WDYTYA, the Battle of Trenton and lineage societies

Most of the time, when I watch Who Do You Think You Are, the power of the emotional hits the celebrities take at times during their discoveries comes as no surprise to me. One of the things that hooked me, completely, on genealogy back when I first started was how very much every single discovery of what my family lived through has made history come alive for me.

So I was feeling kind of sorry for Rob Lowe as I watched this past Friday night. He wanted so very badly to be descended from a genuine American hero — a Revolutionary War soldier — and it must have come as something of a shock when it became clear his ancestor John Christopher East was really a Hessian soldier Johann Christoph Oeste.

Anybody who goes from supporting Michael Dukakis to appearing on Hannity isn’t going to feel warm and fuzzy about that.

And then the program disclosed that Oeste had been at the Battle of Trenton. A Hessian soldier in uniform under arms at the Battle of Trenton. That’s a battle I happen to know a lot about… and to have had a very personal stake in.

And that’s what gave me my shock of the evening: an absolute gut-level visceral reaction I never would have expected. Logic went out the window, and pure emotion took over.

It wasn’t that I didn’t know much about Lowe’s Hessian ancestor and his comrades. It’s that I felt like I knew too much.

Because, you see, in the thick of that battle on the other side — the American side — was the 3rd Virginia Regiment of the Continental Line.

First authorized in December 1775, the 3rd Virginia Regiment of Foot began actively recruiting to fill its 10 companies in February 1776. The 4th Company of the Regiment was headed by Captain John Thornton and raised in Culpeper County on 12 February 1776. Among those who enlisted in the company were James Monroe, future President of the United States, and John Marshall, future Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, as lieutenants.1

And serving in the 3rd Virginia, in the very same company with Monroe and Marshall under Captain Thornton, were two brothers from Culpeper County, Virginia. The older, David Baker, was my fourth great grandfather. He signed up the day the company was formed and served as corporal throughout his two-year enlistment from 1776 to 1778.2

The younger was Richard Baker. My fourth great granduncle and, because of cousins marrying cousins, a first cousin many times removed.

The conditions the brothers faced in the assault on Trenton were appalling. One of Washington’s aides, believed to have been Col. John Fitzgerald, recorded:

It is fearfully cold and raw and a snowstorm setting in. The wind is northeast and beats in the faces of the men. It will be a terrible night for the soldiers who have no shoes. Some of them have tied old rags around their feet; others are barefoot, but I have not heard a man complain. They are ready to suffer any hardship and die rather than give up their liberty.3

These were the American patriots that Lowe’s ancestor and his Hessian comrades were trying to kill. They weren’t just trying to kill George Washington. They were trying to kill members of my family.

And, my family’s history records, Richard Baker, who was born 23 December 1753 in Culpeper County, Virginia, died 26 December 1776.4 At the Battle of Trenton. He was just three days past his 23rd birthday when he was killed. By the Hessians. At Trenton.

There aren’t any details of Richard’s death. Just a poignant and quiet statement by his brother David many years later when David applied for a pension:

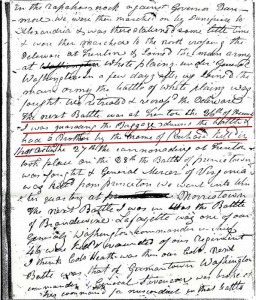

In a few days after we joined the main army the battle of White Plains was fought. We retreated & recrossed the Deleware The next Battle was at Trenton the 26th of Decemb – I was guarding the Baggage during the battle & had a Brother by the name of Richard killd in that action.5

Little is known or written about casualties among enlisted men at Trenton. David McCullough in his masterful 1776 could document no American troops killed in the fighting, but noted two froze to death in the terrible winter conditions.6 But David Baker’s use of the phrase “killd in that action” rather than saying “he died” to describe his brother’s fate suggests a death in combat, and at least one relatively contemporary account records:

Our loss is only two killed and three wounded. Two of the latter are Captain (William) Washington and Lieutenant (James) Monroe, who rushed forward very bravely to seize the cannon.7

Washington and Monroe were both officers in the 3rd Virginia. Monroe was a lieutenant in the Baker brothers’ own company. If the officers were rushing forward, it stands to reason the enlisted men were too, and a biography of Monroe says they were.8

We’ll never know for sure if that’s how and when Richard fell, but it well may be.

So I sat there listening to and watching the WDYTYA episode, getting more and more upset. It’s one thing to have history coming alive in your family history; it’s something altogether different to have the dead hand of your own family history playing out on the tube while somebody else is trying hard to justify his ancestor’s role in your family member’s death.

I couldn’t help but think of David. He was a young man, not yet 30, who had just lost his little brother. He must have been grief-stricken and guilt-wracked. He was the older brother who couldn’t save the younger. But his concerns were so much bigger than the Hessians’ “humiliation” of being marched through Philadelphia.

He and the rest of the 3rd Virginia didn’t get a rest in the Newtown Church the way the Hessians did. He had to keep on after that battle:

The 27th the cannonading at Trenton took place on the 28th the Battle of princetown was fought & General Mercer of Virginia was killd from princeton we went into Winter quarters at

princetownMorristown The next Battle I was in was the Battle of Brandewine. Lafayette was one of our Generals Washington commander in chief. 46 were killd & wounded of our regiment. I think Colo Heath was then our Colo. Next Batle was that of Germantown Washington commander & General Stevenson was broke of his command for misconduct in that battle I was then marched to Valey forge & there stationd untill I was discharged in february 1778 by General Woodford.9

Two years of service. Marching in the snow with bare and bloody feet. A brother’s death. The terrible winter at Morristown followed by the even more terrible winter at Valley Forge. That’s what David Baker endured. I knew that, just as I’ve known for years that not everyone supported the Revolution. I don’t ordinarily get worked up over things that happened more than 230 years ago.

So I didn’t expect to be as angry as I was at the end of the program. I didn’t expect to be as bothered by the whole thing.

I particularly didn’t expect to be sitting here, even now, thinking that something is very wrong when organizations like the DAR and SAR think the payment of a tax ought to qualify somebody as an American patriot. When selling a cow — not giving it, mind you, but selling it — to the American forces qualifies someone’s descendants for DAR or SAR. And looking at the list of eligibility requirements I’m getting even more steamed.

The kinds of service performed by an ancestor that qualifies you to join the DAR includes your ancestor buying his own way out of military service by hiring a substitute or furnishing supplies that he got paid for.10 SAR’s eligibility requirements are a little mushier: your ancestor has to be “a recognized patriot who performed actual service by overt acts of resistance to the authority of Great Britain,”11 which — we saw Friday night — includes paying a tax.

Now I really don’t want to take away anybody’s pride in his own family history. The transformation of the Hessian Johann Christoph Oeste into upstanding American John Christopher East is a great story.

But it’s hard for me to accept it as a DAR- or SAR-worthy story of American patriotism.

Because my family didn’t pay to help build this country in coin.

We paid in blood.

