Noticing the law

The place was Lee County, in northwestern Illinois.

Formed in 1839 from Ogle County1 and named for Lighthorse Harry Lee of the Revolutionary War.2

Formed in 1839 from Ogle County1 and named for Lighthorse Harry Lee of the Revolutionary War.2

Population between 1910 and 1920, just about 28,000 people. And the county seat of Dixon was the boyhood home of President Ronald Reagan.3

So… here’s The Legal Genealogist‘s pop quiz for a Wednesday:

As of the summer of 1918, what were five of the most public places in the county?

What? Giving up so soon?

Well, all in Dixon, there was:

• Ben Barr’s feed shed.

• Roy Barron’s blacksmith shop.

• Charles Self’s blacksmith shop.

• The bulletin board on the corner of East and First Street.

• And the United Cigar Store.

And how in the world would we ever know that?

From court records, of course.

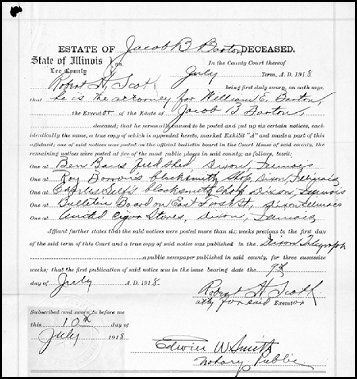

In particular, from the probate file of one Jacob B. Barton of Sublette, Lee County, who died in 1912, and whose estate was being finally settled in the summer of 1918.4

It’s an interesting probate file for other reasons — Jacob was the first druggist in Sublette and compounded medicinal remedies that were widely sold for a variety of ailments5 — but it’s this list of places that offers a clue we can use even if we’re not part of the Barton family but merely have ancestors from Illinois.

It’s an interesting probate file for other reasons — Jacob was the first druggist in Sublette and compounded medicinal remedies that were widely sold for a variety of ailments5 — but it’s this list of places that offers a clue we can use even if we’re not part of the Barton family but merely have ancestors from Illinois.

You see, the list was set out on a preprinted form that required someone — in this case, the attorney for the executor — to tell the court that he’d “personally caused to be posted and put up six certain notices … one of said notices was posted on the official bulletin board in the Court House …, (and) the remaining notices were posted at five of the most public places in Lee County.”6

And when you’re seeing that kind of language on a preprinted form, you can pretty well bet that this was a requirement in the law.

The law in Illinois, when Jacob Barton died and his estate was being settled, had a requirement that every administrator or executor of an estate had to give notice to creditors to present their claims. It had to be published “for three successive weeks in some public newspaper published in the county, or if no newspaper is published in the county, then in the nearest newspaper in this state, and also by putting up a written or printed notice on the door of the court house, and in five other of the most public places in the county.”7

And that had been the law in Illinois for decades before: the requirement appears, almost word for word, in the 1845 statutes as well.8

Okay… and just what do we do with that little bit of information?

Think about it for a minute:

If I’m telling the story of my ancestors, I always want to think about the things they might have done every day or every week or every month. I want to think about the places where they might have gone.

I want to know as much as I can about the patterns of life in the community where they lived. What people could have been expected to do and where they could have been expected to be at the time and in the place where my people lived.

If they were male and of an age to serve in the militia, I want to know where the militia mustered and when. If they were farmers, I want to know about the local feed store. If they raised beef stock, I want to know about the local slaughterhouse.

I want to know about the stores and shops where they got their supplies. Places where — if I get lucky — I might find records of the things they bought or the times when they were extended credit.

Here, Illinois law gives me a big leg up. The probate files in every Illinois county starting at least as early as 1845 are going to tell me about “five … of the most public places in the county” where the people of that place and time believed that people would go, where they’d gather, and where they’d be most likely read the notices the law required to be posted.

They’re going to tell me where I can start to look.

So when we’re trying to find the stories of our ancestors and we’re thinking about the things they might have done… and the places they might have gone… we need to make sure we’re noticing the law. And what it tells us about things like the most public places in a county — the places everybody figured would be where folks — like our folks — would be.

SOURCES

- “Lee County History,” Lee, County, IL, website (http://www.leecountyil.com/ : accessed 17 Dec 2013). ↩

- Frank E. Stevens, History of Lee County, Illinois (Chicago : S.J. Clarke Publ. Co., 1914), 60; digital images, Internet Archive (http://www.archive.org : accessed 17 Dec 2013). ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Lee County, Illinois,” rev. 30 Aug 2013. ↩

- Affidavit of Publication and Posting Notice to Creditors, Estate of Jacob B. Barton, 8 July 1918, Probate case files box 217, Lee County Circuit Court Clerk’s Office, Dixon; digital images, “Illinois, Lee County Records, 1830-1954,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 17 Dec 2013). ↩

- Sublette, Illinois, Our Bit of U.S.A. : Sublette Centennial, August 17-18, 1957 (n.p., n.d.), 15; digital images, Internet Archive (http://www.archive.org : accessed 17 Dec 2013). ↩

- Affidavit of Publication and Posting Notice to Creditors, Estate of Jacob B. Barton, 8 July 1918. ↩

- §60, Chapter 3, Administration of Estates, in The Revised Statutes of the State of Illinois, 1912 (Chicago : Chicago Legal News Co., 1912), 20; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 17 Dec 2013) (emphasis added). ↩

- §95, Chapter 109, Wills, in The Revised Statutes of the State of Illinois, … 1844-‘5 (Springfield, Ill. : Walters & Weber, public printers, 1845), 552; digital images, Internet Archive (http://www.archive.org : accessed 17 Dec 2013). ↩

Again, way cool information.

Thanks for the kind words, Donna!

Yup, thinking outside the box again. No wonder I love to read your posts!

Awww… that’s so nice of you to say! Thanks!