Next in an occasional series on copyrights for genealogists.

Reader Lee was confused about his right to use images of articles and other contents of newspapers from his state that he was accessing through microfilmed copies at his local library.

He explained that the state’s library and archives tried to microfilm all of the state’s newspapers in the 1960s and 1970s, and that the “reels indicate that the state filmed them and lists the date, but … do not contain a copyright notice.”

He explained that the state’s library and archives tried to microfilm all of the state’s newspapers in the 1960s and 1970s, and that the “reels indicate that the state filmed them and lists the date, but … do not contain a copyright notice.”

Today, the films are “at local libraries around the state and are used regularly for historical research.”

So, he asked:

• “Does the state library and archives own a copyright on these microfilmed copies of the newspaper?”

• “Which date counts for copyright? The date the paper was published or the date the state microfilmed it?”

Good questions.

With relatively easy answers.

No, the state library and archives doesn’t have a copyright on the microfilmed copies. In fact, a microfilmer isn’t ever going to qualify for a copyright under American law in anything the microfilmer didn’t add to the originals it was copying.

The concept here is a fundamental one of American copyright law: you can only get a copyright on material that is original. The statute couldn’t be clearer: “Copyright protection subsists, in accordance with this title, in original works of authorship…”1

Now what exactly has to be shown for something to be considered original has been a hot topic for the courts to decide. But two court decisions have pretty well answered the question.

First, the U.S. Supreme Court decided a case involving a telephone directory that had been produced by a local telephone company and then copied by another company that specialized in publishing regional phone books. And there, in Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., the Court said:

The sine qua non of copyright is originality. To qualify for copyright protection, a work must be original to the author. … Original, as the term is used in copyright, means only that the work was independently created by the author (as opposed to copied from other works), and that it possesses at least some minimal degree of creativity. …

Originality is a constitutional requirement.2

The Feist Court went on to explain that it didn’t matter how much effort a company put into compiling its information — how much “sweat of the brow” work it did. If it wasn’t original, it wasn’t copyrightable.

Now some people tried to argue that the Feist case only applied to factual compilations, since that was the type of publication involved there. But some years later, a federal trial court in New York decided a case involving artistic works and came to the same conclusion.

In Bridgeman Art Library v. Corel Corp., the issue involved photographs of art works from European museums. All of the art works themselves were out of copyright, but the company that produced the photographs claimed a copyright in the photos. The court rejected the claim:

In this case, plaintiff by its own admission has labored to create “slavish copies” of public domain works of art. While it may be assumed that this required both skill and effort, there was no spark of originality — indeed, the point of the exercise was to reproduce the underlying works with absolute fidelity. Copyright is not available in these circumstances.3

What counts, then, for copyright purposes is not the microfilming — that’s the same sort of slavish copying that simply doesn’t qualify for copyright protection. What counts is whether the original is still under copyright protection. So the answer to the second question is, the copyright is measured from the original publication of the newspaper, not the date on which it was microfilmed.

Since Lee was using only newspapers published before 1923 — and since everything published in the United States before 1923 is now out of copyright and in the public domain4 — he has nothing to worry about.

So… does that mean there are never restrictions on our ability to use microfilm?

No, because there are circumstances where the content is protected one way or another:

• The microfilm may be a licensed copy of material that is still copyright-protected. An example would be a microfilm of a newspaper published in 1990. (Copyright for a work of corporate authorship of this type is 95 years from the date of publication.5)

• The microfilm might be of an unpublished manuscript of an author who died less than 70 years ago. (Copyright for an unpublished work is the life of the author plus 70 years.6)

• The microfilm might be of an unpublished manuscript created by an author in 1900 but whose death date is unknown. (Copyright lasts for 120 years from the date of creation in that case.7)

• The microfilm might be made available only under specific terms and conditions — imposing contract law, not copyright law8 — that we have to abide by.

But as to the typical newspaper microfilm… a copy of an original has only the same protection as the original, and if it’s out of copyright, it’s out of copyright. Period.

SOURCES

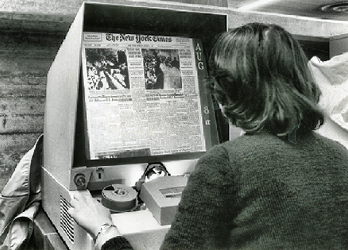

Image: University of Haifa Library, Wikimedia Commons

- “Subject matter of copyright: In general,” 17 U.S.C. §102(a). ↩

- Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 U.S. 340, 345-346 (1991). ↩

- Bridgeman Art Library v. Corel Corp., 36 F. Supp. 2d 191, 197 (S.D.N.Y. 1999). ↩

- See Peter B. Hirtle, “Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States,” Cornell Copyright Center (http://copyright.cornell.edu/resources/publicdomain.cfm : accessed 13 July 2014). ↩

- See ibid. ↩

- See ibid. ↩

- See ibid. ↩

- See generally Judy G. Russell, “A terms of use intro,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 27 Apr 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 13 July 2014). ↩

This was most helpful. How do copyrights and other protections apply to images found on the internet?

A digital original is still an original, so EVERYTHING on the Internet should be assumed to be copyright protected until and unless you determine otherwise.

Explain how “A digital original is still an original”

when digital is a copy/duplication of the original

Think digital photography. There never is anything BUT a digital original.

Couldn’t the logic of Bridgeman Art Library v. Corel Corp. be applied to tombstone photographs?

In theory, yes, except for the additional language of the Bridgeman case: “There is little doubt that many photographs, probably the overwhelming majority, reflect at least the modest amount of originality required for copyright protection. ‘Elements of originality . . . may include posing the subjects, lighting, angle, selection of film and camera, evoking the desired expression, and almost any other variant involved.’ But ‘slavish copying,’ although doubtless requiring technical skill and effort, does not qualify.”

Judy,

I want to let you know that your blog post is listed in today’s Fab Finds post at http://janasgenealogyandfamilyhistory.blogspot.com/2014/07/follow-friday-fab-finds-for-july-18-2014.html

Have a wonderful weekend!

Thanks so much, Jana!

Thank you so much for sharing this information. I can hardly wait for your seminar to be held in Portland, OR this fall.

I’m looking forward to that Portland trip too! (I’ll have a brand new baby grand niece to visit as well!)

What about screen captures of Proquest articles for newspaper articles before 1923? Does the fact that these articles are word searchable (OCR-optical character recognition) imply more than sweat-of-the-brow effort. The text is not copyrightable but is the image of the text copyrightable?

It’s not copyright law that affects how we can use pre-1923 articles on ProQuest products. It’s contract law. What we can and can’t do with the content is governed by the terms of use (or terms of service) of the individual website.

Thank you.