SOURCES

- E.M. Sanchez-Saavedra, A Guide to Virginia Military Organizations in the American Revolution, 1774-1778 (Richmond : Virginia State Library (1978), 29-40, 71. ↩

- See generally Affidavit of Soldier, 26 September 1832; Dorothy Baker, widow’s pension application no. W.1802, for service of David Baker (Corp., Capt. Thornton’s Co., 3rd Va. Reg.); Revolutionary War Pensions and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, microfilm publication M804, 2670 rolls (Washington, D.C. : National Archives and Records Service, 1974); digital images, Fold3 (http://www.Fold3.com : accessed 28 Apr 2012), David Baker file, pp. 3-6. And see Compiled Military Service Record, David Baker, Corp., 3rd Virginia Regiment, Revolutionary War; Compiled Service Records of Soldiers who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War, microfilm publication M881, Roll 951 (Washington, D.C. : National Archives Trust Board, 1976); Fold3 David Baker file, pp. 12-17. ↩

- George F. Scheer and Hugh F. Rankin, Rebels & Redcoats: The American Revolution Through the Eyes of Those Who Fought and Lived It (1957; reprint, New York : Da Capo Press, 1987), 211. ↩

- John Scott Davenport, “Five-Generations Identified from the Pamunkey Family Patriarch, Namely Davis Davenport of King William County,” PDF, p. 27, in The Pamunkey Davenport Papers: The Saga of the Virginia Davenports Who Had Their Beginnings in or near Pamunkey Neck, CD-ROM (Charles Town, W.Va.: Pamunkey Davenport Family Association, 2009). ↩

- Affidavit of Soldier, 26 September 1832; Dorothy Baker, widow’s pension application no. W.1802, Revolutionary War; Fold3 David Baker file, p. 4. ↩

- David McCullough, 1776 (New York : Simon & Schuster, 2005), 281. ↩

- Scheer and Rankin, Rebels & Redcoats, 213. ↩

- See Harry Ammon, James Monroe: The Quest for National Identity (Charlottesville, Va. : Univ. of Virginia Press, 1990), 7-8, 13 (the officers “led the company in a charge”). ↩

- Affidavit of Soldier, 26 September 1832; Dorothy Baker, widow’s pension application no. W.1802, Revolutionary War; Fold3 Bavid Baker file, pp. 4-5. ↩

- “Eligibility: Acceptable Service,” National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (http://www.dar.org : accessed 28 Apr 2012). ↩

- Article III, SAR Constitution, National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (http://www.sar.org/ : accessed 28 Apr 2012). ↩

Amen! I have long struggled with DAR membership because one of my ancestors who demonstrated Loyalist beliefs and abruptly left South Carolina is enrolled in the DAR based on possible participation in the Chickamauga Wars. I am, to say the least, not comfortable claiming him as a Revolutionary War Patriot.

It does seem that those who literally bore, raised and fired arms against Washington’s army ought not be considered Patriots. At least not to the United States.

I do believe in redemption, Susan, so I wouldn’t bar somebody who chose to lay down arms for the British side (Hessian or otherwise) and take up arms for America’s revolution. But… but… but… just on the basis of paying a tax? It doesn’t sit right. For a turncoat to prove he really has turned his coat, I want more than that. Especially (says the purely emotional side) since it was my kin he’d been shooting at!

My understanding is that for the DAR you only need to prove direct lineal descent from a person who supported the Revolution – e.g. was sympathetic to the cause. That doesn’t imply that a person who supported the cause financially was equal to one who fought as a soldier, just that descendants of both were on the “right side” of the conflict. If only military support qualified, then that would pretty much exclude a descendant qualifying on the basis of a female patriot. What seems more inappropriate to me is that you cannot qualify for DAR based on the blood with which your family paid – the service of your uncle who gave his dear young life for the cause. If one of your grandfathers/grandmothers hadn’t also provided military or patriotic service, you couldn’t join, despite the payment in blood. Yet, Rob Lowe could. Assuming that your uncle had no children, he can’t be a qualified DAR patriot. In my (humble?) opinion, that’s where the real problem lies. You should be able to honor your uncle’s and your family’s sacrifice by qualifying for membership through him.

I suspect that, at the core, my problem is with the whole idea of lineage societies. I qualify for dozens of ’em since my mother’s people have been in America since the mid-1600s, and I belong to precisely none. The idea that somebody gets brownie points because of what an ancestor did just doesn’t sit well with me. But as long as there are lineage societies, especially when you get the word “Patriot” expropriated by ’em, I want more than paying a tax… or selling a cow.

Clearly a heart-felt post on this issue, Judy. I’m against lineage societies on the principle that they promote totally false status – or, sta-toos, as a friend of mine says. My ancestors also come from mid-1600s NE colonies, and there are “Patriots” as well as United Empire Loyalists. All I can say is, good for all of them for standing up & sacrificing their lives for what they believed in – we came from good stock, no matter which side they were on.

I accept all these folks as patriots, small letters, to the causes they believed in, Celia — or perhaps simply as faithful to the duties they’d undertaken or been drafted to perform. But calling them Patriots, with a capital P, doesn’t sit well. It just doesn’t sit well.

I’m glad you posted this Judy because I just saw the episode last night and was left wondering exactly what his ancestor did to qualify him for DAR.

I caught something vague about a tax and supplies, but their explanation (if you can call it that) didn’t satisfy me in the least bit.

They really skimmed over the details and went straight for the dramatic, happy ending. I was so frustrated that they did that! I was watching it with a (non-genealogy addicted) friend who was content to see the happy ending…but here I was rewinding the the show to try to see if I could get more details about what they found. It killed me how they little they showed.

So, Judy…he sold a cow, and paid a tax on that? THAT’S what qualified him?

If that’s the case, I’m leaning more toward Judy’s side. It’s still an interesting story because he stayed in the US and appeared to have had a change of heart, but is at as good of a story as they made it appear in the show? And should that make him DAR/SAR-worthy? That part is up for debate.

Aliza, what we know for certain is that he paid a tax. The cow example doesn’t have to do with Oeste/East but was purely my example as an illustration of all that’s required to qualify for DAR-SAR.

Now I’m not saying that there may not be more to this Oeste/East story. But all we know from the episode itself is that he paid a tax. We don’t even know if it was voluntary or compelled. The story overall is a wonderful story. But it sure wasn’t the story of an American Revolutionary War Patriot in capital letters.

Thanks for the clarification. Seems a little wishy-washy to me. My gut tells me that if it were something substantial, they would’ve highlighted it in the show. But the fact that they skimmed over it makes me think that there wasn’t much there to highlight.

Although it was essential to qualifying for DAR-SAR “Patriot” status, it really wasn’t the big deal for the show as a whole.

This illustrates perfectly my reluctance to join lineage societies as well. I’ve put my lines together for a couple of state organizations because the lines weren’t documented elsewhere, but that’s probably the limit of my joining. There are other reasons I won’t go into–but it IS interesting how strongly we feel this far removed from the actual incident. But we do.

We do indeed. Oh boy do we ever… I was frankly astonished by how much I cared… and care.

I sympathize both with you and with Rob Lowe.

That may sound nonsensical, and I totally understand your anger. But what I see in both of you are these feelings: the yearning to identify with our ancestors and support them; the rush of feeling we have when we learn of the agonies our ancestors went through; and our need to settle once and for all that our ancestors were basically good people (and therefore so are we), whatever it takes. For Rob Lowe, the acceptance to DAR seemed to help bring him peace.

These are big, ultimate questions about, exactly, “Who Do We Think We Are?” I notice on that show and on “Finding Your Roots” that people are crestfallen when they find they have ancestors who owned slaves. They move right away either to exonerate them (as Reba MacIntire did, hoping her ancestor was good to his slaves) or to blame them (as Kevin Bacon did, calling that ancestor a “bad egg.”) We all need self-affirmation.

You’re absolutely right that we all need the affirmation, and we all want our ancestors to be among the Good Guys. But what’s more important to me than that my ancestor be a Good Guy is that I be faithful to the truth about whatever my ancestor was, good, bad or indifferent. God knows, I hope generations after me do the same for me: treat me as I really am, not as they wish I’d been.

I happened upon this website after googling around trying to find a possibility that other people would be as dismayed as I am about this story. I agree that it’s an interesting story, but I was left wondering how on earth this Hessian soldier could so easily be “transformed” into an American patriot. The explanation was vague and I am offended by the ending. My ancestor fought in the revolution. I haven’t learned enough yet to know which battles he fought since I’ve only recently begun researching that side of my family. I totally understand the passion and depth of caring that Judy and others feel for something that took place so long ago. I do not belong to the DAR, and after seeing this story, I’m not sure I would want to. Judy, I appreciate what your ancestors did and I care deeply about the sacrifices all our ancestors who fought in the revolution made, as well as our young men and women currently serving. I also appreciate finding a source for venting my frustration.

