Ask first

So last week the question posed to The Legal Genealogist was whether the cousin who had paid for a DNA test should share the results with the cousin who took the DNA test.

The no-brainer answer is yes.1 Just because you paid for a test doesn’t mean you can close off the results to the cousin whose DNA was tested.

The no-brainer answer is yes.1 Just because you paid for a test doesn’t mean you can close off the results to the cousin whose DNA was tested.

As noted last week, we now have working standards for genetic genealogists to consult when it comes to ethical questions like this. 2 And the applicable ethical standard here is that “Genealogists believe that testers have an inalienable right to their own DNA test results and raw data, even if someone other than the tester purchased the DNA test.”3

This week the question that came in was about the flip side of this issue: whether the cousin who paid for the test should share the results far and wide — with the name of the tested cousin, usually, still attached.

That answer should also be a no-brainer.

Unless you have consent, the answer is no.

No, no, no.

And in case that isn’t clear enough:

No.

The ethical standards are as clear on this as they were on the first question: “Genealogists respect all limitations on reviewing and sharing DNA test results imposed at the request of the tester. For example, genealogists do not share or otherwise reveal DNA test results (beyond the tools offered by the testing company) or other personal information (name, address, or email) without the written or oral consent of the tester.”4

Even when it comes to writing about DNA results for scholarly research, the standards require that:

When lecturing or writing about genetic genealogy, genealogists respect the privacy of others. Genealogists privatize or redact the names of living genetic matches from presentations unless the genetic matches have given prior permission or made their results publicly available. Genealogists share DNA test results of living individuals in a work of scholarship only if the tester has given permission or has previously made those results publicly available.5

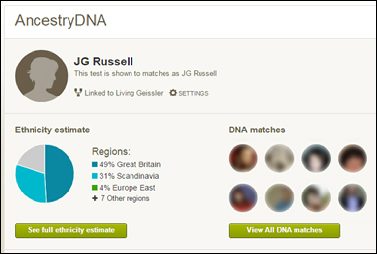

What this means, put in simple terms, is that we should not take a screen capture of DNA results from a testing company and post it in a blog post or on Facebook with the names or pictures of our matches still attached unless we’ve asked those matches specifically if we can post it.

And this isn’t a new idea, springing out of genetic genealogy alone. This is the long-time ethical standard of the genealogical community. This concept of protecting the privacy of living people can be found for example in:

• The Code of Ethics of the Board for Certification of Genealogists, which requires that board-certified genealogists pledge that: “I will keep confidential any personal or genealogical information given to me, unless I receive written consent to the contrary.”6

• The Standards for Sharing Information with Others of the National Genealogical Society, which advises us to “respect the restrictions on sharing information that arise from the rights of another … as a living private person; … inform people who have provided information about their families as to the ways it may be used, observing any conditions they impose and respecting any reservations they may express regarding the use of particular items… (and) require some evidence of consent before assuming that living people are agreeable to further sharing of information about themselves.”7

• The Code of Ethics of the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies, which notes that “If data is acquired that seems to contain the potential for harming the interests of other people, great caution should be applied to the treatment of any such data and wide consultation may be appropriate as to how such data is used. … Generally, a request from an individual that certain information about themselves or close relatives be kept private should be respected.”8

So as responsible genetic genealogists we don’t just take a screen shot and post it. We take a second, using the tools in every photo program out there — including my favorite free program Irfanview — and blur out the names or photos of our matches as you can see in the image above of my own AncestryDNA results.

Or we do something really unusual.

We ask first.

SOURCES

- Judy G. Russell, “Whose DNA it is anyway?,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 18 Jan 2015 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 24 Jan 2015). ↩

- See ibid., “DNA: good news, bad news,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 11 Jan 2015. ↩

- Paragraph 3, Standards for Obtaining, Using, and Sharing Genetic Genealogy Test Results, “Genetic Genealogy Standards,” GeneticGenealogyStandards.com (http://www.geneticgenealogystandards.com/ : accessed 18 Jan 2015). ↩

- Ibid., paragraph 8. ↩

- Ibid., paragraph 9. ↩

- “Code of Ethics and Conduct,” Board for Certification of Genealogists (http://bcgcertification.org/ : accessed 24 Jan 2015). ↩

- Standards for Sharing Information with Others, 2000, PDF, National Genealogical Society (http://www.ngsgenealogy.org/ : accessed 24 Jan 2015). ↩

- “IAJGS Ethics for Jewish Genealogists,” International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies (http://www.iajgs.org/ : accessed 24 Jan 2015). ↩

I wonder about the effect that HIAPA will have if applied to DNA testing for genealogy purposes?

Is it no longer considered a “medical” test in this context?

http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/privacyrule/

A genetic genealogy test by definition is not a medical test.

That’s why 23andMe can continue to provide the ancestry information even while it and the ZFDA are working out the issues over the medical information.

How would you categorize GEDMatch IDs (or other indirect bits of information), which can lead to the name of a person without too much effort?

I’d have to think about that, Ann. The fact is, GEDMatch isn’t a private pay-for-testing service and folks who upload their data there are necessarily running some privacy risks.

I’ve been thinking about this for a few days because I’m planning to do a post on DNA Circles with information from GEDmatch.

I humbly submit some suggested guidelines…

1. Don’t share so much information that you run a risk of making people regret having transferred their results to GEDmatch.

2. Don’t share so much information that you run the risk of getting GEDmatch into trouble.

3. If someone transferred their results to GEDmatch at your behest, be doubly considerate and careful about sharing results.

4. When in doubt, err on the side of caution. I would leave my audience confused and incredulous before I would upset someone by sharing too much information.

And perhaps, simply, don’t share identifying information — at all.

