Paying the piper

You’ll find them in so many case files, tucked away in the courthouses and archives and online record collections of American lawsuits. Some are handwritten, some fill-in-the-blanks preprinted forms, some typewritten.

They can be confusing documents, but they can provide some wonderful leads.

They’re the bills of costs.

For example, on the 16th of November 1889, a woman named L. O. Hamilton sued her husband Jerome Hamilton for divorce in what is now Grays Harbor County, Washington.1 They were married, she said, in 1882, but by 1885 he’d taken off and “willfully and without cause deserted and abandoned the plaintiff and ever since has and still continued to willfully and without cause desert and abandon .. and to live separate and apart from her without any sufficient cause or any reason whatever.”2

For example, on the 16th of November 1889, a woman named L. O. Hamilton sued her husband Jerome Hamilton for divorce in what is now Grays Harbor County, Washington.1 They were married, she said, in 1882, but by 1885 he’d taken off and “willfully and without cause deserted and abandoned the plaintiff and ever since has and still continued to willfully and without cause desert and abandon .. and to live separate and apart from her without any sufficient cause or any reason whatever.”2

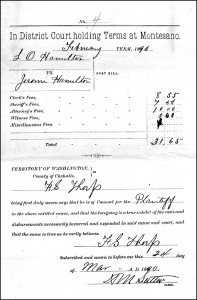

Jerome never bothered to answer the complaint, and the divorce was granted on the 17th of February 1890.3 And the very last document in the file is the one you see here, the cost bill… more typically called a bill of costs. (You can click on the document to see a larger version.)

This one is one of those fill-in-the-blanks forms, and it shows that the lawyer for the plaintiff swore there had been a total of $31.65 in costs and disbursements necessarily incurred and expended in prosecuting the divorce case: $8.55 in clerk’s fees; $7.50 in sheriff’s fees; $10 in attorney’s fees; $5.60 in witness fees; and $1 in miscellaneous fees.4

And why was he listing those costs?

Because, from the earliest days, costs were (and are) assessed against the loser in a lawsuit.

Costs, Black’s Law Dictionary says, are “a pecuniary allowance, made to the successful party, (and recoverable from the losing party,) for his expenses in prosecuting or defending a suit or a distinct proceeding within a suit.”5 And a bill of costs is simply “a certified, itemized statement of the amount of costs in an action or suit.”6 Sometimes costs were awarded in small bits and pieces, even during a lawsuit, but usually what you’ll see is a bill for the final costs, “such costs as are to be paid at the end of the suit; costs, the liability for which depends upon the final result of the litigation.”7

So the first thing you’ll find out when you see a bill of costs in a case file is who won — something that may not always be clear from the records that survive or from the language the court uses in a final order.

This bill of costs tells you there were pretty hefty fees for the clerk. These would be things like filing fees for the original complaint and for any additional documents that had to be filed. They’d also include copies of documents the clerk made for the parties, like an official copy of the divorce decree. Checking the fees against the documents in the file may tell you that there may be other records you need to look for, or at least that any surviving court docket may provide information about.

It also tells you that there were fees paid to the sheriff — usually the fees to serve the original complaint on the defendant and subpoenas for any witnesses who had to be called. It’s a clue that there may be records from the sheriff’s office itself, in the court file or elsewhere, to look at. Here, the sheriff actually filed a document setting out the fees for serving the defendant, and the total was the same as the amount shown in the bill of costs. And the two in combination give you a nice clue: the sheriff’s fee statement gave the round-trip mileage — 40 miles at 10 cents a mile. You now know that the defendant lived roughly 20 miles from the courthouse.

This bill of costs also tells you the court actually took testimony on this divorce case — one of the line items is for witness fees. Since the sheriff didn’t have to serve subpoenas, you know these were witnesses friendly to the plaintiff who came in without being subpoenaed. And while there’s no guarantee that the witness records still exist, at least now you’d know to go and look. You may at least get the witness’ names from the court docket.

What isn’t terribly common about this bill of costs is the line item for attorney’s fees. Generally in the United States we have what’s called the American Rule — every litigant pays his or her own lawyer.8 But there are exceptions to that rule, and one very common exception is in divorce cases.

This case file doesn’t say what happened to Mrs. Hamilton’s bill of costs — and that too is a clue that there may be more records out there as she, or her lawyer, tried to collect.

Bills of costs. Look for ’em whenever you find a court record.

SOURCES

- The county was originally Chehalis County. The name was changed to Grays Harbor in 1915. Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Grays Harbor County, Washington,” rev. 30 Mar 2013. ↩

- Chehalis (now Grays Harbor) County, Washington, Hamilton v. Hamilton, divorce case file no. 4; digital images, “Washington, County Divorce Records, 1852-1950,” FamilySearch.org (https://familysearch.org/ : accessed 14 Apr 2013); citing Washington State Regional Archives, SouthWest Region, Olympia, Washington. ↩

- Ibid., decree, Superior Court, Hamilton v. Hamilton, 17 Feb 1890. ↩

- Ibid., Costs Bill, 24 Mar 1890. ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 282, “costs.” ↩

- Ibid., 134, “bill of costs.” ↩

- Ibid., 493, “final costs.” ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “American rule (attorney’s fees),” rev. 25 Mar 2013. ↩

So, are you saying, Judy, that these are costs that the plaintiff paid that she will be trying to collect from her now-ex-husband? Is he the ‘loser’ in this case? I see that they are definite clues and can be important in putting together pieces, but I’m not sure I’m grasping the big picture.

Yup, he’s the loser because she won the divorce that she wanted. And yes, she would have had to pay the filing fees and sheriff’s fees and the like up front, and then get paid back (if she can track him down) by the ex-husband.

Thanks!

I love Virginia Chanceries (see VirginiaMemory.com) for getting all the records together on stuff like this. All the Witnesses records, the Bill of Costs, the initial complaint and response, witness subpoenas, newspaper clippings of notices in newspapers (and the cost listed in the Bill of Costs), Lots of them reference other related cases dealing with the same people…like a defendant starting a counter-suit against the plaintiff, or as you say, the lawyer trying to recoup costs for a suit. I found one on an uncle whose brother-in-law was suing him because he’d promised to sell the brother-in-law the family home, the brother-in-law moved in and made some improvements and then the uncle tried to sell the house to someone else. This was actually quite an important case to find since when the father died intestate a couple years before and his land was partitioned out by Chancery the uncle was not yet 21. But by the time of the house suit, he was…and someone wrote a date on the back of a letter and subtracted the year of the house suit and low and behold, the answer was 21! You think it might be the uncle’s birthdate? And other chanceries that went on for 30+ years, and constant notations that so-and-so died and these are her kids. With the final result that none of the original plaintiffs or defendants were still alive by the time the suit was settled 200 digitized images later! If you have Virginia ancestry…go take a look!

No question that Virginia’s chancery records are among the great treasures of genealogy! Thanks for reminding us all.