Patricia, there may well be more to this story in terms of just what Johann Christoph did after he became John Christopher. He may well have done much more that we’ll never know about because it wasn’t documented. But yeah… paying a tax after shooting at my family members does seem just a little trivial to convert a Hessian into a Patriot with a capital letter.

The Revolutionary war soldiers from Hesse-Cassel, AKA ‘Hessians’ became patriots after they were captured, free, and became citizens of the United States as they did not return to Central Europe or what is now Germany, they were land owners and did very well in the United States. Some married other Germans, or completely changed their last names, but the changing of last names from German to English is super common unless you are in Pennsylvania which has always been very German.

I have no personal desire to join SAR, Holland society, Mayflower society, Cincinatti society, FFV, the ancestral group for Karl der Große, Dutch/Belgian/New Netherland lineage groups, New Sweden, French Huguenot ancestral groups, German or other Central European lineage groups, etc. Or more recently the sons of Italy, even though I could easily join all of these groups, I do not have the time to be active as a social member of them.

I have done ancestry research as a hobby in my spare time from the late 1980s until today. I have never been into groups that exclude others or are basically private groups akin to university fraternities.

Female patriots are particularly amazing. My grandmother’s 1896 proof doesn’t qite stand up to today’s DAR standards, I dunno why, but my 6th great-grandmother, Kerenhappuch Norman Turner, was a heroine and even has a statue in her honor. (My blog at http://jglookups.blogspot.com tells some of her story) She nursed soldiers after the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, including saving the life of her grandson. It took him a year to heal, and his children were born after that. I’m sure there were a lot of brave women nursing the wounded, whether their stories have come down to us or not.

LOVE your story about Kerenhappuch — and love her name too! I need to get back down to NC and back to my own family research there. Family lore says we had a bunch of our Shew (probably originally Schuh) family members at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse.

Well, THIS is interesting. First, I’ll say I DVRd the show, so I haven’t seen it yet. I’ll be kicking my husband out of the living room momentarily.

I AM a member of the DAR. I chose to become a member mainly because it was a dream of my Mom’s to be a member, and I felt it was something valuable we could do together. As I was researching to put my application together, I perused old applications available for research purposes. There is much historically wrong with the manner in which applications were dealt with in the DAR. In my experience, prior to about 15 years ago, the application process was ripe with problems. As in my own case, I uncovered a book written in the mid-nineteenth century that was missing an entire generation of a family. That book is STILL being used today by researchers.

And, you are correct in saying that actual military service is not the only way that you can “prove” your ancestor was a Patriot. In my case, my ancestor did join with the New Jersey Regiments; he was a Private and I have done no further research into how he actually participated.

I’m proud to be able to say I’ve had a relative fight in every war this country has fought, up to and including current service. What’s more, currently, the DAR does so much good work to support our troops, and for that alone I’m happy to be a member.

However, Judy, as you were relating how you felt I was right with you. It seems unconscionable that someone would even attempt to imply that paying a tax equals blood shed for our liberties. I certainly can’t change the manner in which members were accepted prior to my joining the DAR. Do I wish their membership criteria were different? Indeed I do. So, how do we change it?

Laura, the only two ways I can think of that anything ever gets changed:

(1) People on the outside say they don’t like it and won’t join with any group that does it. I guess I’ve staked out that territory for myself.

(2) People on the inside say it’s time for a change. Looks like that territory is up for grabs!

Through the years, I’ve also started and stopped several times to join lineage societies as I’ve a few ancestors that qualify me. It’s always been good enough for me that I know.

Then this past Saturday I sat next to the regent for a local DAR chapter at my local genealogical society meeting, and she really wanted to get me in, so to speak. So, I’m gonna do it mainly because it’ll be nice to get to know her and others locally who have the same interests myself. We’re from Texas, and in Texas the ONLY lineage society that matters here is the Daughters of the Republic of Texas. If you’re not DRT, you’re really not that special [which is VERY wrong], but it’s true.

I also have a Loyalist [and that’s a capital L]. War is not black and white. Many at the time of the American Revolution had torn loyalties, and without firsthand journals and letters, we really don’t know what was in any of their hearts or in their heads. What were their feelings on all of the issues?

My Loyalist wasn’t a soldier. He just supported the other side, and held to that support. [And I don’t know what kind of support that was.] But since he [I’m assuming] was so set in his beliefs, he and the family lost their land and home in Connecticut and relocated to Noyan, Quebec.

I’m all over the place on this, but I’m not angry. My Loyalist’s father had been the town doc in Fairfield his whole adult life. He and his family had strong ties in the community. I think I just feel bad that things escalated so badly that there was war and death at all.

I’m proud to be an American. However, I don’t think war can be simplified into an ‘us’ and ‘them’. It makes war a little easier when we can say there’s good guys and bad guys and a right and a wrong.

This country’s forefathers saw revolt as a last resort solution. They were deeply conflicted by the decision as well as they should’ve been as evidenced in their letters to each other on the matter.

Many fought and died for what they believed in, but there are others who had other reasons to fight just as there are today in modern wars. Without some firsthand evidence of how our ancestors felt and believed, we’re left with making conclusions based on evidence and circumstantial evidence.

I agree that a tax record and a change of heart is weak. Just because he became an American citizen doesn’t mean anything. We just don’t know without something else. But these are DAR/SAR’s requirements that we’re talking about.

Which leads me back to lineage societies. Where do you draw the line for membership? I dunno, but they did. Perhaps another lineage society could be started that requires other evidence of patriotism. Something more concrete. However, no matter how you define it, there will always be someone criticizing the definition.

Unfortunately, DAR is like the Mayflower. They’re just more well-known by the general public. There are many lineage societies that have more stringent requirements for membership. And, really, my going for my DAR membership is just one stop on my lineage society journey. I’ve some colonial ones that I’ll be doing, but I’m totally fascinated by the Winthrop Society, for which I’ve 3 avenues to get into it. For whatever reason, I’m more excited by that and UEL than DAR.

But why do it in the first place? Just a personal preference. My family tree is what it is regardless of a lineage society membership.

Oh, and to be contrary, I’m going to do my DAR application at the same time I do my United Empire Loyalists application. It’s who I am. Literally.

~Caroline Pointer

Unfortunately, DAR is like the Mayflower

Yup. Exactly. The 600-pound gorilla in the middle of the living room, and it sits anywhere it wants. If your application is accepted, of course, you can work to change it from the inside… not that I’m hinting or anything…

And I absolutely LOVE that you’re doing BOTH the DAR and the UEL at the same time.

I belong to Mayflower, not DAR, but we certainly have state and General Society meetings to change our by-laws and make amendments. It sounds like this is a case of perhaps advocating for changing membership rules. In Mayflower it used to be the case that one had to join through a MALE passenger, but just a few years ago the rules were changed to ANY passenger (male, female or child) on board the Mayflower. My daughter turned 18 just in time to join Mayflower under her female ancestor, Mary Norris, wife of Isaac Allerton. Perhaps DAR is different in that they accept a wide range of lineages, and Mayflower Society membership is only descendants of 102 known individual passengers on board the ship. One has a loose definition, and the other is rather strict.

Heather, if the lineage societies want to change, they certainly can do so. I think what troubles me here is the implied value judgment that goes along with the word “patriot” particularly when it’s capitalized.

Judy,

While I agree with your sentiment about the illegitimacy of Lowe’s “Patriot” ancestor, I do not agree with your view that people join lineage organizations just to “get brownie points…because of what an ancestor did.”

I am a recently inducted member in the Sons of the American Revolution. For weeks I stressed myself out over whether or not I should even go to the induction ceremony. I thought to myself “why do I want to be awarded for something my ancestor’s did…after all, he fought, not me!”

