Corpus, not corpse

At 2:00 this afternoon, the Vermont Judicial Historical Society will put on a mock trial centering on the disappearance, 200 years ago, of one Russel Colvin of Manchester, Vermont.1

To all eyes, in those early days of the 19th century, it appeared to be a terrible crime, uncovered — as oddly as it might seem — by a dream.

Colvin lived with his wife Sally and two children in the home of his father-in-law Barnet (Barney) Boorn. Two of the Boorn sons — brothers Jesse and Stephen Boorn — lived there as well and were widely known to have disliked their brother-in-law, a man who seemed to do little but produce more children by their sister for them and their father to support.2

When Colvin disappeared in May of 1812, foul play was suspected. But there wasn’t any real evidence and no-one was charged. It wasn’t until Amos Boorn, an uncle of the brothers, dreamt that the missing man came to him, said he’d been murdered and described the place where he’d been buried that the authorities focused again on the brothers.

And when a dog digging near a stump on the family property uncovered some bones in April 1819, it seemed that a Divine Hand was leading the way to justice.3

Jesse Boorn was arrested. Even though the bones turned out not to be human bones, a button and a knife purportedly belonging to the missing Colvin were found and identified by various persons, including Colvin’s wife.4

Reports surfaced that Jesse pinned the murder on Stephen — then living in New York — reports fostered by a forger who was Jesse’s cellmate. In fact, the forger — Silas Merrill — agreed to testify against the Boorns if he was set free. The prosecutor struck the deal, Merrill was released, and a warrant was issued for Stephen’s arrest.5

There was some thought that Jesse may have named Stephen thinking Stephen was beyond the reach of Vermont law. But when the Vermont officers went to New York, Stephen agreed to come back saying he wanted to clear his name. At that point, Jesse recanted what he’d said about Stephen.6

But public pressure mounted and the brothers were indicted for capital murder in September 1819. Witnesses started to come forward saying the brothers had made comments about Colvin being dead. And Stephen didn’t help things when he said he had hit Colvin, but only in self-defense.7

The case went to trial in November, and the key pieces of evidence were the confessions each had made to a fight where Stephen had struck Colvin in the head with a hoe. Those confessions, offered in evidence over the objections of the defense lawyers, described where the body had been buried — even though not a single human bone was ever found. The jury wasted no time, deliberating less than an hour before finding the two men guilty. They were sentenced to be hanged for their crime.8

Defense counsel petitioned the Vermont Legislature for mercy. A special session of the General Assembly considered the case. Because he wasn’t the man who swung the hoe, Jesse’s sentence was commuted to life in prison by the Legislature. But Stephen’s petition was rejected.9

Stephen was scheduled to die on 28 January 1820. Justice, the community thought, would finally be done — brought about by Divine Intervention in the form of a dream.10

There was only one small problem.

The brother-in-law, Russell Colvin, wasn’t dead. To the contrary, he was alive and well — though perhaps not entirely compos mentis — and living on a farm in Monmouth County, New Jersey.

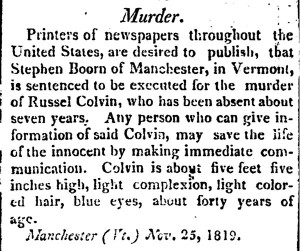

The only thing that intervened here was that Stephen had urged his counsel to ask newspapers across the country to print a notice asking for information about Colvin. The piece ran far and wide and read, in part:

Stephen Boorn of Manchester, in Vermont, is sentenced to be executed for the murder of Russel Colvin, who has been absent about seven years. Any person who can give information of said Colvin, may save the life of the innocent by making immediate communication.11

And a New Jersey man read the piece in a New York newspaper and wrote a letter to the editor and to the postmaster in Manchester. Nobody in Vermont cared much about the letter, but a former Manchester resident living in New York read it, went to New Jersey, and found Colvin. He tricked him into coming back to Vermont where, faced with the living proof that there had never been a murder, the court granted a motion for a new trial and the prosecutor dismissed the charges.12

Cool stuff for members of a lot of Vermont families, especially since all three of the key players — Russel Colvin, Stephen Boorn and Jesse Boorn — had children and both the Colvin and the Boorn families continued to live in the Manchester area13 (though Stephen and Jesse went west, to Ohio and Pennsylvania). Cool enough to warrant that mock trial this afternoon — not for murder, mind you, but by Stephen Boorn for damages against Vermont for false imprisonment.

That might be warranted since, according to the Vermont Judicial History Society,

Colvin’s reappearance sent shock waves through the legal community, and left the Vermont judiciary with a black eye, as commentators criticized the Vermont Supreme Court for allowing the conviction in spite of the lack of a dead body…14

Or, as some commentators put it, there was no corpus delicti. Vermont, they said, should have listened to English jurist Matthew Hale: “I would never convict any person of murder or manslaughter, unless the fact were proven to be done, or at least the body found dead.”15 So, they argued, there should never have been a murder conviction since the body wasn’t found.

