Uh oh! It’s the Police!

It’s one of genealogy’s most frustrating moments: knowing that a record ought to exist, and not being able to find it.You know there haven’t been any courthouse fires affecting the records you want. You know there had to have been records of the type you want. You even know the records from the county you’re interested in have been microfilmed for the time period you want. And you still can’t find it.

Sometimes, the reason is as simple as not knowing the name of the official body that would have created those records at that time in that place.

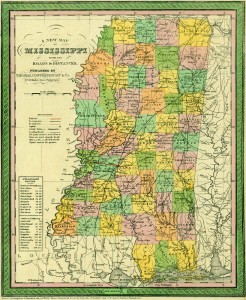

Case in point: road orders from Mississippi in the 1830s-1860s, the time when many of the counties where we research today were formed in that state.

Now anybody who’s ever dealt with road orders knows how incredibly valuable they can be for genealogists. Early American jurisdictions didn’t have Departments of Public Works to lay out and build roads and bridges and causeways. Instead, it was a civic duty shared among all the early citizens.

In the usual case, some public body — often the county court and/or local justices of the peace — would appoint an overseer who had supervisory authority over the hands of the neighborhood. The hands, basically, included everybody who lived on or near a road who could be ordered to turn out and help clear or build or maintain a road or bridge or causeway.

The official documents naming an overseer and, often, also naming the hands assigned to that overseer are generally known as road orders. And finding an ancestor’s name on a road order can be a genealogical jackpot. It can help distinguish between two men of the same name since it tells you this man lived on or near that road and near everyone else named in the order. It can fill in gaps between censuses by naming sons as they came of age to work on the roads. It can be used in so many ways.

So road orders are always among the first records I want after census and tax records, and when I went looking for them in the counties of Mississippi where my people hailed from, I couldn’t find ’em. Couldn’t find anything that sounded even remotely like ’em. Couldn’t even find a county governing body that might have created ’em.

And that’s because the official name of the public body in charge of the roads in Mississippi counties between 1832 and 1868 was the Board of Police. And the records are often catalogued as records of the Police Court.

Don’t go looking for that term in the legal dictionaries. You won’t find it. Look instead to the Constitution and statutes of Mississippi for the time.

The Mississippi Constitution of 1832 provided that:

The qualified electors of each county shall elect five persons for the term of two years, who shall constitute a board of police for each county, a majority of whom may transact business, which body shall have full jurisdiction over roads, highways, ferries, and bridges, and all other matters of county police; and shall order all county elections to fill vacancies that may occur in the offices of their respective counties: The clerk of the court of probate shall be the clerk of the board of county police.1

The constitutional provisions were then put into effect with the adoption of a statute defining the powers of the Boards of Police.2 It gave the Boards of Police “all such jurisdiction as is at present vested in the county courts of each county”3 and required the boards “to divide the public roads into precincts or districts (and) direct what persons shall work on each road…”4

Between those two grants of authority, the records of what came to be called the Police Court are wide ranging, including not just the road orders but much more, ranging from tavern licenses to land sales to registering stock marks to supervising elections.5

I have to admit, it was worth the aggravation of having to hunt to find the records for what the statute tells us about the responsibilities and duties of our Mississippi ancestors even if we can’t find a specific Police Court record with their names on it. The law provides, in part:

• That “no person shall be compelled to work on more than one road, nor more than six days in any one year.”6

• That “all free male persons over the age of sixteen and under fifty years of age” were subject to road duty, along with male slaves, and that road workers were required to “bring with them such tools to work with on the road” as the overseer of the road directed.7

• That the overseers could “receive on the roads the labour of able bodied female slaves, in lieu of the labour of male slaves.”8

• That an overseer who let a road or bridge be out of repair for more than 10 days “unless hindered by extreme bad weather” could be fined $10 for every offense.9

• That all public roads had to have mile markers marking “the number of miles from the court-house or principal town” in the county10 and road signs at every cross roads including the distances to the towns.11

• That public roads had to be “at least ten, and not more than thirty feet wide” and any causeways had to be “at least sixteen feet wide.”12

• That road workers could be called out for more than six days a year if a road, causeway or bridge was damaged and “dangerous for travellers to go over.”13

• That anybody who felled a bush or a tree into a public road had 24 hours to remove it or be fined $2 for every 24 hours the road was obstructed.14

• That any tolls charged on ferries, roads or bridges had to be approved by the Board of Police.15

• That the Board of Police could allow a land owner to put up a gate on a road through his property, but not on a road used by the United States mail.16

Wonderful stuff to add color to a family history, isn’t it?