But then I remembered why I joined the society in the first place: history. I wanted to join because it was a source of pride for my family. Not because I had joined but because I had a family member who championed all the ideals I feel so strongly about.

As one commented above me, this is not about “false statuses” but something much larger. I don’t brag or wear around my SAR pin or prominently display my certificate on the wall. For me, it serves as a reminder of the sacrifices made by my ancestor. It also serves as a reminder for my kids and their kids that they ought to be respectful of the past achievements and hard work of their ancestors. Likewise, it promotes the continuance of some of the greatest ideals ever conceived by one nation.

Your reason is the only reason I can imagine for having lineage societies at all, Tim. Nothing that makes us mindful of those who came before can be all bad.

My family came over on the Mayflower. My family fought in the American Revolution. Some died. Most of them gave their money, families, homes and royal titles for Liberty for each one of us. I belong to DAR because of what my family sacrificed for this country and each one of us living the dream they dreamed for us. I am proud of their sacrifices for us but as many did they got back on the ship and went back to England to avoid loosing their lives, family, incomes and titles. Some wouldn’t blame them, I know I don’t because so many seem to not understand the awful lives that came after the American Revolution nor do they appreciate their freedom or the sacrifices made. It seems expected. Congratulations you’re an American born free because of my family who did not run away to save themselves. Their entire lives were sacrificed for each of us. Amen!!! Love those soldiers with or without money! Love those men with or without titles. I wouldn’t be here without one of them.

I am certain there are many wonderful organizations and that they do a lot of good. You have aptly described why I don’t join them, in spite of being well-qualified.

I have many cousins who have joined one of these, and one who was an officer of the SAR in Texas and who is very proud of it. I honor their choices. I can’t make the same choice for me.

What a powerful essay! I knew there were problems with the DAR/SAR but since I have never had a desire to join their ranks I really didn’t research it for myself. I can really “hear” your heartfelt emotions in your writing. The story is very sad, made sadder by the DAR/SAR policies.

Michele

Thanks for the kind words.

Lots to think about here…

I could join the DAR thru several lines if I wanted to (including one that has not been documented in their records) but as yet, I have not. I also have documented Loyalist ancestors from the Yonkers, NY area that would enable me to join the UEL society. These ancestors moved back to RI in the 1870s. I think Tim and Caroline have the right idea – our history as a Nation is complex and so are our personal family histories. I think that point alone is a good teaching point for the next generation and providing the evidence to my descendants that our family supported both sides during the Revolutionary War is a good starting point for thought and discussion about how we came to who we now are.

Having said that, I agree with Judy and had the same reaction she did to Friday’s episode, although not nearly as strongly. I understand that Rob Lowe’s ancestor came to fight in a land he probably knew close to nothing about out of economic necessity (as a landless youngest son) and chose to stay because there was nothing for him economically back in Germany. Here, there was land available to almost anyone. He probably made a decision based at least partly on economics, and also probably became a proud American at some point. However, I think there were a few years between those points, and going from Hessian mercenary to paying a tax within a few years, does not make one a Patriot (with a capital ‘P’).

Thanks for a thought-provoking post and discussion.

Thanks, Wendy. One of the benefits — and drawbacks — to being such a diverse nation is that our stories and interests often work at cross-purposes. But all of our ancestors made us who we are, and this country what it is.

I would suggest that you join the DAR, simply to document your unknown-to-them ancestor. You don’t have to be active, or recruit, but you would be saving your research for future generations.

My only known Revolutionary ancestors are already known to the DAR, and apparently correctly documented in their records.

So those who fought for America to become a republic = good and patriotism, which = freedom. Why? Were those who wanted it to stay a British territory or eventually a “dominion” like Canada all wrong? It is a case of the victors deciding who is good and who is bad. Some of us have had relatives on both sides of a cause. I don’t regard one as right/good and the other as wrong/bad. They were just people often joining because of coercion, economics or other non-politically/patriotic reasons. Besides what does this have to do with the living descendants? Are we good or bad based on our ancestors’ actions? Seriously? I would think it based on our own.

Xenia, you’re absolutely right that the victors write the history books. (Just ask members of the Richard III Society!) But here we have a case of definitions: by definition patriotism is love of and support for one’s country. When the DAR and SAR were formed, the country on whose behalf acts would be judged for patriotism was the United States. And patriotism in that context has to mean the revolutionary cause.

By the same token, there were good reasons that many people had for staying loyal to the Crown — and they’re not called traitors, they’re called Loyalists, for that very reason. Had the colonists lost, they would have been traitors. No two ways about it.

I agree that societies can make their own rules as to who can belong but not to label those who do not qualify as bad. Why should Rob Lowe feel bad for what his ancestor did? Rob is not his ancestor. Does Rob qualifying on the basis of his Hessian ancestor paying a tax such a terrible thing? It seems like a petty reason to allow him membership but the quarrel should not be about Rob’s Hessian ancestor being “bad” and trying to kill your ancestor. It should be with DAR/SAR on their rules of admissibility based on the amount of contribution to the Revolutionary War. So I agree with your call for examination of their rules but sans the emotion around your ancestor versus Rob’s ancestor. Who knows how many people have had ancestors meet face-to-face in a war and each try to kill the other because that is their duty as a soldier.

Nowhere have I divided the world into “the good” and “the bad.” The ugly, maybe.

Bad, good and ugly are subjective terms and I am trying to make this a rational argument. I agree if the roots of DAR/SAR are based on the Revolutionary War (and they are), then their standards of admissibility should be more firmly entrenched in the role of the person in the Revolutionary War, but did you not say somewhere in your article or above, that you did not believe in joining such societies, which would mean you question their validity? If so, why are you upset with them?

Perhaps you might care to go back and read the blog post again. The crux of it is that this is not a rational argument or a rational response. It was, and I quote: “an absolute gut-level visceral reaction I never would have expected.” And perhaps you might care to explain just why someone who isn’t a member of a group shouldn’t be able to criticize its standards. I’m not a member of Congress but BOY am I ever upset with THEM too.

Well this last response of yours made me laugh out loud! In response I would say that you are not a member of Congress but Congress works on your behalf as a citizen but DAR does not work on your behalf if you don’t believe in such societies nor are a member of them. Since you are not part of their society, they do not rule over you and so are not answerable to you nor you to them. You are a citizen of the United States and Congress acts on behalf of the citizens of the United States. However, your gut-level visceral reaction is your right to feel as a human being. I just don’t think it means anyone has to do anything or feel bad themselves because of it. Anyway, on this matter I am bowing out now.

I enjoy your blog, your post, and all of the responses! I see both sides of most issues, which makes it challenging to come to gripes with one’s individual beliefs about anything. Yet, what I’ve found most fascinating by this post and subsequent comments is that you described some of your emotional journey watching the Rob Lowe episode of WDYTYA and how is brought up emotions for you regarding your ancestor. This to me is one of the major cornerstones of doing genealogy. With every document or discovered piece of our ancestor’s life, we are invested and brought into the story more deeply than just knowing the blood line connection through the family tree. The amazing part for me is what brings me to tears in every episode of WDYTYA or Finding Your Roots for example is observing these people finding those discoveries about their ancestors and taking it into their life like every genealogist does every time they discover another record or photo or ephemera or whatever that moves them with another aspect of their ancestor’s life. It was amazing that you had emotions as if your ancestor was sitting on the couch right beside you watching that particular story together. And you felt every emotion that that ancestor’s crumbs of a legacy left behind for you to get to know their story with your heart, mind, and soul of what those experiences must have felt like. That was what was so special, not the debate of some lineage societies membership requirements. Although, I learned a lot more about those lineage societies and their historical story-telling importance as a way of honoring your ancestor. Yet, I was moved by the fact that right now you would stand up for your ancestor and emotionally defend their value for their important life. Those that do genealogy care very deeply for our ancestors (good, bad, indifferent, or whatever description you want to tag to them). We may not always agree with things they’ve done, said, or whatever, yet we still love them dearly. I believe that Rob went on his own emotional journey as the process unfolded and we only saw a glimpse of it in truth, just like I saw a glimpse into your family’s history with your post. And for that, I thank you for sharing your emotions and story just like I thank Rob Lowe and every other person that shares their family’s stories as well. We are on this journey together, learning, loving, and living to which every person is important and valuable and to be honored for their teachings that will someday become those stories of “those that came before us”. Thank you for sharing!

