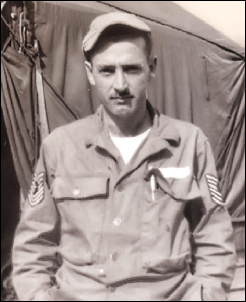

J.C. Barrett, 1920-1967

We all go through life with guilt as part and parcel of the baggage of being human.

Sometimes it’s a motivator. Sometimes it’s depressing. Sometimes it’s both.

And sometimes it can be the result of something that is a great comfort.

Such as the comfort I take from the fact that I grew up knowing my Uncle Barrett, who would have turned 93 years of age yesterday, the 12th of July.

Such as the comfort I take from the fact that I grew up knowing my Uncle Barrett, who would have turned 93 years of age yesterday, the 12th of July.

Which makes me always feel a little guilty — because his youngest children didn’t grow up knowing him. We lost Barrett to brain cancer when his sons were just young boys.

J.C. Barrett came into my family’s lives not long after World War II sent him to the Midland Army Air Force Base outside of Midland, Texas, and on the 12th of August 1942, he married my oldest aunt, Cladyne, in Odessa, Texas.

He was a career military man, eventually retiring from the Air Force as a master sergeant. And you can almost track his service career by the birthplaces of the children: my cousin Betsy in Texas, my cousin Kay in New Mexico, my cousin Barry in Texas, my cousin Tony in New York, and the baby, my cousin Steve, in Virginia.

Barry was only 12 years old when Barrett died. Tony was only seven. Steve wasn’t even five. And the brain tumor had affected Barrett greatly over the last years of his life. I don’t know how much of the man I knew and loved was really still there when his boys were old enough to have any real memories.

But the Barrett I knew was kind. He had a great heart. He was funny. The picture you see here is one of my favorites. It captures the impish humor perfectly.

But the Barrett I knew was kind. He had a great heart. He was funny. The picture you see here is one of my favorites. It captures the impish humor perfectly.

And I can’t ever think of him without three particular memories coming to the forefront every single time.

He rescued a kitten once, and probably saved my life (from the wrath of the other grown-ups). We were all my grandparents’ farm one summer, and I was sent out to pull up a bucket of water from the well.

If you were old enough to draw water, you were old enough to check to make sure none of the summer’s crop of kittens was around the well house. And I had checked. Thoroughly. What I hadn’t counted on was some brainless furball running up out of nowhere, literally climbing my pant leg and shirt and leaping from my shoulder into the well.

Now I realize people who rely on well water can’t leave a kitten clinging to the rocks at the bottom of a well. There wasn’t any choice but to rescue the kitten.

But the only one who didn’t blame me for days afterwards, the only one who said it wasn’t my fault, the only one who always had a kind word for me, was the one who got let down into the well, riding the bucket, to rescue the kitten. My Uncle Barrett.

Then there was the mudball incident. A bunch of us kids had been left at his and my aunt’s place one summer day while all the grown-ups were over at the farm, and one of his sons, one of my brothers and I decided to amuse ourselves by throwing mud balls as passing cars on the road.

I swear it had never occurred to me this was a bad idea. When Barrett drove up, I even asked him if he wanted to join us. Okay, so I was a slow learner.

Yeah, our ears were blistered… but he never told my father, who only came down on weekends. And my father would have killed me, for certain. So I’d have to say he saved my life at least twice.

But perhaps the best memory I have of my Uncle Barrett was another summer day when all of us kids were at his place and all of the grown-ups were at the farm. His house sat high on a hill, and a very serious storm was moving in fast. Several of us older cousins gathered up all the younger ones and we were huddling together in an inside room waiting for the storm to hit.

And just before it reached us, Barrett pulled up in his old station wagon. He took us all out onto the porch and, as the thunder boomed and the lightning flashed, he told us every story he knew — and some he probably made up on the spot — about storms. The thunder, he said, was the gods bowling. The lightning was when Thor, god of thunder, was hammering on his forge and kicked off a spark.

After just a few seconds, we weren’t scared of the storm any more. We were fascinated by the stories. And I don’t think there’s anyone alive today from those kids who were on that porch who’s ever been afraid of a thunderstorm again.

I am so very grateful that I knew my Uncle Barrett. And I will always feel a little guilty — and deeply sorrowful — that his youngest children didn’t.

I can only hope they draw some comfort from knowing what he meant to me.

Very nice Judy!

It is stories and memories like this that, if we are lucky and they are preserved and passed on, will grant us all a bit of immortality. I think your Uncle Barrett just gained some measure of immortality through your recollections and the gift of them to his children!

Thanks, John. It really pains me to think that so many people he would have adored — he would have worshipped his grandchildren! — never got to know him.

Thank you, Judy. I, too, was one of the countless cousins who were also to young to remember him. the only great story I know was of him being traded for a dresser drawer ~ not the entire dresser, just a drawer. What a great story, and tiny glimpse into time. I used to imagine that occurring at the Farm, but I realized as I got older that it could not have been, and so I wonder more and more about what it was like in Texas for our family. what was the house like? I have seen a picture or two of my mother on a porch with her darling “Kitty Gay'” and one of Mama Clay outside near what I imagine might have been a flower bed? And so, please, any time you’d like to share more stories, or some of the insanely funny bits of saved correspondence, never ever hesitate.

Thank you again. I love you.

~ Donna

The dresser drawer story was one I almost included here, Donna — my mother was part of that story — but I wanted to keep the focus on Barrett.

But I did write the dresser-drawer story into my mother’s eulogy (see post here): “One of my own (favorite stories) is how a man who might have become my father became my uncle because of a dresser drawer. Seems my mother was dating this serviceman, and she kind of liked him, but her older sister liked him a bit more. At that time, things were a bit crowded with 10 kids sharing quarters, and my mother — as the younger sister — had to keep all her things in boxes under the bed. My Aunt Cladyne — as the older sister — had the treasured dresser drawer. High level negotiations resulted in a swap. It’s because Mom got the dresser drawer that some of you out there are Barretts.”

I write about my family — usually the one you and I share, but sometimes on my father’s side — every Saturday.

Bollucks… I’ll never forgive my “smart phone” for constantly changing my spelling, or sometimes inserting words of its’ own creation. I was, of course, “too” young.

Oh well.

I think we all knew what you meant! 🙂

Beautiful stories, Judy. Thank you!

Thanks for the kind words!

Beautiful stories! These are the things future generations won’t ever be able to find while searching in vital, census, and court records, and I know you realize that. Being a family historian is just as vital as being a genealogist. Thank you for sharing these with more than just your family; they are priceless!

Thanks so much for the kind words, Miriam.

Judy, this is lovely the way you memorialize your family members. Thank you for being an inspiration to all of us.

Making sure to remember the people important to us in our own lives — and not just our ancestors! — is part and parcel of what we all need to do, Brenda!

Great memories for you. You made me wish I had known him. Love your stories!

Aw, thanks, Shelley. You sure would have liked him.

A wonderful portrait of Uncle Barrett. A man who understands kids is a kind and creative and flexible man. Three great anecdotes! Thank you. I believe I will always remember Barrett riding the bucket down into the well to rescue the kitten — after he let you know it wasn’t your fault. Simply lovely.

He even said it wasn’t my fault AFTERWARDS, which is even more remarkable!!