Special investigative reports

It was the worst man-made explosion ever until the Atomic Bomb was dropped. In the blink of an eye, some 1,500 people died. Hundreds more perished afterwards, of injuries or trapped in the flames that spread. Some 9,000 were injured. And essentially nothing — not a live person, not a building, nothing — remained within a two-square-kilometer radius.1

And The Legal Genealogist is willing to bet that only those with Canadian roots know the first thing about it — that horrendous explosion in the harbor of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, on 6 December 1917, 95 years ago yesterday. I for one didn’t know a thing about it until I saw references yesterday to the terrific Canadian Broadcasting Company website, The Halifax Explosion.2

And The Legal Genealogist is willing to bet that only those with Canadian roots know the first thing about it — that horrendous explosion in the harbor of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, on 6 December 1917, 95 years ago yesterday. I for one didn’t know a thing about it until I saw references yesterday to the terrific Canadian Broadcasting Company website, The Halifax Explosion.2

It resulted from the collision of two ships in the harbor. One, the Imo, was an empty relief ship. The other — the Mont-Blanc — was a French munitions ship loaded with nearly 3,000 tons of explosives destined for the war in Europe.3

It wasn’t the initial impact, at 8:45 a.m., that caused the explosion. It was the fire that broke out on the Mont-Blanc.4

What’s particularly intriguing about this case to The Legal Genealogist, of course, is the fact that there was an official Board of Inquiry convened only seven days after the explosion, while Halifax was still reeling under the pressures of thousands of injured, and thousands more left homeless in the winter weather.

The Commission heard testimony, considered evidence, yet in the end, the result didn’t satisfy anybody:

The official enquiry opened less than a week after the explosion. The captain and pilot of the Mont-Blanc and the naval commanding officer were charged with manslaughter and released on bail. Later the charges were dropped, because gross negligence causing death could not be proved against any one of them. In the Nova Scotia District of the Exchequer Court of Canada in April, 1918, the Mont-Blanc was declared solely to blame for the disaster. In May, 1919, on appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada, both ships were judged equally at fault. The Privy Council in London, at that time the ultimate authority, agreed with the Supreme Court’s verdict.5

There isn’t any printed report of that Board of Inquiry that I could find online.6 But it turns out that Boards of Inquiry were and are routine in maritime disasters, and the records created make fascinating reading.

For example, on 15 June 1904, the steamer General Slocum set out into New York waters, having been chartered by St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in New York for an excursion. There were 1,358 passengers on board, 90 percent of them women and children. A fire on board and the subsequent beaching of the ship resulted in the deaths of 955 people — 745 of them children. A special federal commission was appointed to investigate, and issued a 72-page report into the disaster.7

Likewise, just before midnight, 22 January 1906, the steamer Valencia hit a reef near Pachena Point off Vancouver Island. Only 37 men from the ship survived; more than 100 perished, including every woman and child on board. Two investigations resulted, one by the US Marine Inspection Service and the other a special commission reporting to President Theodore Roosevelt. That special commission issued a 53-page report filled with facts and even photographs.8

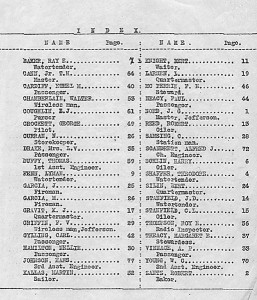

On 17 August 1913, the steamship State of California struck rocks near Alaska and went down in 240 feet of water and sank, killing 35. A Board of Inquiry was convened on to examine the causes of the disaster, and 36 witnesses — from Ray E. Baker, watertender, to Robert Zantz, baker — testified. And digital images of the testimony are available online at the National Archives website.9The first federal legislation involving steamship safety was the Act of 7 July 1838 to “provide better security of the lives of passengers on board of vessels propelled in whole or in part by steam.”10 But it wasn’t until Steamboat Act of 30 August 1852 11 that a federal maritime inspection service began to emerge and any real investigative role began, and not until the Act of 28 February 1871 that the Steamboat Inspection Service was created.12

So in the early years, you’re as likely to find a local report as a federal report. That was the case when the steamship Moselle exploded and sank just east of Cincinnati on 25 April 1838. Some 160 of the roughly 275-300 passengers on board were killed,13, and the local citizens and mayor did their own investigation and produced their own 76-page report.14