Oh Skeeter… you got it. You really got it. And said it maybe better than I did. It really is the personal journey and the amazing, astonishing and really wonderful connection genealogy gives us to our past that keeps me hooked. These are OUR people, and the fact that they touch us so very deeply when all we can know of them is a line in a pension application is what keeps me going back to the records time and time and time again.

I have at the lest 3 RW ancestors all on my dad s lines. Am I pround of that, YA BET. I am as much pround of the farmers, pipfitters and ministers that run in those lines and some being my DIRECT line. God Bless each and everyone. My mom s lines…Casle Gardens and Ellis Island to New Jersey..before tht Salerno, Italy. My grandpa, who died before I was born came with his siblings thru Ellis Island when he was 10 years old, June 8, 1892. While genealogy sires emotion , often emotions you dont exspect….I became an emotional mess..in a good way, the day I held my grandpa s passinger list in my hands..I was excited, I cried and tried to image a 10 year old boy makeing such a journey , into a strange ew land and new way of lie. There was joy in the fact I could gift this to my 84 year old mother. For me, it s not how long your people have been in America, it s thier journeys , stories that causes the rush of emotions. I honnor my Casle Garden and Ellis Island ancestors just as I do my RW ancestors, with love and apppeiation. God Bless them ALL. They all had a hand in my exsistance

I’m definitely with you there, Robin. My father and grandparents were immigrants as well — my father not yet four years old.

Judy and others,

I do not belong to any lineage societies, but I think eventually I will. Not for status (I don’t even see it as status), but because those preserved records are guideposts for other descendants of the same ancestors. I descend from John Alden, and my branch is one of the “lost” branches (to the John Alden Society, not to me). I keep thinking it would be nice to do the paperwork that would let “my folks” take their proper place among the other descendants. Once your line enters the records of, for instance, the DAR, or the Mayflower Society, it is there for someone else to find.

Janis, I’ve thought on occasion of trying to at least correct some of the mistakes made by applicants in the past. At DAR for example they have a flag on an application submitted on David Baker’s service because a later application through the same son (William) showed that the first applicant’s William couldn’t have been the son. The second applicant was right — but the first applicant IS a David Baker descendant as well. The first applicant simply skipped a generation — her ancestor William was David’s grandson (son of my third great grandfather Martin) rather than son.

Exactly. Kind of nice to do “our folks” that favor. A lot of other things on my list first, however. 🙂

What, you mean (gasp) you don’t have unlimited time????

What we know as the American Revolution was a very unpleasant, very personal civil war. Up-close accounts like _1776_ show how improbable the actual outcome was. The “smart money” was on the British Empire. If that much is accurate, then I can understand how a lineage society might choose to honor anyone who took any kind of stance in favor of such an underdog cause. (And for those seeking to change that choice, if you really want to stir up a hornet’s nest, propose that *adopted* descendants of patriots be allowed to join!)

And if you REALLY want to stir up a hornet’s next, propose that DNA can take the place of a paper trail!

Amen!

I am both a professional genealogist specializing in Virginia and a former member of the genealogical/clerical staff of the DAR, so while, as a male, I am not eligible for membership in the DAR, I have a perspective few do to comment upon the same.

Your observations about the rules of eligibility for the DAR in particular do not begin to touch upon the willingness, at times, of that group to violate the spirit of the same when it suits an agenda, sometimes of a single individual, other times a larger group.

First, the DAR includes as qualifying service participation in the Battle of Point Pleasant. Point Pleasant was fought 6 MONTHS before the Battles of Lexington and Concord, almost universally recognized as the start of the American Revolution;

Second, the DAR recognizes, in clear violation of its rules, one John Grumbles of Maryland as a soldier. While there is no dispute the man served, by the same rationale that saw his service recognized, Benedict Arnold would also qualify as a DAR soldier!

Third, “proof” of the eligibility of the Revolutionary War service of one Samuel Darby of Connecticut was forged!; and

Fourth, the admission of the first black member of the DAR violated its own rules about no illegitimate issue!

Though Point Pleasant was fought in direct opposition to Treaty of Fort Stanwyck that forbade British settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains, and resulted in many Indians allying themselves with the British during the Revolution, “American” forces were led by Lord Dunmore, Royal Governor of Virginia and it is widely acknowledged that Dunmore was heavily invested in land speculation in the very areas where the Treaty of Fort Stanwyck prohibited British settlement. Finally, while later Revolutionary War pension applications do mention fighting at Point Pleasant, the majority were rejected either specifically because the federal government has NEVER recognized Point Pleasant as part of the Revolution and most applicants did not meet the minimum service requirements–service at Point Pleasant would have been considered “militia” service, and it was not until the Act of 1832 that anyone with strictly militia service could be pensioned, plus, participation strictly in Point Pleasant was of too short a duration to qualify for a pension.

My understanding is that Point Pleasant was included as qualifying service because some influential founders of the Society would otherwise have been ineligible for membership and it remains a qualifying service to avoid the embarrassment of having to admit those founding members were not eligible.

I was the staff member who originally processed the application on John Grumbles and I REJECTED it on the grounds that the one piece of evidence establishing the fact of the service also included details that would have resulted in the man likely being executed for for being absent without official leave, insubordination, sedition, and assaulting a superior officer had he served in the Continental Line (regular army) rather than the militia. The applicant’s response to my point the same out was those terms were “not used” in the submitted proof. Shade of PATRIOT versus patriot–how else would one describe being summoned to the captain’s office to explain why one was not participating in training musters and refusing to give an answer than “absence without official leave”? I was subsequently told my endorsement was FORGED to the application because of the fact the applicant had a National Officer as her sponsor.

Samuel Darby was recognized by the DAR as a soldier many years ago. When an application came in while I was on staff, I was struck by the fact that first, though the man lived in southwest Connecticut, the service claimed for him was in the immediate area of Boston, second, the man would have been only 6 years old at the time of his enlistment given the date for his birth cited in a genealogy written by the man’s own son, and third, he lived long enough to have qualified for a pension but there was no evidence that he ever applied.

Since there was a means test for pensions, he might simply have chosen not to apply/try to misrepresent his need, but not only did the genealogy written by his son give a different, and substantially later, date of his birth than DAR records, but that son spoke of an uncle who was a surgeon in the Connecticut Line who died during the Revolution, but never mentioned his father’s own service, something that seemed highly improbable. Checking the files for any additional evidence that may have been submitted with the original applicant’s paperwork, I found a photocopy of the page from the family genealogy with the year of Samuel Darby’s birth altered, and rather crudely, to read 1759 rather than 1769! With this discovery, Samuel Darby is no longer recognized as a Revolutionary War soldier.

I was no longer on the DAR staff when the Society admitted its first black member, but I was still dating a former co-worker and also remained friends with a number of colleagues. Several told me that the member in question was descended from an inter-racial “marriage” which occurred in Ohio about 1805. While the applicant’s descent from the couple was unquestionable, no proof of the marriage was ever found. Ostensibly, it was ruled that the record likely did not survive and other evidence that the parents lived together as husband and wife sufficed to prove the marriage. However, this IGNORES the fact that interracial marriages were ILLEGAL in Ohio at the time, thus no record was ever found because the marriage was common law, and thus unacceptable under Society rules!

