Next in an occasional series on copyright.

It’s impossible to be a genealogist — or at least a good genealogist — without paying attention to the family Bible.

Repository of so many facts (and, often, so many fancies) of family history, the family Bible is a source of great importance whenever and wherever it can be found.

Repository of so many facts (and, often, so many fancies) of family history, the family Bible is a source of great importance whenever and wherever it can be found.

And, occasionally, as we sit there ready, willing and able to write up some chapter of family history, we find a verse in the scriptures that we want to quote, sometimes even quote at length.

Can we?

Or do we have to worry about that niggling nagging issue called copyright?

The answer?

(You saw this one coming a mile away, didn’t you?)

It depends.

Now you might be sitting there wondering how it can possibly be an issue. After all, we all know that anything published in the United States before 1923 is now officially out of copyright and in the public domain.1 That means there is no copyright restriction on it of any kind and you are free to use it in any way you’d like.2 And surely the Bible was published in the United States before 1923!

Not to mention the fact that, even for material previously unpublished, the original authors of any of the books of the Bible have certainly been dead for more than 70 years, putting that material into the public domain as well.3

Except for one minor little detail.

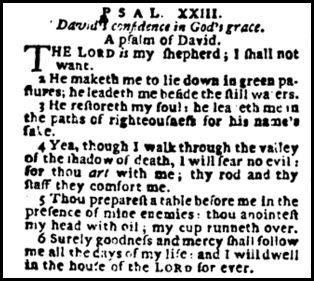

The original works that are today the Bible were written in Hebrew. Or Aramaic. Or Greek. Most assuredly not in English. Which means that every copy of every Bible that I might be able to read today4 is a translation.

And therein lies the rub.

Because translations are regarded as the kind of works that, in and of themselves, are capable of being copyrighted.5 And a whole bunch of modern translations of the Bible are in fact copyrighted.

Examples of currently-copyrighted translated versions of the Bible include the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1946, 1952, and 1971 by the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America; the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989 by the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America; the New International Version®, copyright 1973, 1978, 1984, and 2011 by Biblica, Inc.; the New Living Translation, copyright 1996, 2004, 2007, and 2013 by Tyndale House Foundation, Carol Stream, Illinois; and the New King James Version®, copyright 1982 by Thomas Nelson Publishers.

In other words, a whole bunch of the standard versions, including the ones we probably have at home.

Including one that surprised even The Legal Genealogist.

The King James Version.

The original version.

Translated in England between 1604 and 1611.

Of course, it’s only protected in England, and only because of a truly unique set of monopolies and grants that are not exactly the same as copyrights and are set to expire in 2039.6

So… can we use these translations? Or are we going to get into copyright trouble?

For the most part, any use we as genealogists might make of any of these translations is perfectly fine. Even the publishers themselves realize that people are going to quote the Bible, they’re going to quote the one they use most frequently, and they’re going to drive the publishers batty if we had to have permission for every little use. So most publishers, on their websites, give blanket permission for non-commercial use up to some limit:

• Revised Standard Version and New Revised Standard Version, “less than an entire book of the Bible, and less than 500 verses (total), and less than 50 percent of the total number of words in the work in which they are quoted (and no) changes are made to the text” and attribution.7

• New International Version, for individuals, “for personal, noncommercial use, … up to and inclusive of 50 verses, … provided the verses quoted do not amount to a complete book of the Bible nor do the verses quoted account for five percent (5%) or more of the total text of the work in which they are quoted” and for churches or and nonprofit educational institutions, “for personal, noncommercial use, … up to and inclusive of 500 verses, … provided the verses quoted do not amount to a complete book of the Bible nor do the verses quoted account for twenty-five percent (25%) or more of the total text of the work in which they are quoted” and with attribution.8

• New King James Version, in any form (written, visual, electronic, or audio) up to five hundred (500) verses or less without written permission, as long as the Scripture does not make up more than 25% of the total text in the work and the Scripture is not being quoted in commentary or another Biblical reference work, and with attribution.9

• The King James Version, “a maximum of five hundred (500) verses for liturgical and non-commercial educational use, provided that the verses quoted neither amount to a complete book of the Bible nor represent 25 per cent or more of the total text of the work in which they are quoted,” and with attribution.10

So, yes, no, and maybe.

But, for the kind of use we as genealogists might make of it, I’d feel perfectly confident that I could go ahead and use that verse or set of verses anyway.

