Forced removals to America

Reader Nonna Good came across a reference and just couldn’t believe it. So she asked for clarification.

“Could a child aged 6 be sent as an unaccompanied child in bondage in the 1700s from England?” she asked. “And that’s exactly what it says — a child without an adult who is bound out?”

“Could a child aged 6 be sent as an unaccompanied child in bondage in the 1700s from England?” she asked. “And that’s exactly what it says — a child without an adult who is bound out?”

It may be hard to imagine in modern times, but the answer, simply, is yes.

In fact, many thousands of children were taken from England to the American colonies, as convicted criminals, as indentured servants and, all too often, without any legal process in England — kidnapped off the streets and sent off as merchandise to be sold as servants in the New World.

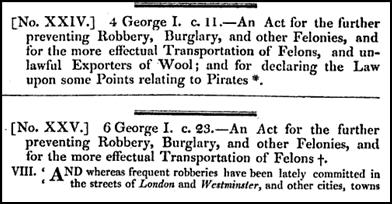

We start with the fact that, in 1718, an English statute institutionalized the concept of transporting someone to the colonies as an alternative to jailing that person for crime. Under that statute:

Transportation quickly became the preferred form of punishment for lesser felonies. At the Old Bailey session on April 23, 1718–the one immediately following passage of the Transportation Act–27 of the 51 people convicted of crimes were sentenced to transportation. They would be the first of the roughly 50,000 who were transported to America under the Transportation Act and who together represented a quarter of all British emigrants to this country during the eighteenth century. Transportation no longer involved simply banishing a criminal offender from England’s borders: it now became an institutionalized practice of emptying jails and forcibly ridding the country of undesirable elements, and the way it was carried out made it a unique American phenomenon.1

Because, under the law, children as young as eight years old could be convicted of crimes,2 children that young could be and were sentenced to transportation, bound out at one end of the voyage or the other to serve as indentured servants until they were adults.

In 1720, the law even made transportation more likely by authorizing payments to merchants who handled the transportations.3 Though the American Revolution forced a halt to transportation from England, before it ended, “approximately 52,200 convicts sailed for the colonies, more than 20,000 of them to Virginia. … An investigation of the skills held by one shipload of convicts revealed that of ninety-eight felons, forty-eight possessed no recognizable trade: sixteen of them were too young to have learned a trade”4 — in other words, children.

These convicts weren’t the only children brought to America. Children were sent off to the colonies indentured as servants by parents or guardians — and some were sent off simply by being swept up off the streets. Looking at colonial laws, we can see that Virginia legislated for indentures of children under the age of 12 as early as 1642-43.5

And children arriving without indentures — contracts that fixed time limits for servitude — could face much longer terms of service. Many of those children were simply kidnapped off the streets in England, Ireland and Scotland.6

To learn more about these transported children — with and without legal process — there are two really good books (among others):

• Peter Wilson Coldham, Emigrants in Chains: A Social History of Forced Emigration to the Americas of Felons, Destitute Children, Political and Religious Non-conformists, Vagabonds, Beggars and Other Undesirables, 1607-1776. (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Pub. Co., 1992); and

• Richard Hayes Phillips, Ph.D., Without Indentures: Index to White Slave Children in Colonial Court Records (Maryland and Virginia). (Baltimore, Md. : Genealogical Publ. Co., 2013).

Not a pretty part of our national history, is it? But one we need to kbow.

SOURCES

- See generally “The Need for a New Punishment: The Transportation Act of 1718,” Early American Crime (http://www.earlyamericancrime.com : accessed 20 Feb 2014). ↩

- Edward Christian, editor, Blackstone’s Commentaries on The Laws of England, Book I: Of the Rights of Persons (Portland : Thomas B. Wait & Co., 1807), 4653-464; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com/ : accessed 20 Feb 2014). Note that the pagination cited is drawn from the original. ↩

- “Punishments at the Old Bailey: Transportation,” The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, 1674-1913 (http://www.oldbaileyonline.org : accessed 20 Feb 2014). ↩

- Emily Jones Salmon, “Convict Labor During the Colonial Period,” Encyclopedia of Virginia (http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org : accessed 20 Feb 2014). ↩

- Brendan Wolfe and Martha McCartney, “Indentured Servants in Colonial Virginia,” Encyclopedia of Virginia (http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org : accessed 20 Feb 2014). ↩

- See Richard Hayes Phillips, Ph.D., Without Indentures: Index to White Slave Children in Colonial Court Records (Maryland and Virginia). (Baltimore, Md. : Genealogical Publ. Co., 2013). ↩

I just finished reading “White Cargo” by Don Jordan and Michael Walsh, and right from the beginning I couldn’t put it down. I recommend this to anyone who wants to pursue the subject.