I would also like to comment about the “donating of supplies”. Those supplies were frequently collected by ARMED men. How many people would have refused to “give” supplies under those circumstances?

I understand the rational of including serving as a juror, justice and in other civil offices, as well as providing supplies, as there is an implicit acknowledgment of the legitimacy of the “revolting” government, but it also bothers me when no effort is apparently made to dig a little deeper to determine if there was a larger “truth”.

Thanks for a first-hand perspective, Michael.

Dear Judy, thank you for writing this. Just wanted to quickly say that I am descended from Charles Shaffer of Pennsylvania, who was a mattross in the Continental Army and served at the Battle of Brandywine.

I have no way of proving that your ancestor and mine had any interactions while they both served in the same war together, but Charles also spent that horrible winter at Valley Forge, half frozen and half starved.

And I agree that any decent genealogist does seem to be awfully protective of their ancestors!

(His descendants now number in the thousands.)

Judy, I’m repeating myself from Facebook, but I don’t understand why a German mercenary would qualify as SAR. Don’t bite me 🙂 but for instance, the United Empire Loyalists’ Association of Canada (our lineage society) makes a distinction between Loyalists and soldiers who were paid to fight. Hessians who settled in Canada are not considered Loyalists. Nor are British Army troops. Does the DAR accept Lafayette’s soldiers as Patriots if they stayed behind to live in America?

The eligibility requirements here are very different, Brenda, and yes, absolutely, Lafayette’s soldiers would qualify. And they don’t even have to have stayed behind to live in America. The websites of these organizations suggest that descendants of someone who fought for the revolutionaries and then went home to his own country and stayed there would qualify.

I should have added, I believe many of us can identify with the visceral reaction so well expressed in your post. I’m also learning from the comments; thank you!

Thanks, Brenda — I really did want to get that gut reaction across first and foremost.

I was also struck by the apparent ease with which the DAR, and then the SAR, would have accepted Mr. Lowe’s ancestor as qualifying him for membership – and without an application or apparent sponsor, no less. Payment of ‘taxes,’ in an area and at a time where non-payment owuld likely have severe consequences, seems a rather thin basis on which to base member and demeans the servies of those with ‘real’ military service.

Here’s two examples:

1. my 5X great grandfather was a Lieutenant in an (American) militia unit in Westchester County, New York during the Reovlution, but in 1781 joined Delancey’s Brigade, a somewhat nortorious Tory calvary unit. Predictable result – he would up in New Brunswick as a Loyalist in 1783, and has been used by others to clain membershiop in the UEL. I wouldn’t dream of using him to claim membership in the DAR or SAR – but would be be ineligible by reason of his later British service, as opposed ot the earlier British serviced or Mr. Oest?

2. another ancestor from just ouside Pennsyvlania and paid taxes during the Revolution (appears on tax rolls to 1780), but served in a Britith militia unit, was attained as a traitor by the Pennsylvania Lehaliatuire which ordered his property forfeithed, and alos was a Loyalist, settling in New Brunswick.

Would the DAR/SAR accept these invididuals? I would hope not. (I do have other – nontainted – lines to claim DAR/SAR membership.)

Good questions, Ken. I suspect the answers depend on the order of service: British first, American second okay; American first, British second, maybe not.

Actually, the DAR does recognize the “allies” as qualifying ancestors for membership and the Society actually has a chapter in Paris that consists of both French nationals and Americans living overseas. I am aware of this because while I was on staff at the DAR (1974-1977), I was the only one able to read and write French, so I processed the applications that came in from that chapter!

Michael,

Just wanted to give a shout out from another former DAR staff member. Although I was there a little later 2003-2005.

Heather

Michael:

Now about the Rob Lowe justification regarding DAR & SAR. Yes, we all love a good ending. I had a personal feeling with this to begin with because the Presbyterian Church they were sitting in to show Rob his tax list, was the church my son & daughter-in-law got married in. Then, when I could see that this was just to expound on something to make Rob feel good about his ancestor, made me feel angry at ancestry.com and NEHGS, of which I have been a paying subscriber since the ancestry.com inception, and NEHGS for at least ten years. Up until this show, I had high regard for work done by the NEHGS. Josh, you disgraced yourself, and everything that I thought that NEHGS stood for. Supposed high standards in tracing genealogy of members, and the requirements you place on members submitting stories. I had Loyalist ancestors, and I realize at the time everyone had their own opinion on what they thought was right and wrong. This show solidified my reasons as to why I will never apply to the DAR. I feel there needs to be a serious apology from NEHGS, and D. Joshua Taylor for this very lame reason to make the overall audience “feel good” about something that was not so good. It is like slapping my father in the face for fighting in WWII, & being faced with killing German soldiers, otherwise he would’ve been killed, & then allow that German to move to the U. S. & tell him it was okay. Nancy

Thank you for you explanation of the SAR membership thing. I thought it was “manufactured” so Lowe could join.

I don’t know why the story had to go that far. It was interesting to hear the story of the Hessians. I would have preferred a “redemption” arc, i.e., following his capture, moving west (was he a pioneer in Ohio?), etc.

Ann, the Hessian story by itself was great. I loved it. I have tons of German ancestors so I’m sure interested in German history especially as it intersects with American history. The DAR-SAR part… well… if I ran the WDYTYA circus…

Regardless of your emotional take on the outcome of the show & the fuzzy research, it was a great story. Did anyone else notice that in the German parish register, the target person was actually NOT born as Christopher, but was born as a Chrisophel? This supports the later Stophel USA findings. GermanGenealogist.com

I didn’t know too many German Christophers! So the process by which the names were Anglicized — “Christoph Hesion” to “Christoph Oest” to “Christoph East” — made perfect sense to me, as did the change from Johann to John.

Judy, I commented yesterday about how I can totally relate to your feelings about this story. After going back thru some of my research and refreshing my memory, I confirmed that my 4x great grandfather, Col. William Montgomery, was a member of the 6th Virginia Regiment. His pension application states, “He was in engagements at Trenton and Princeton, was at Saratoga at the taking of Burgoyne, and had a hard engagement at the White Marsh”. Another 4x great grandfather, Abraham Estes, was also a soldier in the Revolutionary War. I am so proud of my ancestors, and in doing family research, I’ve been surprised to realize a new love and respect for my family members from so long ago. It’s a connection I can’t explain, but it is oh so real. Thank you for allowing me to be a part of this discussion.

Thanks for joining in, Patricia. Amazing, isn’t it, how we feel those connections to people we never knew.

Just read the Legal Genealogist article about the Hessian who became a Patriot. I was deeply offended that the writer did not think the man worthy for DAR or SAR honors. The American Revolution was very gray at best! There was no black and no white when it came to who was right and who was wrong. The Loyalists were abiding by the law(s) of the day. The Patriots were breaking the law(s) of the day. The records seem to indicate that the VAST MAJORITY of the citizens of Tryon County knew very little of the reasons for the conflict. The Loyalists knew that they were in danger of having their homes and land seized if they did not Rebel. The Rebels knew that to stay behind and avoid the call to defend King and Country endangered their lives and that of their families. It is my impression that the average German in Tryon County who remained behind in the Mohawk Valley was fighting mainly to protect his home and his family. The average German knew nothing of the concept of “liberty”. Interestingly though, the German settler was more likely to own his or her own farm or acreage than the Scotch, Irish, or English settler. This may, to a degree, be a reason for Loyalism versus Rebellion. However, this theory falls short when one looks at the Herkimer, Young, and Nellis Families amongst other German Families that fled to Canada. I have two more weeks of College classes to survive and then I can start thinking about this again. In the meantime, do us all a break and bury the hatchets, muskets, sabers, and one up-man-ship and treat our Loyalist and Rebel Ancestors with equal admiration and respect. After all they only had one thing in mind: “What is the best action for me to take to preserve my rights and the safety of my family.”