Um… not so fast. That’s not what corpus delicti means. Though the corpse of a murdered man is an example of a corpus delicti, the term simply means the body of a crime: “the substance or foundation of a crime; the substantial fact that a crime has been committed.”16 Generally, the law doesn’t — and didn’t — require that a murder victim’s body be found. In 1858, for examnple, three sailors were convicted of killing their crewmates on a ship even though the ship and the crewmates’ bodies were never found. 17 Otherwise, as one 1834 court said, a clever killer who sucessfully disposed of the body could get away with murder and “a more complete encouragement and protection for the worst offences of this sort could not be invented, than a rule” that required that the body be found.18

What it does mean is that a confession by itself was and is usually not enough: there has to be some independent evidence beyond the words of a defendant that there actually was a murder. A few drops of blood, a bone fragment, some evidence of violence of some sort usually is enough.19 In fact, through April 2012, there had been 366 trial in the United States where no body was ever found and about 90% resulted in convictions that were upheld and 10% in acquittals or convictions that reversed or set aside — including the Boorn case,20

So when reading a murder case record, then, remember that it’s the corpus delicti, and not the corpse, that has to be there.

Unless, of course, a defendant has an uncle who dreams…

SOURCES

- “History Repeats Itself,” posted 10 Jul 2012, Supreme Court of Vermont Blog (http://scovlegal.blogspot.com : accessed 12 Jul 2012). ↩

- Lewis Cass Aldrich, History of Bennington County, Vermont (Syracuse, New York : D. Mason & Co., 1889), 365; digital images, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 12 Jul 2012). ↩

- Ibid., 365-366. See also “America’s First Wrongful Murder Conviction Case,” Center on Wrongful Convictions, Northwestern University Law School (http://www.law.northwestern.edu/wrongfulconvictions/ : accessed 12 Jul 2012). ↩

- Aldrich, History of Bennington County, Vermont, 366. See also Leonard Sargeant, The Trial, Confessions and Conviction of Jesse and Stephen Boorn for the Murder of Russell Colvin: And the Return of the Man Supposed to Have Been Murdered, (Manchester Vt: Journal Book & Job Office, 1873), 6-7; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 12 Jul 2012). ↩

- “America’s First Wrongful Murder Conviction Case,” Center on Wrongful Convictions. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Sargeant, The Trial, Confessions and Conviction of Jesse and Stephen Boorn…, 9-10. ↩

- Ibid., 10-11. ↩

- See e.g. The London (England) New Times, 3 January 1820, p. 4. ↩

- “Murder,” Bangor (Maine) Weekly Register, 16 December 1819, p. 3, col. 2. ↩

- “America’s First Wrongful Murder Conviction Case,” Center on Wrongful Convictions. ↩

- Aldrich, History of Bennington County, Vermont, 366. ↩

- “History Repeats Itself,” posted 10 Jul 2012, Supreme Court of Vermont Blog (http://scovlegal.blogspot.com : accessed 12 Jul 2012). ↩

- 2 Hale, Pleas of the Crown 290 (1678) (emphasis added). ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 280, “corpus delicti.” ↩

- United States v. Williams, 28 F. Cas. 636 (No. 16707) (C.C.D. Me. 1858). ↩

- United States v. Gibert, 25 F. Cas. 1287, 1290 (C.C. Mass. 1834). ↩

- See e.g. People v. Manson, 139 Cal. Rptr. 275, 298 (Cal. App. 1977). ↩

- Thomas A. DiBiase, ““No body” Murder Trials in the United States,” pdf file (www.nobodymurdercases.com : accessed 12 Jul 2012). ↩

What an interesting case! I am surprised no one has made a movie about it yet.

Nobody wanted to play the small, not-entirely-with-it brother-in-law…

In the mid-80’s a television movie called “Murder in Coweta County” was made starring Johnny Cash and Andy Griffith about the true story of a 1930’s murder in Coweta County, Ga. where a wealthy businessman by the name of Strickland killed someone who had worked for him and had the man’s body dumped in a well. Fearing the body would be found, he had it pulled out of the well and burned. For several years an investigator (the Johnny Cash role) worked very hard to prove that Mr. Strickland had committed the murder, but couldn’t actually prove a murder had been committed because the victim was simply “missing”, similar to the fascinating case Judy talks about. He was finally convicted because a small piece of human bone was found in a pile of ashes and, coupled with testimony from a reluctant witness, it was enough to convict him of murder. It was a fascinating book, so-so movie….but I immediately thought of it when reading this story.

That little bit of bone plus the testimony of the witness would absolutely be enough to establish the corpus delicti in most jurisdictions these days! The real problem with the confession cases is the sheer number of people who confess to crimes that never happened or to crimes they didn’t commit because they’re non compos mentis at the time…