And be forgiven even if I was wrong.

SOURCES

- See Peter B. Hirtle, “Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States,” Cornell Copyright Center (http://copyright.cornell.edu/resources/publicdomain.cfm : accessed 11 Dec 2014). ↩

- See generally “Where is the public domain?,” Frequently Asked Questions: Definitions, U.S. Copyright Office (http://www.copyright.gov : accessed 11 Dec 2014). ↩

- See Hirtle, “Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States.” ↩

- I won’t speak for you. You, after all, might be fluent in Hebrew and Aramaic and Greek. I have enough trouble with English. ↩

- See U.S. Copyright Office, Circular 14: Copyright in Derivative Works and Compilations, PDF version at 2 (http://www.copyright.gov : accessed 11 Dec 2014). And see Laura N. Gasaway, “Copyright in Translations,” Copyright Corner (Nov. 2004) (http://www.unc.edu/~unclng/copy-corner73.htm : accessed 11 Dec 2014). ↩

- See Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “King James Version,” rev. 11 Dec 2014. ↩

- NRSV, Licensing/Permissions (http://www.nrsv.net/contact/licensing-permissions/ : accessed 11 Dec 2014). ↩

- Biblica, “Permitted noncommercial uses,” Terms of Use (http://www.biblica.com : accessed 11 Dec 2014). ↩

- Harper Collins Christian Publishing, Permissions (http://www.harpercollinschristian.com/permissions/ : accessed 11 Dec 2014). ↩

- Cambridge University Press, “King James Version,” Bibles: Rights and Permissions (http://www.cambridge.org/bibles/about/rights-and-permissions/ : accessed 11 Dec 2014). ↩

Judy,

I want to let you know that two of your blog posts are listed in today’s Fab Finds post at http://janasgenealogyandfamilyhistory.blogspot.com/2014/12/follow-friday-fab-finds-for-december-12.html

Have a great weekend!

Thanks so much, Jana!

So, if a quote from a modern translation of the Bible which is in copyright, wouldn’t it be a good idea to contact the publisher and ask about their policy for permission of use and fees when quoted in a published work? I have contacted publishers of Hymnals before who owned the copyright of an old hymn that is in the public domain because it was in their published collection, and they quoted permission & fees for use. Does this sound correct to you?

Not exactly, Debra. If something is in the public domain, then it’s in the public domain, no matter who chooses to republish it. You don’t need permission from the republisher and you don’t need to pay fees to the republisher as to anything that is in the public domain. The copyright held by a republisher is ONLY as to the new material added by the republisher; the republisher can’t get a new copyright on the public domain material by itself. (It might get a copyright on the selection of materials and the way they’re presented, but there’s no way the republisher can stop you from using another older version of the same piece if it is in fact out of copyright.)

Hi Judy:

Sorry for the delay in commenting on this, but I wanted to confirm with some knowledgeable sources in the UK that Wikipedia is partially wrong as far as the King James (Authorized Version) of the Bible is concerned. It is not protected by copyright in the United Kingdom (not just in England); it is in the public domain. But reproduction and distribution is protected by royal prerogative. That means that the formerly-perpetual copyrights that will expire in 2039 do not include the Authorized Version or the Book of Common Prayer. They will remain subject to royal printing privilege and/or royal patents. (Little known fact: as far as Parliament knows, the only two works still subject to perpetual copyright under the 1775 Universities Act and whose copyright will expire in 2039 are Clarendon’s History of Rebellion and Civil War in Ireland and the Life of Edward Earl of Clarendon.)

Wikipedia has been corrected.

Thanks so much for joining in the discussion on this, Peter. So the King James Version stays protected under these royal patents. Oy.

It is important to know what version of the Bible is being quoted. Not all translations are created equal and there can be significant differences between how particular verses are translated. Many versions have topic statements at the top of each page. These are not part of the text and provide, in effect, an interpretation of the text. One importance of family Bibles is not just the family records written in them, but the publication information. This lets us discover what text great-great-grandfather was reading and what interpretation the publisher provided, not only in topic statements, but in introductions to books, footnotes, maps, etc.

Absolutely — every single fact in context can be important.

But when do the US copyright privileges expire? I’d love to see a chart.

There’s one linked in just about every copyright post I write: Copyright Term and the Public Domain, at the Cornell Copyright Center.