I’m not sure of your point, Ken. It seems like we have the Loyalists-versus-Revolutionaries issue mixed up with the Hessian-paying-a-tax issue here.

The WDYTYR story was interesting–as they always are–but the letters from the DAR and SAR were a cheap promotional scam of both organizations that I am annoyed and sad about. I may

have paid my last dues to DAR as a result of that insulting move on their part to equate fighting against our revolution and then paying taxes with the six years of sacrifice made by my grandfather who served with Washington.

I think your comment proves part of my point: how emotional we can all get when dealing even with the distant past.

I’ve loved reading the initial message and the follow-up comments. I too have a “Hessian” ancestor. His descendants have been tracking him for at least 3 generations. In 2007, I was the lucky one who actually discovered his true German name (written nothing at all like the Anglicized version). Anyway once that was found, we hired a German researcher who found the church where he was christened and where his parents are buried. In October, 15 descendants will be going to Germany to re-trace some of his early life.

I put “Hessian” in quotes because it is a misnomer – many of the German soldiers were from other areas. Mine was from Anspach. Also they were not mercenaries. These were mostly poor young men who were conscripted by their prince. The prince was the one who received the money who typically used the money to pay off debts from other wars. Had the soldiers gone back to Germany at the end of the Revolution they could have easily been conscripted again to fight somewhere else. My Anspacher was captured at the Battle of Yorktown, sent to the Winchester POW barracks. A few months later the POWs were marched from there to Baltimore to go back home. We know that he was with them at the beginning of the march but never made it to the ship. A few months after that, he shows up in Shenandoah county marrying a local German girl.

This is really just comments to say that the German soldiers were not necessarily fighting of their own accord but because they were subjects of greedy princes.

Frieda

Great story, Frieda — and oh… do I ever envy you folks that October trip!

My brother is in the SAR and I am eligible. However, after watching the Ron Lowe induction to SAR without a sponsor and for having his relative only pay forced taxes after fighting Washington gives me pause. Therefore, all Tories who later paid taxes should be eligibile for membership in DAR/SAR correct? As someone previously stated, this was a promotional scam for the actor and program to have a happy ending.

Just to be accurate here: Lowe wasn’t inducted into SAR, he was simply invited to apply for membership and told that his ancestor would be recognized as a Patriot if he chose to apply.

Who told Rob Lowe that his grandfather would be considered a Patriot based upon him paying taxes? Was this a spokesperson for SAR to the producers of this show? The paper trail provided by this show supports his induction. Can we verify if he is inducted. Thank you.

You should certainly be able to verify his status with the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. But my recollection — just from having watched the show (and memory can surely be wrong!) — is that he was merely invited to apply.

Thank you, I will research it further.

I just finished reviewing the tape of the show. DAR verified that his 5th grandfather paid taxes in 1782 and was considered a Patriot by their organization. They provided paperwork on his behalf to SAR. SAR sent Rob Lowe a personal invitation, that he read on the show, to apply to SAR as they had verfied and accepted the work of DAR. This was a personal letter invitation to Mr Lowe signed by Mr Larry Magerkurth, executive director of SAR. I think anyone who paid taxes in 1782 in the colonies and have the paper trail to prove it, would be eligible. It will be interesting to see if Mr Lowe completes the application process.

Thanks for confirming my recollection.

Skip Gates’ last PBS Roots is worse than this episode of WDYTYA.

I’m not sure I see the comparison, good bad or indifferent.

I don’t see the paying of taxes in 1782 as such a patriotic thing. The last major battle of the Revolutionary War was fought in Yorktown in October 1781. There might have been skirmishes following, but I don’t think he risked too much being on the American side.

The timing surely does complicate the analysis.

Oh, my, Judy! We do so KNOW those ancestors sometimes! I’ve started teaching history to my kids using the genealogy chart on the wall. I hope that they will get to know their ancestors well enough to feel as strongly about them as I do. I think some of the best things about the black sheep is all the news I get about them. The more I have to work to find out about the ancestor, the more possessive and protective I feel about him.

It’s hard to explain just how we get to feel so protective, but oh my… we sure do.

You are lucky to have documents written by your ancestor that tell what he did in the war. I have at least seven ancestors that served in “military” positions during the war, but the exact details of their service are not so well documented, so we have to guess by which unit they were in and what the officers of those units did. I have another non-military ancestor that paid taxes, but his son and son-in-law were soldiers. He was too old to fight, but his heart and support were with the revolution.

Also, about those folks who paid someone to serve in their stead — usually it was not an act of cowardice, but pure practicality, being needed to work the farm or some other critical occupation or not being healthy enough to suffer the rigors of soldiering. It provided a willing soldier while the farmer provided critically needed food and horses, or the smithy provided critically needed plows or wagon parts, or the a miner provided saltpeter for gunpowder. It takes a brave man to stare down a bullet or bayonet, but to win a war it takes a lot more than soldiers. During WWII, one uncle went to fight, one uncle stayed to work on the farm, and my dad built tools to make the machines of war. They all paid taxes. So, which could you fight a war without – soldier, food, guns, or money?

Every citizen is required to step up to the plate in time of war. Every wife who stayed home and took care of the children while her husband went off to war, every grandparent who stepped in to assist with the care of the youngsters — the list of those who deserve credit for what they did is almost endless. But that’s not the question here. The question is whether we, in the 21st century, create “patriots” out of those whose service consisted of paying a tax at a time when the outcome was hardly in doubt.

I am a member of the SAR and I understand where you are coming from. The DAR and SAR are more than a lineage society. They are Congressionally Authorized. They are patriotic and their meetings are about the history of the cause. I enjoy the meetings very much. There are many lineage societies but most of them are not Congressionally authorized or have meetings that deal with the history. I am a member of The General Society of the War of 1812 as well and it is way more strict about who can join. The same goes for The General Society, Sons of the Revolution.

I appreciate your decision to join in the conversation, Elijah.

Or, you could be like me and have ancestors on both sides of the conflict. I have a Hessian who stayed in the U.S. and multiple Revolutionary Soldiers in my family tree.

I don’t get angry thinking about what the Hessians did. Many joined the military because they felt powerless to better their lives any other way — not super heroic but at least understandable. People on both sides were killing. However, Should the Hessian be named a Patriot? No. I think the Hessian part would outweigh the tax part. Just like Benedict Arnold shouldn’t be a DAR/SAR Patriot even though he did a lot of good for the Patriot cause — before he did a lot of bad. Nor should he be an English hero. His story is too complex to be on anyone’s list of heroes.

Making it so easy for a known enemy to redeem himself makes it seem as though one only needs to live in the right place at the right time and have a paper trail to be a “Patriot”. I hate to think the DAR/SAR is getting desperate for members. The societies are supposed to be about honoring our ancestors for what THEY did. It is about their service and sacrifice — not our desire to be in a society.

Let’s just say that if I ever do join the DAR, I won’t attempt to join under my Hessian, regardless of whether he payed a tax or not. Doing so doesn’t seem very patriotic.

Thanks for your comments, Elizabeth. I agree that the issue is complex… and appreciate that you don’t think your Hessian should qualify.

Your blog post doesn’t seem to have much of a point. Was Rob Lowe in the SAR or trying to join? This post sort of seems like you want to tell people about the price long lost relatives paid while at the same time pretending to be above the DAR or SAR. Maybe I just missed something but it just seems tacky. They are just organizations that people join. They could be flawed but do you really care? If you’re not interested don’t join.

If you’re not sure if he was or wasn’t trying to join the SAR then, yep, I’d say “missing something” is an apt description.

Hmm – yeah I didn’t see the episode or anything. I was just going off of the information in your poorly written blog post. Oh well.

I’ve traced my family back many hundreds of years and was very proud to find that so many of my relatives had fought in the Revolutionary War. I was going to join DAR but after seeing Rob Lowe episode I was very upset. I dont know if I should join DAR now. I think my relatives wouldn’t like that. If fame money whatever can allow Rob Lowe becoming a member I think they would not not want me to join. Standing up for my relatives hundreds of years later, am I being too emotional? Btw I do like Rob Lowe.