Of course, Americans and Canadians weren’t the only ones with special reports on disasters at sea. Some 200 men and boys were on board the steamer Daphne when it was launched on 3 July 1883 in the Glasgow dockyards; they were finishing the internal fittings at the time. Within minutes, it capsized, trapping the workers below decks. The death toll was put at 124. Sir Edward J. Reed was appointed by the Crown to conducted a special inquiry, and produced a 66-page report to the British Parliament, complete with witness testimony.15

And, by the way, maritime disasters aren’t the only things to end up with special reports from special boards. On 12 January 1877, the Ohio General Assembly established a special legislative committee to investigate the causes of the collapse of a railroad bridge over the Ashtabula River on 29 December 1876, killing 92 people. That committee produced a 158-page report, complete with witness testimony.16

Definitely worth inquiring if there were any Boards of Inquiry for any event our ancestors may have been involved with!

SOURCES

- “City of Ruins : The Explosion,” The Halifax Explosion, Canadian Broadcasting Company (http://www.cbc.ca : accessed 6 Dec 2012). ↩

- See generally The Halifax Explosion, Canadian Broadcasting Company (http://www.cbc.ca : accessed 6 Dec 2012). ↩

- Ibid., “City of Ruins : Countdown to Catastrophe.” ↩

- Ibid., “City of Ruins : Collision Course.” ↩

- “The Halifax Explosion,” Maritime Museum of the Atlantic (http://museum.gov.ns.ca/mma : accessed 6 Dec 2012). ↩

- Any Canadian genealogists or historians out there who know of one, let me know! ↩

- Report of the United States Commission of Investigation upon the Disaster to the Steamer “General Slocum” (Washington D.C : U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1904); PDF version, digitized by U.S. Coast Guard, 2003 (http://marinecasualty.com/documents/Slocum.pdf : accessed 6 Dec 2012). ↩

- Wreck of the Steamer Valencia: Report to the President of the Federal Commission of Investigation (Washington, D.C. : U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1906); digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 6 Dec 2012). ↩

- Testimony in the Matter of the loss of the steamship STATE OF CALIFORNIA, 08/22/1913 – 09/01/1913; Casualty file for the STATE OF CALIFORNIA, 1913 – 1913; Casualties and Violations Case Files, compiled 1887 – 1942; Records of the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation, 1774 – 1982; Record Group 41; National Archives – Seattle. ↩

- 5 Stat. 304 (1838). ↩

- 10 Stat. 61 (1852). ↩

- 16 Stat. 440 (1871). ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Moselle (riverboat),” rev. 8 Nov 2012. ↩

- A Report of the Committee Appointed by the Citizens of Cincinnati, April 26, 1838, to Enquire into the Causes of the Explosion of the Moselle… (Cincinnati, Ohio : Alexander Flash, 1838); digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 6 Dec 2012). ↩

- Sir Edward J. Reed, Report on the “Daphne” Disaster (London : Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1883); digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 6 Dec 2012). ↩

- Report of the Joint Committee Concerning the Ashtabula Bridge Disaster, under Joint Resolution of the General Assembly (Columbus, Nevins & Myers, State Printers : 1877); digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 6 Dec 2012). ↩

Addendum: A reader, Joe Callahan, suggests that folks “might also be interested in the sinking of the steamer Atlantic on Lake Erie in 1852, as described on the web site http://www.norwayheritage.com” and he credits Linda Tollefson Therkelsen, “an amazingly capable and generous researcher on Norwegian families,” who led him to it.

I would like to add the explosion of the Steamship Sultana which occurred on 27 April 1865. The ship was bound from Vicksburg to Memphis on the Mississippi River. A history of this event was written by Gene Eric Salecker – “Disaster on the Mississippi – The Sultana Explosion, April 27, 1865” My great-great grand uncle Gideon Harrington perished in that explosion.

That was a big one for sure, Pat, and there was a board of inquiry convened. I didn’t find a copy of the inquiry report online, but would be happy to add a link if anyone knows where it can be found.

Shipindex.org

Since the Cincinatti National Genealogy conference, I have been using shipindex.org. The database crossindexes around the world. People, crews, articles and other sources are easily accessed with links. An orientation video is available, and quite a bit for free. The premier subscription for a minimum fee under ten dollars a month of course will access more data. Since most travel was by ship before 1900, this could be a valuable resource for people to see and learn about the way that families made it over. In addition, there is also the military history perspective. I love looking at the pictures!