I have a similar question to Ann Turner’s. The clause “or made their results publicly available” seems to suggest to me that folks who have chosen to participate in Y-DNA surname studies on FTDNA (where the tester is identified only by their FTDNA kit number) or on ysearch.org (where the tester is identified by a new random five-letter tester code) have implicitly given their consent. Clearly we should not reveal “TGY1N is John Smith of Anytown USA” but would we be on the wrong side of the line to use these results without explicit permission from each tester?

The issue is, given their consent to what, Skip? The terms of each surname project can be different, and that’s what should control.

Ok. That’s a valid point. Let me ask it this way: What does the clause “or made their results publicly available” mean to YOU?

I’d say it’s a tad ambiguous, Skip, because it can be read as “name and kit number and actual results” or “kit number and actual results” or “name and kit number only” or …

When I checked out my recent photo hints on Ancestry last year, I saw that my great grandmother had one. It turns out that some other tester who saw the “shaky leaf” in the DNA matches screencapped the relationship image and uploaded that as the photo of my great grandmother. Nothing was blurred or covered.

I can’t really give a logical explanation for why I was so annoyed by it, but it was enough to make me debate taking my tree private for a while. I don’t mind people using those relationship guides to build out their own trees since it can really help with finding other researchers and matches to have those cousin lines, but using that screenshot as the only image just really annoyed me. I actually have plenty of lovely photos of my great grandmother that are public and could be saved to their tree when she was added.

I’d be annoyed, too, since part of the purpose of doing the test and being on Ancestry in the first place is to have the cousin contact us and work with us to advance our common understanding of our common heritage. When someone just gloms information, and limited information to boot, it doesn’t help either of us.

I do not believe that it is a cut and dry issue. Here’s a scenario that isn’t a real privacy issue: a screenshot is posted in a public forum with only names, no addresses or identifying characteristics whatsoever. It could be anyone in the world named Jane Doe and Ron Smith. No personal genetic information is shared. I do not see that as being an abrogation of an ethical code.

However, if their raw data or any personal identifying information is released without consent, then I would think that this is a big no no.

The problem is, there are only so many real people named Jane Doe or Ron Smith, fewer still who are involved with genetic genealogy and far fewer still who might possibly match me. Nope, sorry, this is Not A Good Thing. Don’t do it.

I respectfully disagree, but understand your point.

We teach law students that the phrase “I respectfully disagree” (or the more common, “with all due respect, your Honor”) really means “I think you’re full of it” — and that’s okay! 🙂 We need the debate to ensure everyone understands the issues.

Judy,

That wasn’t my intent at all! 🙂 In fact, I agree with most of the content of your article. I believe that in certain instances one could raise a “moral” objection as opposed to an “ethical” one.

It would be far easier for someone to breech privacy issues by linking a name on Facebook into a conversation if they are not a Facebook “friend”. In fact, there are too many privacy issues in public fora such as FB that many people are not aware of.I am very concerned about privacy issues for sure. On the other hand though, in areas where no positive identification can be made, and a private life cannot impacted in any way, then I can see where it would become a “no harm, no foul” issue. Even if one published a match bearing the name “Leonid Brezhniv” (and yes, I had to look up the spelling!)it does not positively identify it as THE Leonid Brezhnev.Ergo, it remains just a name, as opposed to a person.

I am truly constructing this as a strawman, but it is a point of view to consider. Realistically, if the client of a professional genealogist spotted his/her name as a result of the professional relationship, then the genealogist would find a real “ethical”issue to deal with.

I always appreciate your contributions to the community…

There are a lot of potential “no harm no foul” situations. The real concern is, we can’t know in advance which ones are in that category — and which ones are not. So since we’re dealing with living people, the default has to be to protect privacy. That was, we minimize the risk of fall out from our mistakes. And I agree these are moral or ethical issues (they’re synonymous really) and not legal issues.

*Leonid Brezhnev (great editing skills of mine.)

to add:*breach (I’m preoccupied with this blizzard that is going to swallow us)

(You and me both. I’m in the minimum 22″ and up to 30″ locally zone…)

Let me ask a two-part question.

I wrote a blog using a false name for someone who tested for me, because I knew some of his family had extreme issues of privacy. I did not ask him first, but he did not object. Was I required to ask first?

Now I am planning something more significant on the same story and asked him how he wants to be named. His response was that he wants to read it first. This implies giving him a veto, which I don’t want to give him. I can side-step him because his half-sister tested and she will give permission to use her real name, but he is my fourth cousin and I certainly don’t want to ruin our newfound cousinhood.

What does The Legal Genealogist think of all this? (I know that not everything has an answer in the law.)

You’re right, this isn’t a legal question but it is an ethical question. Why would you not allow him to read the portions you are writing about him, to let him give his input to those portions?

It’s not about him. It’s about his great-grandfather. he played a role in discovering one document and in his DNA, but the story is how I worked with that DNA and drew my conclusions.

To the extent that you rely on his DNA or his information, then you might consider that you owe it to him to consult (but no, I wouldn’t give him the right to censor).

I would like to see about getting my DNA tested to find out about my native American heritage. I have Cherokee and black foot on my father’s side, my grandparents.

Is there any way u can contact me so I can research my native American history?

Anything to help me get the answers I’ve been looking for.

Thank you

Charles Glover ll

If your Native American ancestry is that recent, it should show up in any of the autosomal DNA tests — AncestryDNA, Family Finder from Family Tree DNA or the test at 23andMe.

Judy,

I want to let you know that your blog post is listed in today’s Fab Finds post at http://janasgenealogyandfamilyhistory.blogspot.com/2015/01/follow-friday-fab-finds-for-january-30.html

Have a great weekend!

Thanks so much, Jana!