I was that emotional as well, Debbie. It surprised me that I reacted that strongly to something that happened so very long ago, but that’s what family history does to us!

Go ahead and join because you have the proper documentation. Rob’s admission was sketchy, but apparently acceptable. If you feel it doesn’t meet the sniff test, then the only way to change it is from the insde.

Like your ancesters you have to pick your battles.

The remark that Bennedict Arnold would be eleeigilbe for the DAR as a patriot is patently false. The DAR looks at the last act. Arnold’s last act was as a traitor. Also, it is false that children have to be legitimate. Perhaps these wee old rules, but having just finished the DAR’s geneology course, these are not the standards. standards for geological proof are much stricter now than in the past. On the whole issue of what counts as we vice, yes providing supplies that the person was paid for is acceptable service; so is paying sully taxes. There are other societies that have different requirements- these are services that are acceptable to the DAR. Three are other socieites, like the Society for Descendants of Washingtons Army at valley Forge that do require a fighting person.

I chose to join to honor my ancestors and I find each that I resaerch becomes real to me and I feel like I actually know them. That is the great thing about genealogy to me. the patriot I chose to use to join the DAR was a Seargent. I wanted to join with a solider. It have three supplementals penning, one for a Captain who was at Valley Forge; the other two were older and provided supplies. Without supplies , taxes and the like those that fought could not have kept going. It does take a village . .. But if

Hi all,

I agree and disagree with some of the comments here. I’m relatively young and have been researching my family history for a short time. In that short time, I’ve discovered great achievements and events that my ancestors were apart of, and have joined several lineage socieities (Mayflower, SAR, Winthrop, First Families of CT/RI). I think that some of the eligibility requirement for SAR and DAR are a little relaxed. I joined through a soldier who was in the continential army for two years. Though I understand that the society wants to make sure your ancestor supported the war efforts, I think some combat experience should be a factor for joining, not because your ancestor was a judge at the time.

I think lineage socities offer a lot. I think it helps preserve that family history knowledge for future generations. The information I learned about descending from passengers of the Mayflower, my grandparents had absolutely no idea, even there parents didn’t know. It also serves as a great social gathering of people with similar interests.

If they required combat experience, many — perhaps even most — members wouldn’t be eligible.

I don’t think I can argue with that statement. There is a society, “General Society Sons of the Revolution” where applicants need to show proof that they descend from an ancestor who was in the military and had actual combat experience. I joined the SAR instead (1) because I was still “wet behind the ears” when it came to lineage societies and (2) because it seemed that the SAR was well organized, large, and offered a lot of get togethers, participated in parades, etc.

Are you for or “against” lineage societies? I think there are A LOT of hereditary societies (just look at hereditary.us), many of the appear to be really neat and quite the accomplishment if your eligible, but there are some that seem some what ridiculous.

I don’t have any objection to people getting together as clubs for whatever reason they choose. My objection is mostly to groups that appear to suggest that some folks are better than others merely because of their blind luck in having specific ancestors.

I did not see this episode with Rob Lowe the first time it aired but caught a rerun of it. I was kind of upset by it so I was searching online to see if there were any others who felt this way. Thank you for writing this! On another site, there was a comment left by a person who is also a relative of Rob’s and he said that Rob has other relatives on his mom’s side of the family who fought on the American side. I think it would have been better for Rob Lowe to be accepted into the DAR through THAT relative, Jacob Hepler who actually fought on our side during the American Revolution instead of through his Hessian grandfather who fought AGAINST the colonists. It appears he stayed here after the war because there was nothing much for him to go back to in Germany. So…basically staying here was more self serving. I’m quite baffled about him being labeled a “Patriot” simply because he paid a tax? Didn’t everyone pay taxes?? How does a person go from being an enemy soldier to being in the DAR just for paying a tax that he had to pay? Sorry but in my opinion that does not make him a Patriot. The true Patriots fought FOR and many died FOR this country so I would not put this Hessian soldier in that group. I would feel very differently if he had left the Hessian army and had joined the American troops. There were many German colonists who were patriots and I also read that 35% of the Hessians defected to the Colonial side but apparently Rob’s ancestor was not one of them. Bottom line…he was an enemy soldier. I wonder if he had shot and killed Washington, but later on paid that wonderful tax…if the DAR would be of the same opinion? It seems like the DAR was rather star struck and that probably helped with Rob being welcomed with open arms. They really should have done the story on his Grandfather Hepler who WAS a TRUE Patriot. That would have made far more sense and as far as I’m concerned…would have reflected more favorably on the DAR. Oh…by the way…I DO like Rob Lowe! I just think they went with the wrong ancestor!

Yep, paying a tax alone does seem like a chintzy way into being regarded as a patriot, doesn’t it?

Somehow I missed this article when it first came out, so I am glad you mentioned it in a footnote today. I can sympathize with your feelings. One of my 4xggrandfathers fought on the American side at the Battle of Bunker Hill. The next year he was a Captain in the Connecticut Line at the Battle of Brooklyn where he was knocked unconscious by a wound to the head and left for dead on the battlefield. Fortunately, in the aftermath of the battle he came to and was able to make his way safely back to the American lines. But, unlike your case, the man who tried to kill my CT ancestor could possibly have been another of my 4xggrandfathers, who was a British soldier with the 17th Light Dragoons! As near as I have been able to figure out, both men were fighting over the very same portion of the battlefield on that day.

I find the revolutionary era fascinating. The crucial issue — whether or not to break away from Britain — made for a crisis of conscience that divided friends and families and left the same kind of lasting wounds as the controversy over the Vietnam War did in our own times. Just look at the lingering bitterness shown in some of the comments here. After spending a lot of time reading the accounts of participants on both sides, I now prefer to think of them as “Revolutionaries” and “Royalists,” recognizing that they were all fighting for what they perceived to be the best interests of their country, which is the very essence of what it means to be a patriot.

I’m sure each side was convinced it was right — it’s the way the actions are viewed today that I took issue with,

Me, too.

My mother, who probably had at least half a dozen “Patriot” ancestors, refused to join the DAR because the members of the local chapter acted as if having ancestors who fought in the revolution made them better than everyone else in the neighborhood. She used to say, “I know I can stack my ancestors up against anybody’s and never be ashamed, but I don’t believe in playing that game. It’s not who your *ancestors* were or what *they* did that’s important, but who *you* are and what *you* do with what they have handed down to you.

I have known an awful lot of DAR members, and I seriously wonder how many of them, if they had been living in 1775, without the benefit of 200+ years worth of 20/20 hindsight, would have chosen to support the American side. Their resistance to change and reluctance to accept new ideas struck me as characteristic of those who chose the other side.

There are a lot of very good people in these lineage societies as well, who use their memberships to advance all of our genealogical interests. It’s not my personal “thing” — but I do understand it is for some.

Good points about the service requirements or lack thereof in the different lineage societies I have an ancestor with “associated with” patriots for service in a DAR file. Membership through that person is denied now. We have to remember they were ALL paid though. My Hessian ancestor was paid in coin, but he was also from Kassel which conscripted young men like him into service. Other Hessian principalities were indebted to the British monarch (the protector of the Protestant faith against France and Spain) for coming to their aide in prior European wars. The son of my Hessian ancestor was paid for service in the War of 1812 with land taken from Native Americans. One is his sons was paid for serving for the Union in the Civil War. My paternal ancestor is a patriot that never saw battle and served in a unit that built forts on the frontier. It’s my family’s contribution to our shared history.

It isn’t a matter of whether they were paid — our soldiers today are paid. The issue is whether someone could simply pay and avoid serving, or pay a tax at the end of the war when the outcome was entirely certain and still qualify.