Now the term didn’t stay in use in Mississippi for very long. The state changed the name of this official body from the Board of Police to the Board of Supervisors in the Constitution of 1868.17 And, by the way, Mississippi wasn’t the only state to use that kind of terminology. In Louisiana, a Police Jury was and is “the board of officers in a parish corresponding to the commissioners or supervisors of a county in other states.”18 Some 41 of Louisiana’s 64 parishes today are governed by a Police Jury.19

So the moral of this story is: if you can’t find the road orders anywhere else, call the cops. Or at least the Police.

SOURCES

- Article IV, § 20, Mississippi Constitution of 1832; Mississippi History Now (http://mshistorynow.mdah.state.ms.us : accessed 7 Jun 2012). ↩

- “An Act, to establish Boards of Police, and define their powers and jurisdiction, and for other purposes,” Laws of the State of Mississippi, … 1824-1838 (Jackson : p.p., 1838), 385-399; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 7 Jun 2012). ↩

- Ibid., § 3. ↩

- Ibid., § 10. ↩

- See e.g. “Police Court Records, 1836-1852,” Old Tishomingo County, Prentiss County Genealogical and Historical Society (http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~mspcgs/Index.html : accessed 7 Jun 2012). ↩

- “An Act, to establish Boards of Police…,” Laws of the State of Mississippi, … 1824-1838, § 10. ↩

- Ibid., § 11. ↩

- Ibid., § 13. ↩

- Ibid., § 15. ↩

- Ibid., § 17. ↩

- Ibid., § 19. ↩

- Ibid., § 25. ↩

- Ibid., § 31. ↩

- Ibid., § 32. ↩

- Ibid., § 38. ↩

- Ibid., § 47. ↩

- Article VI, § 20, Mississippi Constitution of 1868; Mississippi History Now (http://mshistorynow.mdah.state.ms.us : accessed 7 Jun 2012). ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 907, “police jury.” ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Police Jury,” rev. 31 Mar 2012. ↩

Thank you for sharing this very helpful research method; I will be collecting state constitutions for ancestral localities more often now! 🙂

Both constitutions and laws, Jenny! Well worth a review any time you’re researching in an area.

Wow – my head whirls, Judy – an entirely new set of records I’d never even thought of researching alongside the land grants/deeds. Makes sense. But I had never heard of “road orders” before. Thanks for such an informative post!

Oh are you in for a treat, Celia! Road orders can be absolutely WONDERFUL resources! Have fun!

Thank you! Thank you! Judy, you’ve answered several niggling questions I hadn’t gotten around to researching yet:

>I’d found road orders in North Carolina in the county minute books for the Court of Pleas and Quarter sessions. But I’d always wondered how my third and fourth great grandfathers knew exactly how many miles they rode when they attended court as a witness for someone. Court minutes show they were reimbursed for amounts like 23 or 44 miles, and I knew these weren’t just random guesses. Duh! Mile markers.

>And now I know why Louisiana parishes had Policy Juries. Looks like I’m going to have to look into those Louisiana records.

It’s just too bad that my Mississippi kinfolk didn’t arrive in Tishomingo County until after 1852, because the transcribed records you found would have been a great help. But, it’s all good…I know a lot more than I did before reading your blog post.

I did the same “duh! mile markers!” thing, Kathy! And after 1868 in Tishomingo look at the Board of Supervisors records.

In the Pittsylvania Co VA court house, I learned the lesson; always look at all books/records. I was stumped and decided to look at all of the books which were old enough to have some info on my folks. I climbed up on a chair to reach the top of one stack and got down a book entitled “Accounts Current”. Now, what do you reckon was in it? Estate inventories!!!!! I’d have never guessed. So, after that, I developed the policy I still follow: look at everything no matter how unlikely a source it appears to be. You just never know what they chose to call the records you want.

You betcha, Jo! I came across a whole set of criminal court records in a book with a similar name in another Virginia county courthouse.