asserting it as fact. Clerical error is always a possibility.

So, if there are several deeds, recorded at different times with consistent signatures or Xs, that may be assertable fact?

We have a major record set that is most used in the form of a stand-alone index. Tucked away in the fine print it says it covers only 75% of the available records. They exist in other forms including microform but there is no pointer in that index as to how to find them. As a dinosaur genealogist I had to use those old forms. (CAUTION – chemistry has caught up with some of them and they are just dead celluloid now.)

So, the message to stuck newbies is – find a fossil – and ask them how they researched those records. You may just get around your problem area.

A very common thing is that deed indexes made much after the fact (like in 1900) do not index any of the personal property transfers, including bills of sale for enslaved people, or other personal property like household goods or livestock, etc. By that time, those transactions were not relevant, and so the indexer simply skipped over them. Page by page, or start with the in-volume indexes that many books had. Even if it’s only grantor, you can skim the grantee column for the whole alphabet. Lots of buried stuff!!

I would say all indexes have errors and the errors can be of various types. Omission from the index is but one type of error. Transcription errors are probably the most common errors. In some handwriting styles L and S can be confused, J and T, even P and T.

In addition the transcription error may by in the reference and not the name, so the index points to the wrong document.

In some cases the index is all you have, as the original records have been lost.

Indexes are very useful and save a lot of time. However, I agree with your point that not in an index does not mean not in the records.

Electronic indexes have the advantage that they can be updated reasonably easily, whereas paper (or particularly microfilmed paper) indexes generally do not get updated.