Not the same

Reader Tim Campbell is still puzzled by the issues raised in Maryland v. King, the U.S. Supreme Court decision last month that held that police are allowed to take a DNA sample from anyone arrested for a serious crime and that held, in essence, that a DNA sample isn’t a whole lot different from a fingerprint.

“We (who have had a DNA test) understand that DNA matching depends not only on the sample, but also the size of the database they have to compare the sample results to,” he writes.

“We (who have had a DNA test) understand that DNA matching depends not only on the sample, but also the size of the database they have to compare the sample results to,” he writes.

“So are we a step away from having Family Tree DNA being served with a warrant to turn over its database? If taking fingerprints and DNA samples is not a breach of Fourth Amendment protection from unreasonable search can the government demand our results for their law enforcement database? It is my understanding that police only need a 12-marker test result to identify an individual, so it seems that anyone having had a DNA test could be identified (I don’t know of any service that tests for less than 12 markers).”

Nope. Not a problem.

Because, first, there are all kinds of legal issues involved.

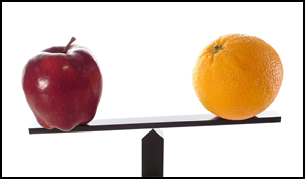

And because, second, we’re dealing seriously with apples and oranges here.

Let’s start with the most basic of basics when it comes to the legal issues.

The reason why the police might want a DNA sample is so they can use the results eventually in a prosecution. That, after all, was the focus of Maryland v. King — the use of DNA evidence taken when a man was arrested for one crime that then linked him to the commission of another crime.1

And to be able to use the results in a prosecution, the police have to be able to prove that the DNA results belong to you and not to, say, me.

That’s what underlies the requirement in Federal Rule of Evidence 901(a) that: “To satisfy the requirement of authenticating or identifying an item of evidence, the proponent must produce evidence sufficient to support a finding that the item is what the proponent claims it is.”2

And it underlies a concept called the chain of custody, a term that, “in legal contexts, refers to the chronological documentation or paper trail, showing the seizure, custody, control, transfer, analysis, and disposition of physical … evidence.”3

Now… I couldn’t tell you exactly when I produced the DNA sample I sent to Family Tree DNA. (Sometime in 2010, I know.) Or what post office I used to mail it in. (Home, maybe? Work?) I couldn’t tell you how it was handled between the time it left my hands and the time it arrived at the FTDNA lab. And, I dare say, the Postal Service couldn’t tell you either.

More importantly, other than my say-so, how would anyone know that the sample I sent in was mine and not that of one of my sisters or one of my female cousins?

Right there, we have what are fundamentally insurmountable problems with the chain of custody. That means, from a police perspective, the evidentiary value of the databases of the genetic genealogy companies is just about nil.

The simple fact is, as I’ve said before, “if the police have probable cause to believe that a crime has been committed and that you committed it, they can walk into any judge’s office in this country and get a search warrant that will let them pick you up, trot you down to the nearest medical facility, and take whatever blood or saliva they want for a DNA sample and they’ll use their own lab, not 23andMe or Family Tree DNA, to do the tests they want.”4

But there’s a much more important reason why the last place the police will turn for DNA is the data compiled by the genetic genealogy companies. That’s where the apples-and-oranges bit comes in.

The markers we test for in genetic genealogy aren’t the same markers the police test for in law enforcement.

As genealogists, we’re looking for genetic evidence of how we are like other people — other family members who share common ancestors with us. So genetic genealogy tests look to identify common factors that help us group people together: all those men who share certain YDNA markers, for example, that allow us to say with some confidence that they’re all descendants of some guy who lived back in 1700. Or all those women who have passed down certain mitochondrial DNA characteristics that allow us to say with some degree of confidence that their descendants living today all share a common female ancestor.

Those markers — those characteristics — aren’t really useful to the police at all. What they’re looking for, what is recorded in the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) system by the FBI (which is used by other countries like Canada5), are the parts of the DNA that make us unlike other people and set us apart as individuals.

As described by the Court in Maryland v. King:

The CODIS database is based on 13 loci … which … make possible extreme accuracy in matching individual samples, with a “random match probability of approximately 1 in 100 trillion (assuming unrelated individuals).” … The CODIS loci are from the non-protein coding junk regions of DNA, and “are not known to have any association with a genetic disease or any other genetic predisposition. Thus, the information in the database is only useful for human identity testing.”6

The CODIS markers aren’t included in the results recorded by genetic genealogy companies like Family Tree DNA, 23andMe or AncestryDNA. And the markers included in CODIS aren’t useful for genetic genealogy.

So adding the genetic genealogy databases to the law enforcement databases would literally be adding apples to oranges. With the predictable result of fruit salad, not evidence useful in court.

SOURCES

- Maryland v. King, No. 12-207, slip opinion (U.S. Supreme Court, 3 June 2013; PDF of opinion available at U.S. Supreme Court website (http://www.supremecourt.gov/ : accessed 3 June 2013). ↩

- Federal Rule of Evidence 901(a); html version, Legal Information Institute, Cornell University (http://www.law.cornell.edu : accessed 6 Jul 2013).. ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Chain of custody,” rev. 13 Mar 2013. ↩

- Judy G. Russell, “DNA and paranoia,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 11 Jan 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 6 Jul 2013). ↩

- See “Technology,” National DNA Data Bank, Royal Canadian Mounted Police (http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca : accessed 6 Jul 2013). ↩

- Maryland v. King, slip opinion at 6 (internal citations omitted). ↩

Thanks, Judy. The clarification helps.

