The winter of our content?

Once upon a time, a long long time ago, The Legal Genealogist was a bored and snotty kid. (Enough with the “what do you mean was” comments, already yet.)

To keep me occupied and out of their hair, my parents handed me a set of books written by a fellow named Thomas B. Costain. In four volumes — The Conquering Family,1 The Magnificent Century,2 The Three Edwards,3 and The Last Plantagenets4 — this series traced the royal Plantagenet family from its arrival in England with William the Conquerer in 1066 to the death of Richard III in 1485.

To keep me occupied and out of their hair, my parents handed me a set of books written by a fellow named Thomas B. Costain. In four volumes — The Conquering Family,1 The Magnificent Century,2 The Three Edwards,3 and The Last Plantagenets4 — this series traced the royal Plantagenet family from its arrival in England with William the Conquerer in 1066 to the death of Richard III in 1485.

It’s fabulous reading — something between non-fiction and historical fiction, with powerful storytelling throughout. It’s a real shame that it’s mostly out of print today — or outrageously expensive.5 And if you can find it at a library and take the time to savor it, you’ll come to realize what I realized even as a kid.

Thomas B. Costain didn’t believe for one moment that Richard III, England’s last Plantagenet king, deserved the bad rap he’d gotten in history. He didn’t believe Richard was a bad king and — above all else — didn’t believe for one minute that Richard killed his nephews, the princes in the tower.

It’s almost as if he wrote the entire series to prove that one point: Richard wouldn’t have done it. And I for one came away feeling that if I’d been on the historical jury, I’d have voted for a verdict of not guilty or, at a minimum, not proved.

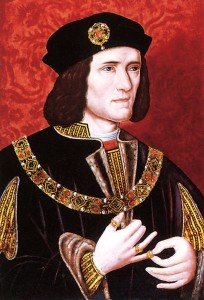

And it’s that sort of thing that makes Richard III such a fascinating historical figure. He ruled for only two years, yet his decision to set aside the sons of his brother Edward IV and take the throne himself is one of the most hotly debated issues of history.

Was there reason to believe the boys illegitimate? Did Richard murder them, the princes in the tower? Did that justify the overthrow of that King by his successor, Henry VII, whose Tudor family came to power when Richard died in that last battle at Bosworth Field?

Was he, as he is often described, an ambitious hunchback with a withered arm who would stop at nothing to secure his own power?

History, they say, is written by the victors and Richard’s history as we know it today was written in works like Shakespeare’s Richard III. Shakespeare, you remember, was writing at the time of, and largely with the hopes of being paid by the likes of, Elizabeth I, last of the Tudor monarchs. If people know anything about Richard III today, they’re likely to remember only his self-description from Shakespeare’s pen:

I, that am rudely stamped …

…curtailed of this fair proportion,

Cheated of feature by dissembling nature,

Deformed, unfinished, sent before my time

Into this breathing world, scarce half made up,

And that so lamely and unfashionable

That dogs bark at me as I halt by them…6

But maybe, just maybe, the start of a new chapter in Richard’s history is being written. And it’s being written, in part, by DNA. Because late in the afternoon tomorrow, Eastern standard time, we may well all know something more about Richard III than we do today.

Because, by late tomorrow afternoon here in the eastern US (by 10 p.m. in London, England), we should know whether remains found late last summer under a parking lot in England are those of Richard III. And it’s DNA that could make the answer to that question definitive. (UPDATE: There’s a press conference we MAY be able to see from the US at 10 a.m. London time — 5 a.m. Eastern — so by the time we get up tomorrow…)

The remains were found in an excavation of what is believed to have been Grey Friars friary, a small Franciscan church where Richard’s body was taken after the battle where he died.7 Though some reports were that Richard was buried there, the official British history of the monarchy reports even today: “Buried without a monument in Leicester, Richard’s bones were scattered during the English Reformation.”8

An examination of the remains was consistent with what’s known of Richard: the person buried, like Richard, had a deformation of the spine; the person buried had wounds consistent with battle wounds; and a barbed metal arrowhead was found where it would have been embedded in the person’s back.9

But wounds and physical characteristics “consistent with” what was known of Richard doesn’t mean the person buried there was Richard. More will be needed to say yea or nay on that question. And there is more… there is Michael Ibsen.

Michael Ibsen is a 55-year-old Canadian-born furniture maker now living in London.10 And he is the last known living descendant of Richard III’s mother in a direct matrilineal line of descent:

Anne of York, Duchess of Exeter, 1439-1476, mother of

Anne St Leger, 1476-1526, mother of

Catherine Manners, c.1500-?, mother of

Barbara Constable, c.1525-?, mother of

Margaret Babthorpe, c.1550-1628, mother of

Barbara Cholmley, c.1580-1618, mother of

Barbara Belasyse, 1609-1641, mother of

Barbara Slingsby, c.1637-?, mother of

Barbara Talbot, 1665-1763, mother of

Barbara Yelverton, 1687-?, mother of

Barbara Calthorpe, c.1716-1782, mother of

Barbara Gough-Calthorp, 1744-1826, mother of

Anne Spooner, 1780-1873, mother of

Charlotte Vansittart Neale, 1817-1891, mother of

Charlotte Vansittart Frere, 1846-1917(?), mother of

Muriel Stokes, 1884-1961, mother of

Joy Brown (Ibsen), 1926-2008, mother of

Michael Ibsen11

Remember that there is a type of DNA called mitochondrial DNA, or mtDNA, that passes from a mother to all of her children but that only her daughters can pass on.12 So all of Cecily Neville’s children would have her mtDNA — Richard III included. And the skeletal remains were tested for mtDNA.