Thanks for the recommendation, Shirley!

…And the British expected these transported folks to be ‘loyal’ to the British crown??? Hence the Revolutionary War – should have been no surprise to the British!!

So many of the British policies were almost guaranteed to have the colonists up in arms. Makes you wonder how they could have expected anything different, doesn’t it?

Thanks for writing about this topic, about which most are unaware. Interesting to think about the impact on the nation and on the lives of those who survived their indenture periods – and the rate of death amongst indentured servants was fairly high, according to an article I recently read.

Street urchins such as Dickens wrote about in “Oliver Twist” may have actually benefited from being transported, by serving their indenture time and then having the opportunity to succeed in a fledgling country where class and early history were not as important as in England. Many people made new lives for themselves by moving into the frontier, something that would not have been possible in England.

But it makes me wonder how many parents/families lost beloved children who may have been playing in the streets or running errands, and how frightening for the children who were kidnapped.

In October, I read the review by Bobbi King linked below about one of your referenced sources, Richard Hayes Phillips, Ph.D., Without Indentures: Index to White Slave Children in Colonial Court Records (Maryland and Virginia), which describes the scandalous slavery ring with ship’s captains stealing children off the streets and sending them to Virginia, where judges ruled on their futures and became their owners.

“Indentures were contracts of servitude between a purchaser of ship’s passage for an immigrant who worked off the price with years of unpaid work duty, earning only freedom after a certain number of years. Children who arrived by ship into colonial ports alone and without indentures were brought into the courts and sentenced to years of bondage duty.

Dr. Phillips has compiled an index of over 5000 names of children collected from the Court Order Books of colonial Maryland and Virginia. These county courts, with their panels of appointed judges called “Worshippfull Commissioners” in Maryland and “Gentleman Justices” in Virginia, left behind alphabetized names of thousands of children without indentures, lists of the names of the judges who sentenced the children into slavery, and the lists of the ships upon which the children were transported along with the names of the captains who commanded the vessels. A significant percentage of Worshippfull Commissioners and Gentleman Justices assumed ownership of the children they sentenced into servitude.”

http://blog.eogn.com/eastmans_online_genealogy/2013/10/book-review-without-indentures-index-to-white-slave-children-in-colonial-court-records-maryland-and-.html

Dick Eastman’s blog and Bobbi King’s book reviews there are top of my list of must-read resources. It’s where I heard of the Phillips book for the first time.

Yes, my 6th great-grandfather was just one of these non-indentured servants. With the book by Philips I finally learned of what happened to my grandfather and how and why he was brought here. And then with his newer release in 2015 I was able to find out where he was baptised and his parents names.

And how do we find these children if they are our ancestors? Perhaps this is where mine are.

English court records. English ship manifests. American passenger arrival lists. American court records and indentures. The Phillips book cited in the post for those coming into Virginia and Maryland. Unfortunat ely, there’s no one source.

Just read this posting after examining the ship’s lists for the ship Two Sisters that arrived in the port of Philadelphia in 1738 with a shipload of mostly Germans. It is one of the few surviving lists that names women and children in addition to men. Based on surname, a large percentage of the children appear to have no affiliation with the adults on board. Some are as young as 6. Most of what I have read about indentures, whether involuntary or to pay passage, have only discussed English speaking countries as participating in this practice. Is that what I am seeing on this ship’s list – unaccompanied minors who are indentured or something else like a really bad passage in which both parents have died?

There absolutely were Germans who paid their passage to the New World by promises of labor (what the English would call indentures). Whether these children were part of that system is something you’d need to examine in more detail.