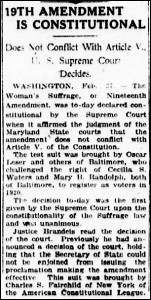

Court upholds 19th amendment

It wasn’t all that long ago, really — just a mere 91 years ago today — that the right of women to vote in the United States hung in the balance.

It began in Maryland with two women, one white and one black, who applied on 12 October 1920 to register to vote. Cecilia Street Waters and Mary D. Randolph, both citizens of Maryland and residents of the 11th ward of Baltimore City, sought to exercise their rights under the newly ratified 19th amendment to the United States Constitution.1

It began in Maryland with two women, one white and one black, who applied on 12 October 1920 to register to vote. Cecilia Street Waters and Mary D. Randolph, both citizens of Maryland and residents of the 11th ward of Baltimore City, sought to exercise their rights under the newly ratified 19th amendment to the United States Constitution.1

That amendment, you’ll recall, provided simply that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”2

But there were men in Maryland who didn’t want that to happen. That state’s Legislature had voted against ratification, and Oscar Leser, an attorney “on his own behalf, and on behalf of the Maryland League for State Defense,” challenged the registration of the women and filed suit claiming that the 19th amendment had never been legally ratified and that it couldn’t override provisions in various state Constitutions that limited the vote to men.3

Now there’s not a lot known about any of the players here.

There’s no white woman named Cecilia Street Waters who can be found in Baltimore’s 11th Ward in 1920 census, no articles online detailing her life, not one single family tree posted online claiming descent from or even collateral relation to her that The Legal Genealogist could find in a quick survey.

The 1920 census offers two candidates for the Mary Randolph of the case. One was a 34-year-old restaurant worker, a married woman but living with her brother.4 The other was a 25-year-old maid living with her husband, a stevedore on the docks, as lodgers in a rented house in the 11th ward.5 And, of course, she might not have been recorded on the census at all.

Did they know, either of them, that their names would be passed down through the years as the women whose simple act of registering to vote would prove so pivotal? Maybe, but probably not. We just don’t have enough information to make a guess as to whether they expected to be so bitterly fought.

Oscar Leser, however, was clearly the front man for this challenge. The census tells us that in 1920 he was 49 years old, born in Missouri of German-born parents, married with two children enumerated with him. He was shown as a boarder in the Albion Hotel in Baltimore. His occupation: lawyer in the state tax courts.6

Leser filed his suit on 30 October 1920, not even three weeks after the women sought to register to vote.7 The trial court ruled for the women and in favor of their right to register. Leser appealed, but on 28 June 1921, Maryland’s highest court, the Court of Appeals, upheld the lower court’s decision. It said there wasn’t any principled distinction between the 15th amendment (“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color or previous condition of servitude”) and the 19th amendment (which “but adds the word ‘sex’ … and thus brings another class of citizens within the reach of the prohibition against discrimination”).8

And Leser appealed again. That brought the case to and left the decision entirely in the hands of a group of men. Nine of them, to be exact. All members of the United States Supreme Court.

• Joseph McKenna of California. Born in Philadelphia in 1843. An attorney and District Attorney in California, he was elected to the California legislature and the U.S. House of Representatives. He was appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in 1892, to be Attorney General of the United States in 1897, and then to the Supreme Court in 1898.9

• Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. of Massachusetts. Born in Boston in 1841. A Civil War veteran, lawyer and professor at Harvard Law School, he was appointed to the Massachusetts Supreme Court in 1882 and served for 20 years, including three years as its Chief Justice. In 1902, he was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court.10

• William Rufus Day of Ohio. Born in Ravenna, Ohio, in 1849. An Ohio attorney who served in the U.S. State Department, he was appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in 1899, and then to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1903.11

• Willis Van Devanter of Wyoming. Born in 1859 in Marion, Indiana. A lawyer in private practice in the Wyoming Territory, he was the city attorney of Cheyenne and a territorial legislator before being named Chief Justice of the Wyoming Territorial Court in 1889. He was appointed Assistant U.S. Attorney General in 1897, to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit in 1903, and to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1910.12

• Mahlon Pitney of New Jersey. Born in Morristown, New Jersey, in 1858. An attorney in New Jersey, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and the N.J. State Senate before being appointed to the N.J. Supreme Court in 1901 and Chancellor of the Courts in 1908. He was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1912.13

• James Clark McReynolds of Tennessee. Born in Elkton, Kentucky, in 1852. A lawyer and an adjunct law professor at Vanderbilt University, he was named Assistant U.S. Attorney General in 1903 and U.S. Attorney General in 1913. He held that position only a year when he was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1914.14

• Louis D. Brandeis of Massachusetts. Born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1856. A lawyer and graduate of Harvard Law School, he was in private practice in Massachusetts who had built a reputation as “the people’s attorney” when he was named to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1916.15

• John H. Clarke of Ohio. Born in Lisbon, Ohio, in 1857. He had been in private practice as an attorney for 35 years when he was named as a judge of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio in 1914. He served there for two years and was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1916.16

• William Howard Taft of Connecticut. An Ohioan, really, born in Cincinnati in 1857. He’d been in private practice in Ohio and had been both an assistant prosecutor and a judge there before he was appointed U.S. Solicitor General in 1890. He was a judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit from 1892 to 1900, then Civilian Governor of the Philippines, U.S. Secretary of War, and President of the United States elected in 1908 for one term. He then taught at Yale Law School and was appointed Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court in 1921.17

Nine men. From the fiercely liberal Brandeis to the equally fiercely conservative Day. Not a woman in the bunch.