Cecily’s daughter Anne would also have her mtDNA, and that mtDNA was passed down, with few if any changes, through all those generations until Joy Ibsen passed it to her son Michael. And Michael agreed to be tested as well.

Of course there’s no guarantee that there wasn’t a non-paternity event sometime in the more than 500 years since Cecily Neville’s children were born. (Correction: A non-paternity event isn’t an issue here. We’re talking maternity, not paternity. So the risk is that there might have been an undocumented adoption, not that there might have been a non-paternity event.) And if there was, all bets are off.

But tomorrow afternoon, we may find out. Because starting at 4 p.m. EST (9 p.m. in London), Britain’s BBC Channel 4 will be broadcasting the results of all of the analyses and lab work — of the dig, the forensics… and the DNA. We can’t watch the program live here in the U.S., but …

All I can say is… here’s one snotty kid who’s going to have all available news feeds pumping through to my work computer starting at 4 p.m. tomorrow.

And one who’s really rooting for a DNA match to begin a new chapter in the history of Richard III.

SOURCES

- Thomas B. Costain, The Conquering Family (Garden City, N.Y. : Doubleday, 1949). ↩

- Thomas B. Costain, The Magnificent Century (Garden City, N.Y. : Doubleday, 1951). ↩

- Thomas B. Costain, The Three Edwards (Garden City, N.Y. : Doubleday, 1958). ↩

- Thomas B. Costain, The Last Plantagenets (Garden City, N.Y. : Doubleday, 1962). ↩

- The set was published once in paperback, but is available today only in the occasional hardback or for the Kindle — with the price set by the publisher at $18 to $30 per volume. Ouch. ↩

- William Shakespeare, Richard III, Act I, scene I; Project Gutenberg HTML version (http://www.gutenberg.org : accessed 2 Feb 2013). ↩

- See generally “Human remains found in search for King Richard III at Leicester car park,” This is Leicester, online, posted 12 Sep 2012 (http://www.thisisleicestershire.co.uk/ : accessed 2 Feb 2013). ↩

- “Richard III,” The British Monarchy, History of the Monarchy (http://www.royal.gov.uk/historyofthemonarchy : accessed 2 Feb 2013). ↩

- “Skeleton with ‘battle injuries’ found by Richard III dig team in Leicester,” This is Leicester, online, posted 12 Sep 2012 (http://www.thisisleicestershire.co.uk/ : accessed 2 Feb 2013). ↩

- Laura Dixon and Lucy Bannerman, “DNA test may solve 500-year mystery of last Plantagenet’s burial,” The Times, posted 2 Jan 2013 (http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/ : accessed 2 Feb 2013). ↩

- Table 1, Plantagenet DNA(http://plantagenetdna.webs.com/ : accessed 2 Feb 2013). ↩

- See ISOGG Wiki (http://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Mitochondrial DNA,” rev. 30 Jul 2010. ↩

another Ricardian!

Oh yeah, that’s me all right. I can’t wait to see what tomorrow brings.

I am just as curious as you. I know I’ll be staying up to 11 PM tomorrow night to watch it live here in the Netherlands.

Next month, I’ll be in London to attend Who Do You Think You Are Live (the biggest genealogy event in the world). One of the workshops I signed up for is a lecture about these Richard III discoveries by the scientists who worked on the case. I was so excited to see that on the schedule!

By the way, the good thing about mitochondrial DNA is that is is NOT affected by a non-paternity event, just by non-maternity events (aka undocumented adoptions). And for obvious reasons these are a lot rarer… So the comparison between Michael Ibsen’s DNA and the skeleton’s should provide us with a clear answer.

I wish I could go to WDYTYA in London, darn it. And of course you’re right about the non-maternity, not non-paternity. I knew there was something bothering me about that when I wrote it and my brain was too fried from a nine-year-old’s birthday party to figure it out. The only concern in a maternal line would be an undocumented adoption.

I’ll write a blog post about the trip!

I’ll look forward to reading it, Yvette!

I can hardly wait – not because I’m a Ricardian like several of you – but because I absolutely love mysteries, especially historical mysteries, and most especially scientific historical mysteries! (Yup, I love genealogy!) I’ll be tuning in as well to find out the results.

This sort of history mystery is fun for all of us, I would hope. Except those who’ll be too hung over from the Superbowl to care!

Love the fact of DNA playing the role, should we say, it was designed for! How totally awesome bringing truth to history. I have had some experience of this sort with one of my lines being linked to Niall of the Nine Hostages. Now, if I could only prove my 2 DNA cousin matches in England and 1 in Australia.

It really is wonderful stuff, isn’t it? It would be soooo cool to get this as a match. As for figuring out your lines, tell me about it — you and I can’t even figure out how you match my Buchanan cousin with atDNA!

I remember reading this Costain series as well! Thanks for the reminder; I’ll have to see if they’re in storage!

Glad to nudge you in that direction, Ann!

Like many of the comments here, I too find this absolutely fascinating. I have all 4 copies of Thomas B. Costain’s “Pageant of England” series, stared reading them about 6 weeks ago, currently reading the 3rd book, and find them informative and easy to read. I found them available at various independent book sellers–via Google on the internet. I would venture to say all of us with genealogical DNA of British ancestry would love to have ours compared to this one recorded descendant of the Plantagenet line.

Nice to hear from another Costain fan, Sheila! And oh yeah… wouldn’t it be nice to have one line, just one line, as well researched and documented as this???