Thanks for the question, Tim! Yours are always good ones! (I have at least one other in the queue, I think…)

The first I remember hearing about the kind of DNA testing that is now being used by genealogists was in connection with the attempt to reunite the children of Argentina’s “disappeared” with their grandparents. With their birth parents dead and no memory of anyone other than their adoptive family, this kind of DNA testing was the only way to prove the true identities of the lost children.

I did not realize that as many as 80% of the children were never found and have grown to adulthood without knowing that the people who raised them may have been complicit in killing their birth parents. Some who may suspect the truth, but do not want to confirm their fears, are now being forced by Argentine courts to undergo DNA testing against their wishes. To make matters worse for them, a positive DNA identification may subsequently result in criminal proceedings against the only mother and cather they have ever known.

There doesn’t seem to be any good solution to this. Which is worse: to lose your children and know your grandchildren are in the hands of people who have taught them to hate you, or to see the people you thought were your parents jailed for stealing you from strangers you’ve never met? At this point, no matter what is done, it seems like everyone involved is going to come out a loser. I can’t help wishing the Argentine legal system had taken serious action 20-30 years ago, when the lost children were still children who might have been better able to reintegrate with their birth families.

http://www.theworld.org/2010/11/argentina-dna-test-children/

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-12620384

There’s no question that this sort of thing is agonizing. I can’t imagine being put in that position: trying to choosing between knowing who I was… and knowing that the answer might send people I love to prison.

“The CODIS markers aren’t included in the results recorded by genetic genealogy companies like Family Tree DNA, 23andMe or AncestryDNA”

Well, okay – they are not in the results.

But — do those markers that CODIS is concerned with actually exist in the sample that we would provide and would be stored with these companies?

If they are — then the concern is still valid.

(a) They don’t exist usefully. The chain of custody issues alone dictate that conclusion, plus the logistical nightmares involved here.

(b) You don’t HAVE to have a sample stored with a DNA company, so if you have any concern about this, tell the testing company to destroy any remaining sample after the genetic genealogy tests are concluded.

(a) — I hope you are correct, but…

for the sake of argument (and paranoia)

With recent far reaching programs implemented by the NSA, it no longer seems like a stretch to consider this type of information 100% secure, does it? Or at least immune to a very general and vague warrant.

John, trust me on this one (and I speak as a former prosecutor): if government wants your DNA, it will get it. And it will get it much more easily, with far fewer hindrances, than going after a DNA company’s holdings. It will (perfectly legally) grab the trash you set out for collection and take things from it that might have your saliva. It will (perfectly legally) follow you to a restaurant and grab a pizza crust or glass you leave behind. It will (perfectly legally) get a warrant to haul you down to the local hospital for a blood sample. Getting it from a DNA company where it can’t be used as evidence because of chain of custody issues will be a LAST resort.

Judy, I don’t disagree at all with your analysis, but there could be another angle, too. Let’s hypothesize (I’ve read that lawyers love to hypothesize.):

The policeman takes samples of some unidentified thug from an evidence kit and there are no CODIS matches. He then mails them (assuming the policeman is not in Maryland or New York, of course) off to 23andme and FTDNA. Y-37 results show the perp is associated with a long line of Hickenloopers. He checks the phone book, finds a Hickenlooper in the neighborhood, gets a warrant, develops further evidence, and Hickenlooper winds up in jail. Good police work and a win for society.

But suppose there’s no clear cut result from 23andme or FTDNA at first, so he subpoenas the entire data base from both companies and finds a sibling match from a Hickenlooper’s autosome. (The Hickenlooper family are good genealogists, but did not make their data public or approve sharing requests.)

Same result in both cases – a win for society. In neither case was there a need for a chain of custody or admissable evidence. He just used the information for leads and then narrowed in on a suspect and perhaps then got a legallly obtained DNA sample for CODIS.

Cheers,

Bob Kirk

Too many supposes. First example, the copy is lying to FTDNA and 23andMe about his authority to submit the sample to either of those companies. That begins a chain of events that usually leads to exclusion of evidence at the end because of a doctrine called the fruit of the poisonous tree. Second example, DNA company fights the subpoena as overly broad and — sure bet here — wins.

(1) A policeman lies in the course of an investigation? Who woulda thought? Don’t the courts say that’s ok?

(2) Don’t companies ever lose those subpoena fights? Verizon, Google, “national security”, etc. He may tailor the subponea more narrowly – all who match… for instance.

I’m sure we could all imagine parades of horribles here… but there is a reason why we separate fact from fiction. It’s simply easier and cheaper with DNA for the cops to do it the right way.

http://apnews.myway.com/article/20130712/DA7FQUPG0.html

I came across this today. Thought it was an interesting read to add in to this discussion.

Oh! That’s very different! (to quote Rosanne Rosannadanna) And you make it clear. I think most of us have a good understanding of “chain of custody” just from TV cop shows. This is a kind of exciting decision — police won’t have to trick suspects into drinking a glass of water any more . . . .