And 91 years ago today, those men issued their decision.

“Whether the Nineteenth Amendment has become part of the Federal Constitution is the question presented for decision,” wrote Justice Louis D. Brandeis, on behalf of the Court. And in four short paragraphs, he and the Court — unanimously — answered that it had. The Maryland decision was affirmed.18

Thank you, Cecilia Street Waters. Thank you, Mary D. Randolph.

And thank you to nine men, all born in the 19th century, who saw clearly what the 20th century required of them. For what their 21st century descendants enjoy.

SOURCES

Image: “19th Amendment is Constitutional,” The (New York) Evening World, 27 February 1922, p. 1, col. 5; digital images, “Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers,” Library of Congress, (http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/ : accessed 26 Feb 2013).

- Leser v. Board of Registry, 139 Md. 46, 52-53 (1921). ↩

- U.S. Constitution, Amendment 19, ratified 26 Aug 1920. ↩

- Leser v. Board of Registry, 139 Md. at 53-55. ↩

- 1920 U.S. census, Baltimore City, Maryland, 11th Ward, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 167, p. 150(B) (stamped), dwelling 81, family 116, Mary Randolph; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 26 Feb 2013); citing National Archive microfilm publication T625, roll 661. ↩

- 1920 U.S. census, Baltimore, Md., pop. sched., ED 168, p. 174(B) (stamped), dwell. 226, fam. 252, Mary Randolph. ↩

- 1920 U.S. census, Baltimore, Md., pop. sched., ED 166, p. 140(A) (stamped), dwell. 183, fam. 243, Oscar Leser. ↩

- “Attacks Validity of Suffrage Law,” The Washington (D.C.) Herald, 31 Oct 1920, p. 4, col. 2; digital images, “Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers,” Library of Congress, (http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/ : accessed 26 Feb 2013). ↩

- Leser v. Board of Registry, 139 Md. at 62. ↩

- “Joseph McKenna, 1898-1925,” The Supreme Court Historical Society (http://www.supremecourthistory.org/ : accessed 26 Feb 2013). ↩

- “Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.,” The Supreme Court Historical Society (http://www.supremecourthistory.org/ : accessed 26 Feb 2013). ↩

- “William R. Day, 1903-1922,” The Supreme Court Historical Society (http://www.supremecourthistory.org/ : accessed 26 Feb 2013). ↩

- “Willis Van Devanter, 1911-1937,” The Supreme Court Historical Society (http://www.supremecourthistory.org/ : accessed 26 Feb 2013). ↩

- “Mahlon Pitney, 1912-1922,” The Supreme Court Historical Society (http://www.supremecourthistory.org/ : accessed 26 Feb 2013). ↩

- “James Clark McReynolds, 1914-1941,” The Supreme Court Historical Society (http://www.supremecourthistory.org/ : accessed 26 Feb 2013). ↩

- “Louis D. Brandeis, 1916-1939,” The Supreme Court Historical Society (http://www.supremecourthistory.org/ : accessed 26 Feb 2013). ↩

- “John H. Clarke, 1916-1922,” The Supreme Court Historical Society (http://www.supremecourthistory.org/ : accessed 26 Feb 2013). ↩

- “William Howard Taft, 1921-1930,” The Supreme Court Historical Society (http://www.supremecourthistory.org/ : accessed 26 Feb 2013). ↩

- Leser v. Garnett, 258 U.S. 130, 135-137 (1922). ↩

Cecelia Waters is enumerated in the 11th ward in Baltimore in the 1900 and 1910 census. In 1900 Cecelia S Waters born June 1858 in Maryland is widowed and living with her stepmother Mary Ann Forbes on Howard Street. She is a dress maker. In 1910 she and her stepmother are lodgers living on W. Preston Street in Baltimore. Cecelia S Waters is an embroiderer working from home. Images accessed from Ancestry.com.

Thanks for that additional information, Beth! We can hope this is the right Cecilia Waters, but more research would have to be done to be sure.

Thank you for writing this.

Got to keep those memories alive, Anne! (Sure hope those related to these two women know their stories.)

Judy,

Love your blog. I love this blog post very much! A well written tale with law, history and genealogy interwoven marvelously.

I am a genealogist and my wife is finishing her law degree so this appeals to us both.

I love your blog so much, I added it to my blogroll. Please come visit my blog:

mikeeliasz.wordpress.com (aka Stanczyk – Internet Muse)

It is mostly about Polish Genealogy (written under my nom de guerre, STANCZYK, who an historical jester at the Polish court). From time to time, I delve into history or politics or culture (think WDYTYA).

Keep up your great work. I learned about your blog from an e-newsletter, Gen-Dobry.

–C. Michael Eliasz-Solomon

Wow, Michael, you’re so kind to say so! Good luck to you both — you on your blog (I’ll check it out!) and your wife on her law degree!