Great resource, Candace, thank you for posting!

Thanks for bring the Halifax Explosion to a wider audience, Judy. Yesterday Halifax was in mourning, commemorating the shock and misery of that very sad winter.

I’m glad to have been able to shed light on a stunning tragedy, Brenda. I can’t imagine so very much loss for what was, really, quite a small city at that time.

I would like to add the story of the PS Lady Elgin, a side paddlewheel steamer on the Great Lakes. Chartered for an excursion from Chicago to Milwaukee, she carried about 450 passengers and crew although that was thought that many more were onboard as unregistered passengers. On 7 Sep 1860, a little before midnight, the Lady Elgin was struck below the waterline by the schooner Augusta. Of the estimated 450 on board, only about 100 survived. To this day, it remains the greatest loss of life on the Great Lakes. One side note about the accident. As a result of the accident, the Irish community lost it grip on Milwaukee politics. The leadership mantle was assumed by the Germans and others.

That’s another case for sure, Jeff, and there are scattered references I can find to the fact that there was an investigation into the incident, but I didn’t easily find a copy of the record. If you (or anyone else) knows where it can be found, please post it for reference!

You could start here;

http://www.mpm.edu/education/ladyelgin/explore/

or here;

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PS_Lady_Elgin

Those are good references — but we want the Board of Inquiry report, darn it!

I would like to add the case of the SS Morro Castle, which caught fire at sea in 1934 while her captain lay dead in his cabin and a storm raged around her. The acting captain continued full speed ahead directly into the wind, fanning the flames into an inferno which advanced steadily towards the passengers, who were mostly stranded on the ship’s stern with no way to escape other than to jump overboard into the raging sea. After much loss of life to the fire and the sea, the ship eventually washed up on shore at Asbury Park, New Jersey where it continued to smoulder for days as onlookers gathered to watch. The inquest exposed many shortcomings in the construction, maintenance and training of crew members and resulted in a whole series of new safety regulations being adopted for all passenger ships seeking to sail under US registry. Other legal proceedings also ensued, including at least one criminal trial. None of these succeeded in laying to rest the mysteries surrounding this disaster which continue to be debated.

That’s certainly an appropriate choice. I don’t have an online link to the inquiry that followed. If you do, it’d be great to post it!

I was only able to locate one of the preliminary reports (there ought to be several more somewhere):

http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/002140093

This particular report was issued in support of a proposal to completely overhaul the applicable federal laws following the 1934 Morro Castle disaster and the 1935 sinking of another passenger ship (SS Mohawk) being operated on the same route and by the same steamship line as the Morro Castle. It was somewhat shocking to see so many of the same factors faulted in the General Slocum disaster (extensive use of wood, flammable paints and lacquers, inadequate water pressure, inadequately trained crew, failures of communication and an inability to effectively launch lifeboats) still present thirty years later on a basically brand new and supposedly modern ship, while the inspectors charged with the responsibility for oversight were still being referred to as overworked and underpaid.

More general information is avaioable at:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Morro_Castle_(1930)

http://www.seagirtlighthouse.com/page/The-Morro-Castle.aspx

http://www.museumofnjmh.org/morrocastleanniversary.html

At least two books have been written on the Morro Castle:

Burton, Hal (1973). The Morro Castle: Tragedy at Sea. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-48960-3 (which appears to be Wikipedia’s main source of information relating to the investigations which followed the disaster), and

Hicks, Brian (2006). When the Dancing Stopped: The Real Story of the Morro Castle Disaster and its Deadly Wake. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0743280083 (supposedly containing the results of the author’s examination of additional documents which were subsequently declassified).

Also of interest (SS Mohawk):

http://www.outsideonline.com/adventure-travel/north-america/united-states/new-jersey/The-Ghost-of-Shipwrecks-Future.html

That’s terrific, thanks!

I forgot to mention the most fantastic resource of all when it comes to anything related to New York — the New York Public Library. A quick search shiws multiple hits for materials on both the Morro Castle and the General Slocum:–

http://www.nypl.org/collections

The New York Public Library is a fabulous resource, for sure. Thanks again.